A Dark and Stormy Night: The Old Dark House Vibes of 13 Dead End Drive

I see board games in the store and they always look so cool and then I buy them and bring them home, I’m so excited to open them, and then I play them, like, twice… This column is dedicated to the love of games for those of us whose eyes may be bigger than our stomachs when it comes to playing, and the joy that we can all take from games, even if we don’t play them very often.

Most of the games that I cover here are what I would call – to some greater or lesser extent – weirdo games. Not to say that they are necessarily about odd subjects, though this is me, so they often are, but rather that they are board games of a type that has only really started to exist in large numbers in the last few decades. The kinds of board games that we mostly didn’t have when I was a kid. The kind you still often can’t buy in a place like Walmart or Target, but that you need to go to a specialty game store to pick up. The kind that often cost upwards of $100, so you also need to be… pretty into board games to even consider.

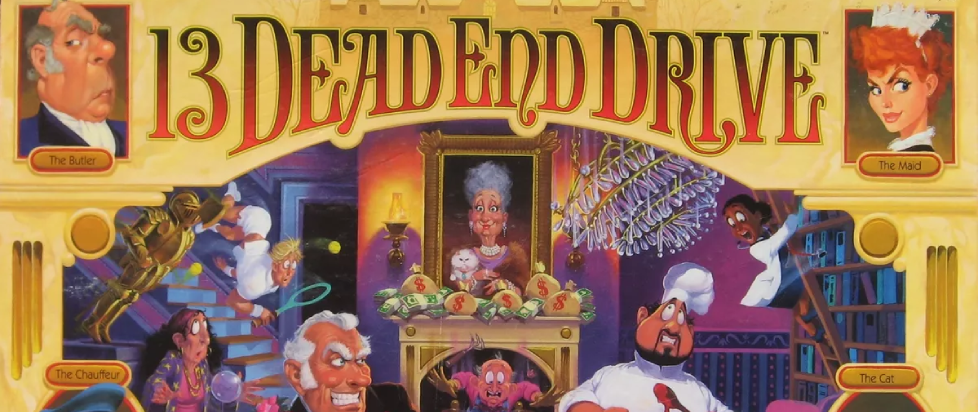

Not so with 13 Dead End Drive. Originally released by venerable board game company Milton Bradley in 1993, 13 Dead End Drive is emphatically the kind of family game that many of us grew up with – think Monopoly or Sorry or quite possibly the game’s closest relation, Mouse Trap. In spite of this, 13 Dead End Drive is, in many ways, a much weirder game than most of the ones we cover here.

Y’see, whereas family favorite board game Clue borrows the Agatha Christie-like whodunit as its template, 13 Dead End Drive goes instead for the “old dark house” motion pictures that were popular in the ‘20s and ‘30s. Had anyone who was buying family games in 1993 ever so much as seen one of those movies? Perhaps parents who grew up watching Shock Theater films on TV, but probably few others.

Regardless of whether you’ve seen any of these classic old dark house pictures or not, though, the setup is familiar. Rich Aunt Agatha has passed away without a clear heir, and a bunch of scheming friends, employees, and a cat have all gathered for the reading of her will. The problem is, only one can inherit, and it seems that Aunt Agatha left her entire estate to her favorite – whoever’s portrait is hanging on the wall. Meanwhile, everyone is trying to knock one another off with various booby traps hidden throughout the house, from a toppling statue to a falling chandelier.

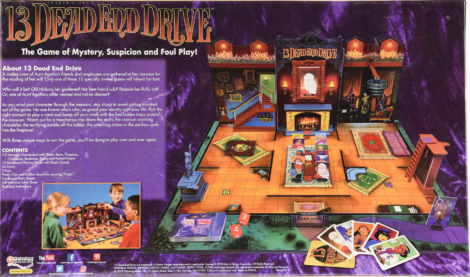

These traps are what make the game complicated to set up – it comes with 7-step setup instructions that are separate from its general rules. They’re 3D assemblages of cardboard and plastic that stick up off the game board to make a sort of mansion set, and the traps can be activated to literally “knock off” the pawns placed on the trap squares. This is pretty much the game’s whole gimmick but, ironically, you don’t need any of it to play.

You activate a trap square by playing a matching trap card when a pawn is on it. Meaning that the mechanical traps are cute but ultimately superfluous. You can simply get rid of the pawn by playing the trap card when they are on the relevant square, and don’t even have to set up the whole 3D mansion at all – though, of course, where’s the fun in that?

Without all the 3D set dressing, the game is essentially a matter of luck, timing, and bluffing. On your turn, you can move any two pawns, not just the ones of the characters you control. What’s more, the characters in your hand remain secret until they are “knocked off” or until the end of the game. The goal is to get one of your pawns out the front door while their portrait is hanging on the wall, but the portrait changes throughout the game, most often when a player rolls doubles on the two dice, or when the portrait that would otherwise come up belongs to a character who has already been taken out by one of the traps.

This bluffing mechanic, as much as the traps and the accoutrements of the mansion – complete with a storm raging outside the window – is what makes 13 Dead End Drive capture the tone of its old dark house forebears surprisingly well for such a mainstream confection. Even more so than in a game like Clue, nobody knows who is really responsible for what until it has already happened, and a bold player will often put their own characters in harm’s way in an effort to fake out their opponents.

In addition to the 1993 original, Milton Bradley also published a 2002 spin-off called 1313 Dead End Drive. It was (perhaps sadly) not Munsters themed, but rather changed the basic mechanics of the game somewhat and expanded the number of heirs from twelve to sixteen. It also shrank the size of the board – the original game, to accommodate its many traps, comes in a particularly long box – and made the artwork even more kid-friendly.

Both the Milton Bradley versions have been out of print for a while, but for the last few years, Winning Moves Games has been republishing an edition of 13 Dead End Drive, with art and design that almost exactly mirrors the Milton Bradley original. I’ve never played the Winning Moves Games version, which was named one of the best kid-friendly games of 2022 by Good Housekeeping – my own copy is a Milton Bradley release that I got from a yard sale discard pile – but as near as I can make out they are basically identical.

It’s not a game I play often. Setting it up is a bit of a pain and my copy is not in the world’s best shape. But as a devotee of the kind of old dark house pictures that it’s aping, the simple fact that it exists at all scratches a certain itch, and I’m glad to see someone bringing it back into regular rotation.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.