Whatever Knows Fear

This is a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #163. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

In the spring of 1971, an unlikely confluence of events occurred. In the offices of both Marvel and DC Comics, shambling swamp monsters birthed of chemicals and human bodies – and maybe just a bit of the supernatural – rose from the muck and onto the pages of Savage Tales #1 and House of Secrets #92, respectively. These were the macabre Man-Thing (the former) and Swamp Thing (the latter), who appeared on stands within a month of one-another and yet, strangest thing of all, there is no evidence of any cross-pollination between the creative teams responsible for them nor, indeed, any awareness on either party of the other’s work.

Of these two, DC’s Swamp Thing has been indisputably the more successful. Created by Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson in what was originally intended to be a standalone horror story, the Swamp Thing was buoyed not only by the work of those two creators, but also by an industry-defining run by Alan Moore that began in 1984 – two years after the character had already starred in a live-action movie (decades before such things were de rigueur) directed by Wes Craven. Swamp Thing got a sequel movie, a live-action TV series and even a toy line.

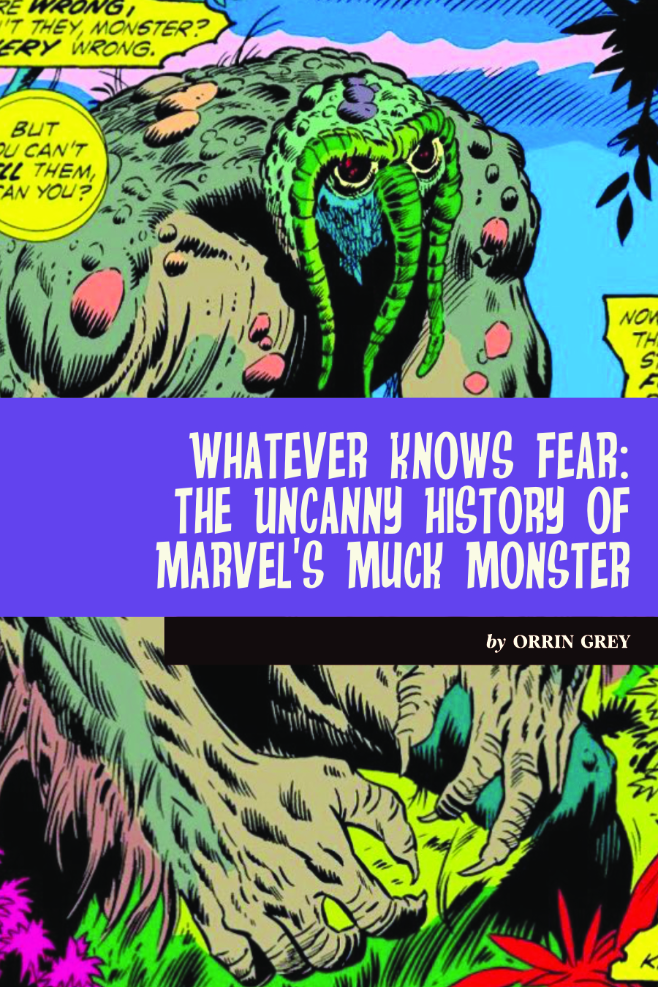

In spite of this, Man-Thing has always been my favorite of the two classic muck monsters. This has as much to do with Manny’s design as anything. It’s one of my favorite monster designs of all time, with its slumped shoulders, hunched back, and unmistakable visage. As my spouse pointed out when I was boring them with the details of this essay, the names of the two characters are actually flipped. Swamp Thing is much more human, whereas Man-Thing is much more swamp.

It isn’t just that Man-Thing’s design looks cooler to me, either – with all due respect to Wrightson’s classic depiction of Swamp Thing. The design of Man-Thing, with the roots that rim the staring red orbs of his eyes and his “carrot” nose, pay tribute to the roots (no pun intended) of the muck monster trope in ways that are absent from the Swamp Thing design.

Y’see, while Swamp Thing and Man-Thing are its most famous iterations, the idea of a human body that becomes one with the muck and mire of a swamp and rises as something else didn’t begin with either of them. It had precedents, going back as far as a legendary short story by sci-fi writer Theodore Sturgeon, which appeared in the August 1940 issue of Unknown. Called simply “It,” Sturgeon’s story set the template. But by the time Swamp Thing and Man-Thing showed up, it had already had more than a few imitators.

