Composing the World of Ultraviolet Grasslands and the Black City

This feature is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #163. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

This series of articles is made possible through the generous sponsorship of Exalted Funeral. While Exalted Funeral puts us in touch with our subjects, they have no input or approval in the final story.

Ultraviolet Grasslands (UVG) is a tabletop RPG that portrays a world composed by music. To get more genre-specific, it’s described by creator Luka Rejec in the introduction of his game book as, “a fantascience roleplaying adventure setting designed to take the [player characters] on a long strange trip across a mythic steppe filled with remnants of space and time and distorted riffs.”

Rejec’s world is suffused with mind-expanding, psychedelic heavy metal and is also inspired by “the Dying Earth genre, and Oregon Trail games.” The author is no stranger to designing worlds that are inspired by music, but what makes UVG, and especially this second edition of the RPG titled Ultraviolet Grasslands and the Black City, unique to Rejec’s design ethos is how holistic and granular the details of his vision are.

In a 2018 interview by the blog Dungeons & Possums about his work on similarly musical Frostbitten & Mutilated, Rejec succinctly explains his RPG book design philosophy. He states that his priority is to treat game books as “tools, not novels,” and that the purpose of the aesthetics should be to make players have more fun using such tools. The worst pratfall of game book design in his opinion is when the art and layout are inconsistent. Examples of this could be “Metal fonts in a game about kind mushroom people. Poor alignment. Inconsistent sizes. Lack of white space for notes and marginalia.” One look at UVG 2E and the reader can see that Rejec practices what he preaches wholeheartedly – the game’s focus is on traveling and exploring vast and strange horizons, and one of the biggest updates to 2E is to emphasize the surreal and prismatic-colored setting.

When I asked what the biggest changes between 1E and 2E were, Rejec responded that chiefly the hardcover reissue is 252 pages instead of 200, “so the art is bigger and some sections are expanded: bestiary, vehicles, mounts, options for those” but that he and his team have “rearranged the chapters to put the setting front and center, then a module on the caravan and travel rules so they can be used with the old school [OSR] or d20 system of the players’ choice”. A particularly surprising change was that “the [game’s] ruleset itself has been simplified to a one-page reference and mostly moved out of the way.” This is quite a departure (if you’ll forgive the pun) from 1E, which features Rejec’s custom system that he playfully refers to as “the full rules formerly known as [SEACAT]”, now styled as the Synthetic Dream Machine. The updated ruleset will now be offered “in a separate 32-page document (and zine) that’s easy to reference, while the book focuses much more on the things the referee needs to run a game in the UVG.” Rejec is aware this will likely ruffle the feathers of some previous players but is confident that this was the best decision to hone the focus of the core guide.

What impresses me the most when perusing UVG 2E is that it really gets at how important paratextuality is – the linkage between the different aspects of the text and broader socio-historical moments it references via its artistic influences. Especially for a game that’s meant to evoke the spirit of psychedelic heavy metal and the feelings of wanderlust it can inspire (both physically and mentally), having a text that mirrors the free-flowing yet epic sensibility of that musical era in every design element is key.

From the bold fonts, to the ample yet balanced margins, to the revised referee screen, to a grand map of the Grasslands that is several pages long and left purposefully incomplete so that players can fill it with their journey’s discoveries and more, to even the book’s endpapers. Everything has been given due consideration with regard to giving fuel to players’ far-out speculations. Rejec commented that “I’ve also figured out a few stylistic elements to help tie it a bit more into the next setting book: Our Golden Age, which is a sort of [blank]-quel to [UVG] and reveals some aspects of the more… ahem… civilized realms.”

As a brief aside, the setting book is written in the style of “a panegyric to the lords of the realm, which puts the players in the position of reading very blatant propaganda for a system that has quite terrible downsides.” A perfect way to thread a theme of “the thin line between a utopia and a dystopia” throughout a guide that players will be referring to and interpreting often. The godlike lords of the realm also stratify the players via color coding, which he likens to the Paranoia RPG if it was “a whole garden of Eden.” This styling is a smart touch for an RPG with strong visual design elements.

