Space in Space

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #165. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What does digital grass feel like?

———

Mars First Logistics might be the first truly successful open world game I’ve ever played.

I’m not an open world hater. I remain an Assassin’s Creed girlie no matter how bloated they get. But almost every open world game struggles with the point A to point B journey. With so much space, it becomes a huge part of the game, punctuated only by some sort of hostile wolf or bandit, or maybe a resource to hit A over as you pass by like the world’s least complicated rhythm game.

And yes, sometimes, games manage to make that thematically relevant or narratively fitting, or at least plain more interesting than usual. I’ve been effusive over the surprises and tiny details hidden in Tears of the Kingdom and I do think that game would be much worse without stumbling into some incredibly picturesque lake that has no relevance to the plot or the 25 side activities. But that still must fight with the trade-off of constantly running over blank grassy meadows for several uninterrupted minutes in a game that’s already unapproachably long.

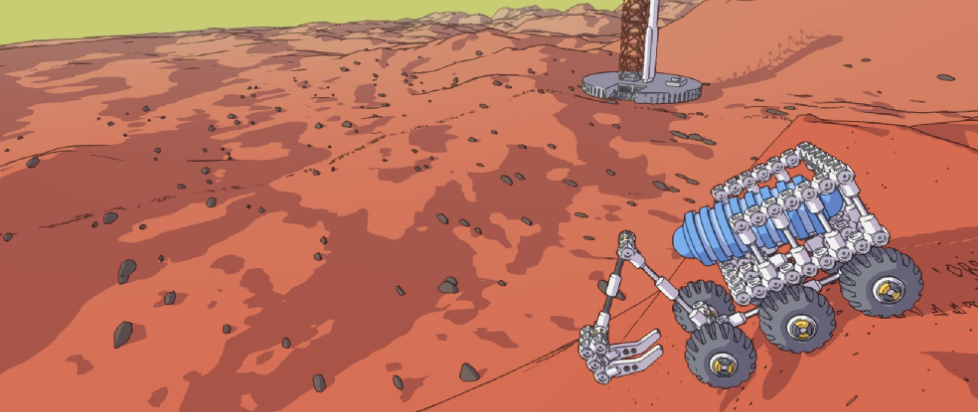

Mars First Logistics being about delivery, moving through the open world becomes something very deliberate, rather than feeling like an accident with, at best, an improvised solution. Building lopsided little robots and coaxing them across the Martian desert wouldn’t work if that desert wasn’t wide and full of expertly placed sand dunes ready to topple over your precariously balanced creations. There are no horses here to speed things along, it’s just you and whatever monstrous contraption you’re trying to get up a 90-degree cliff face.

There are undoubtedly other games where moving through the world is itself all or part of the challenge in this way. But in Mars First Logistics it’s not only gameplay but also tone. It is deeply slapstick to create a sweet little bug-like robotic guy, get immediately attached to them, have them oh-so-carefully pick up a pallet of apples, and then set off with all the optimism in the world only to eat shit on some kind of small but inopportune dust pile. (It is even funnier to do this in co-op, particularly if you are, like me, playing with an actual engineer who can figure out a real solution while you haphazardly throw things around.)

And you will drop those apples. The delivery start- and end-points are always carefully placed on either side of an obstacle, although that might not be obvious at first. If there’s a ravine, you’ll see it, but uneven terrain has a habit of being more disruptive than it looks. The low gravity doesn’t help, but I suspect that everything is very floaty on purpose, from construction to controls. You certainly could scout it out and take into account while building, but it’s a lot more likely that it will surprise you – and besides, it’s a lot more fun to tackle through trial and error.

The game makes this easy, resetting either your vehicle or the challenge entirely are both straightforward and unpunished. You weren’t supposed to get it right first time. You were supposed to do a sick flip and scatter apples everywhere. Mars First Logistics doesn’t only make failure a possibility, it revels in it.

That does come from both the building mechanics and the cargo itself, too. This game wouldn’t work without the trinity of experimental engineering, wacky tasks and interesting distance to cover. But while those are highlighted by the marketing and store descriptions of the game, the influence of the world itself goes unspoken.

Maybe we’re so used to treating open spaces in games as incidental, as there for the sake of size or for debating over “density” whenever a new advertisement comes out about just how big the latest Bethesda game will be. But there’s more to how these worlds work than that. There are no collectables or crafting materials hiding out among Mars’ terrain, but there doesn’t need to be. It’s the space itself that’s important.

———

Jay Castello is a freelance writer covering games and internet culture. If they’re not down a research rabbit hole you’ll probably find them taking bad photographs in the woods.