Most notable among these for our purposes is the Heap, which was probably the first such creature to find its way into comic book pages, appearing in Air Fighter Comics just two years after the publication of Sturgeon’s seminal short story. More than anything else, it is the Heap’s “carrot” nose that is echoed in Man-Thing’s design.

Beyond the visual, though, Man-Thing also harkens back to Sturgeon’s original story in ways that Swamp Thing doesn’t. As tragic a figure as Swamp Thing may be, his mind is still fundamentally human, even while his body is not. And while Swamp Thing may struggle to speak, he does eventually re-learn the ability, and even while he lacks it, we the readers are privy to his interior thoughts.

Man-Thing, on the other hand, has no interior thoughts, as such. As we are assured again and again in his early comics, though Man-Thing was once a scientist named Ted Sallis, just like Alec Holland (who became the Swamp Thing), the creature that rises from the muck bears precious little of Sallis within it. In one of Alan Moore’s most famous Swamp Thing stories, it is revealed that Swamp Thing is not, in fact, Alec Holland at all, but merely a conglomerate of swamp plants that absorbed Holland’s memories and intellect. Man-Thing isn’t even that, and never was. His body – which, throughout the comics, is destroyed and reconstituted several times – is made up of nothing but ooze and plant matter, largely impervious to harm and capable of squeezing through surprisingly small spaces.

More to the point, though, Man-Thing is mindless, or effectively so. A creature without much in the way of thought or memory. Instead, he is empathic. He feels the emotions of those around him, and reacts in ways that often reflect those emotions back at them. Anger and hate cause him physical pain – among the few things that do – and so he reacts to destroy the sources of these emotions, leading to innumerable confrontations and misunderstandings as to Manny’s motives. It is fear, however, that he loathes, and whatever knows fear burns at Man-Thing’s touch.

It’s a weird power for a shambling mound of muck, and we’re given something of a hand wave-y explanation that the chemicals which helped to transform Ted Sallis into the Man-Thing react with chemicals produced by the body when we experience fear to generate the burning sensation. Nobody spends much time on it, and it doesn’t really matter. What matters is that Man-Thing is not a protagonist in the usual sense. Instead, he is a cipher that reacts and reflects the world around him.

In this way, Man-Thing echoes the tragic and deadly entity in Sturgeon’s original story. Though formed around a body, Sturgeon’s “It” was also largely mindless, like a creature new-born, driven by insatiable curiosity about everything with which it came into contact. This curiosity combined with the creature’s ignorance of concepts like mortality and the fragility of other organisms was often deadly for those it encountered – and their own terror of it rarely helped.

Man-Thing was created by Roy Thomas, Gerry Conway, and Gray Morrow, but the writer who left the most indelible mark on the character was Steve Gerber, who began writing Man-Thing stories in Fear #11 back in 1972 and continued more-or-less unabated until Man-Thing #22 in 1975. In Gerber’s hands, the Man-Thing comics were emphatically what we would today call “woke,” and Man-Thing served as metaphor and catalyst for stories dealing with environmental issues, racism, toxic masculinity and a disconcertingly prescient depiction of parents’ rights groups trying to pull books from schools, to name just a few. In these stories, Man-Thing was often the unwitting hinge upon which the conflict turned, but his empathic nature also allowed us to see sides of the story that might otherwise feel too ham-handed or preachy.

Sometimes these themes were handled with relative subtlety, more often less so. The greedy land developer who wants to build an airport over Man-Thing’s swamp, for example, is named F. A. Schist. Alongside these “message” stories, the comics also featured demons, aliens, space-faring sky pirates, a suicidal clown, innumerable detours into full-on sword-and-sorcery and the first appearance of Howard the Duck, among many others. Gerber even made his exit from the title in a metafictional self-insertion that would presage similar tricks by writers like Grant Morrison.

Thanks to an unassailable early run by Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson, as well as the aforementioned Alan Moore years, Swamp Thing is generally regarded as the character with the better oeuvre. And he very well may be. But those early years of Man-Thing comics, in which Steve Gerber and a handful of talented artists made the character often earn the moniker slapped on covers of “the most startling swamp creature of all,” are absolute classics in their own right, and the macabre Man-Thing, and especially his early adventures, deserves more love than he has generally been given.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.