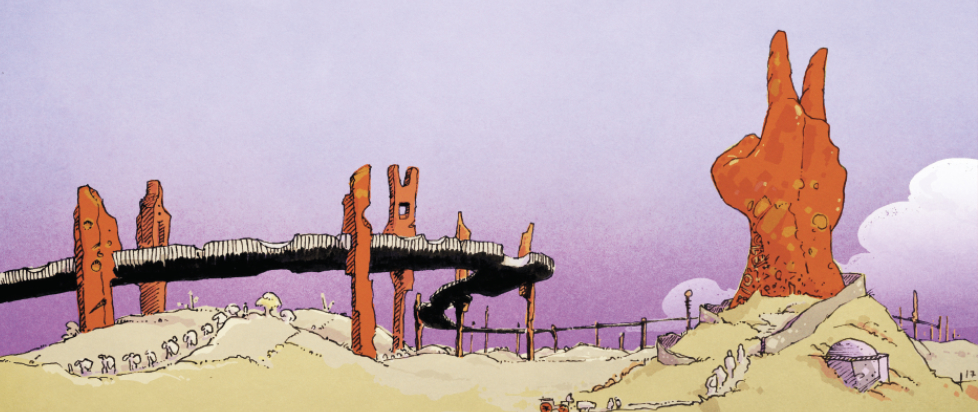

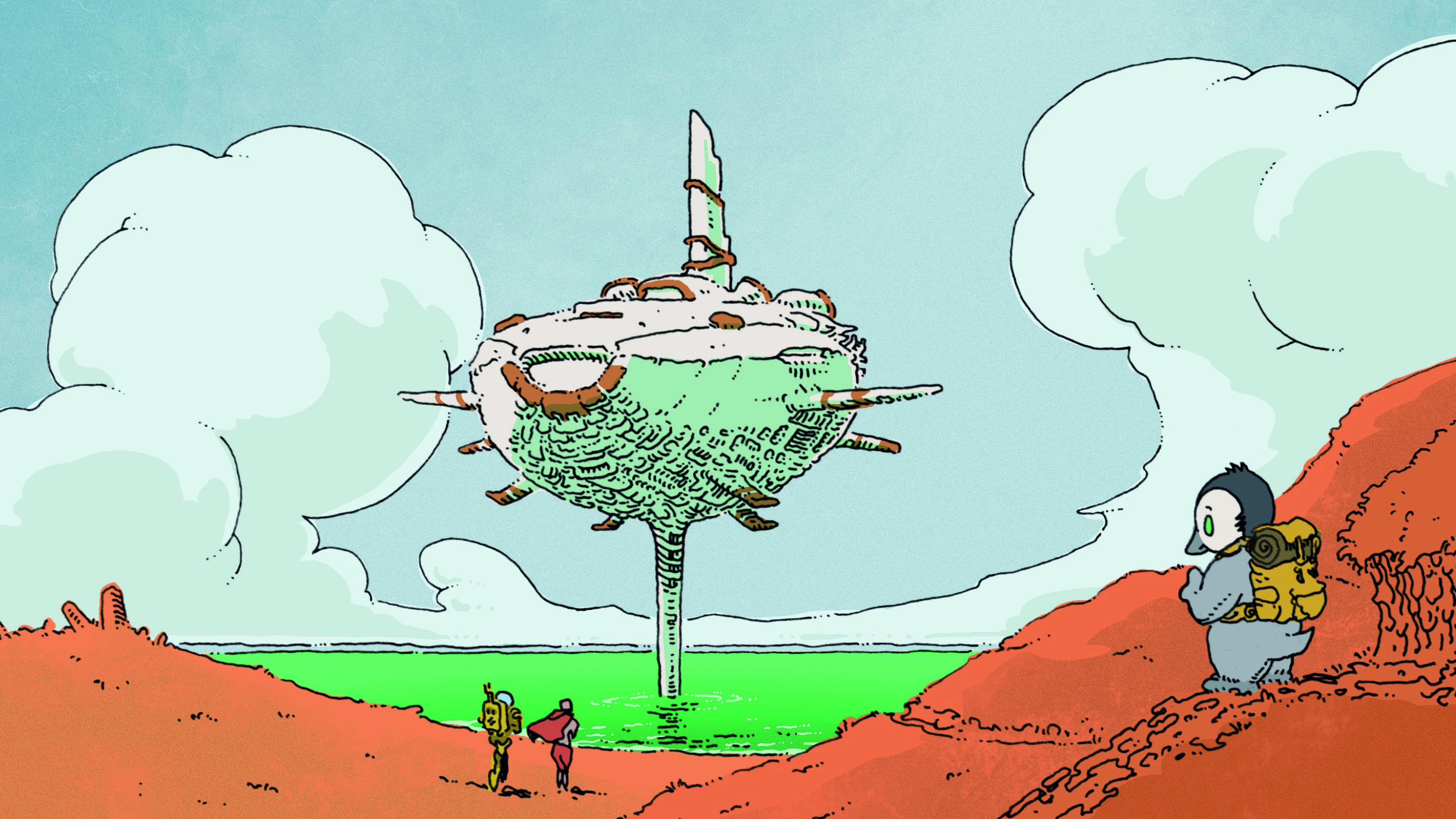

Of these elements, Rejec is the most proud of his artwork for the book, and rightly so. Giving the art more space in the book, which features a beautiful economy of line reminiscent of artists like Hergé, Aubrey Beardsley, Uderzo (just to name a few) and vibrant colors that bring to mind Caza or “the loose style of Hugo Pratt and the watercolors of Milo Manara.” Although I’m citing certain artists Rejec has discussed with me here, his style philosophy is not restricted to just these individuals.

Psychedelic metal arose out of a serendipitous fusion of various music stylings and spontaneous yet passionate experimentations with instrumentation, as well as idiosyncratic themes capturing the turmoil of the changing times. Similar to the confluence of forces that brought about such an innovative genre, Rejec’s creative influences aren’t a one-to-one ratio. I actually made a rather hasty assumption upon first viewing Rejec’s illustrations that they were primarily inspired by Moebius’ comic art. “I don’t draw a hard and fast line, saying this inspired me and this didn’t. Everything is an inspiration and useful to developing a [personal] style and aesthetic,” he responded, when I brought this assumption into my questioning about what specific artists or aesthetic movements fed into his unique visions for UVG. He draws not just on pop art, but fine artists like Picasso, Escher, Dali, Magritte and “the mechanorganic work of H.R. Giger,” who all blur the lines between popular and avant-garde styles. He enjoys visiting art fairs and looks forward to visiting Miami’s Art Basel someday. But one of his greatest motivators for finding new visual expressions is to study nature and challenge himself to capture a little of its majesty.

“There’s something astonishing and humbling to the interplay of forms and lights,” he explained, drawing on the example of recently experiencing cherry blossom season in South Korea – “the way morning light shines through an avenue of trees completely covered in white flowers is indescribable. There’s this numinous quality to it, as though the blossoms are glowing with an inner light, and when you’re walking through everything feels like it’s bathed in soft scattered light. Crazy. And, I cannot capture it at all. I’ve tried with photos, ink, screen. Nope. Not even close.” But in spite of admitting that there are some qualities that’ll never be fully reproduced in his art, he’s always game to try once more.

Relating to this reverence towards nature and ineffable essence, something that struck me about UVG’s system is its commitment to being open-ended and unrepeatable. In 2E’s introduction, Rejec tells readers and potential players point blank that UVG “is designed to resist repetition and canon” and that they are encouraged to make their journeys throughout the civilizations of the Rainbowlands and the places in-between their own. Part of why I don’t mention a lot of the gameplay in this interview writeup is due to this; most of the mechanics are handled by random number charts. The elegance of UVG’s system lies within trusting its players to get wild with improvisation. Like a great guitar solo.

Not to get carried away with musical metaphors however, the other great strength of Rejec’s work on UVG 2E is in recognizing the strength of communication and speculation amongst players. Although the rules formerly known as SEACAT are now reframed as the SDM in the Our Golden Age setting book, the core philosophy of those rules remains the same: the dice are not your masters and the language of play should be kept as simple and accessible as possible. You only turn to your characters’ stats, skills and abilities when it makes sense, as opposed to other more traditional RPGs which often operate with increasingly complex number charts. Rejec explains his goal thus: “The ideal, for me, is a roleplaying game where the rules are not jargon, but words and sentences that any player can understand without having to study the manuals for months and months.” Mad respect. Vintage RPG also spoke with Rejec about his aspirations for a system that’s based on natural language and more when UVG 1E was still forthcoming. Rejec still considers his goal aspirational at this point, because a lot of players like him (and me) grew up with RPG jargon and post-Critical Role boom everyone is somewhat embroiled in said jargon.

Rejec’s multilingual background (he is fluent in Slovenian, English and Italian and has studied several other languages as well) plays into his world-building. There are several languages players can speak and these languages are not just, as Rejec puts it “random garbledy-gook.” In the tradition of the best conlangers, he makes up language rules for deriving consistent names from existing or extrapolated base grammars – “So, a lot of times, I’ll use some proto-Indo-European root and build up a name or word that sounds like it should mean a thing in many different I.E. languages.” In other situations, he grounds his conlangs more in existing families, such as with the Rainbowlands’ languages which coincidentally derives from his early players’ romance languages of French, Spanish and Italian.

At the heart of Rejec’s design for UVG, or really any of the games he creates under the Exalted Funeral label, is harnessing the power of roleplaying games as safe social settings. Such settings cultivate open dialogue and respect. Players should experience other worlds and cultures, no matter how different, with a spirit of adventurous curiosity. “For me, at least, that’s part of the big draw of RPGs – throwing a weird culture into the game and seeing what the players make of it.” A creator like Rejec, who knows many languages at once pictorial, textual and sensorial, is the ideal person to open players’ minds to the synaesthetic reality of UVG.

* * *

UVG 2E is now available at Exalted Funeral. Check out some of Luka’s other work too, such as Witchburner, Longwinter and Holy Mountain Shaker. You can also check out his official site and his Instagram, or join his Patreon for early looks and sneak peaks.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.