What Are Ya Buyin’?

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #162. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Reframing the boundaries of what is seen and unseen…

———

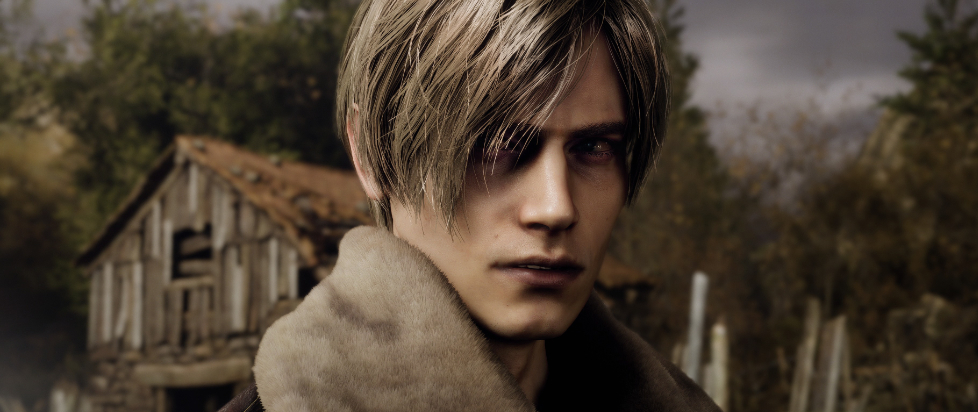

Few games feel as perfect of an experience to me as Resident Evil 4. Since its release on the GameCube in 2005, I’ve continually returned to this game in a fashion I haven’t found in really any other game that exists. The encounter design coupled with the lumbering control scheme makes the experience of playing the game tense, even heart-wrenching at times.

The narrative, following franchise favorite Leon S. Kennedy as he tries to rescue Ashely Graham, the President’s daughter, from a mysterious cult in Spain, knows its audience. It’s campy, over-the-top and doesn’t spend too much time overexplaining itself. The over-the-shoulder gunplay also set the games industry down a course of philosophies that are paramount to game design today. So, I was curious how Resident Evil 4 Remake would grapple with the legacy the game has garnered while also justifying why this remake was needed.

From what I’ve played of the remake thus far, I’ve come to feel that while I am immensely enjoying the game, I wonder why it exists. On a cosmetic level, Remake is definitely one of the better-looking games on this current generation of consoles. Whereas the original game could sometimes feel like Leon was traversing a series of tightly constructed sets, Remake has a more lived-in, interactive feel to it. Leon reacts to weather changes, ambient lighting casts shadows over the environment that often enhances feelings of dread and tension, a flashlight has been added to the experience that creates creepy moments in dark environments.

All of these additions certainly look great, but there’s also a feeling of more for more’s sake. Gone is the linear progression of the original game that constantly propelled Leon forward, replaced instead by a semi-open design where the main path is supplemented by optional side quests. These quests are fun, but derivative. “Kill 3 rats” type shit pads out the game, offering minor rewards to buy further armaments for your attaché case.

A major change to Resident Evil 4 this go-round is the ability to move and shoot at the same time – an experiment lifted from Resident Evil 2 Remake that worked well. Where the added mobility in RE2 Remake worked in capturing the frenetic feeling of walking into a nightmarish situation and cobbling together a solution, there’s something about this addition in 4 Remake that doesn’t sit the same to me.

The iconic town square sequence that kicks off the full introduction to Resident Evil 4 is a good indicator of this. In the original, the town square sequence teaches the player that in order to survive, you’ll need to be fairly precise in your shots, and you’ll need to balance your offensive prowess with a keen sense of when to move and recalibrate the situation. The game also introduces the Shotgun and a grenade, all of these additions make the sequence an emergent teaching moment for the player that couples intense enemy encounter design, situational awareness and inventory management.

In Remake, they faithfully recreate this sequence hitting all of the same beats while adding in a few new ideas to keep things fresh. The most notable change to me is that with the addition of added mobility comes an increase in the amount of enemies coming after Leon. While this does add to the sense of danger Leon is in, it also makes the encounter feel a bit muddy in ways that do the elegance of this encounter a disservice.

I found the additional movement options, the added quick swapping of weapons and even the parry (which I find fun as hell to use!) all sand away some of the friction points of the original design in ways that make the new iteration feel a bit derivative – an ironic quality given that this game is largely the forerunner to this kind of action-horror genre that permeates the industry today.

While these changes feel fairly good in the moment when I’m playing the game, I find that upon further reflection after a play session the experience ends up being hazy, an amalgamation of modern game design instead of being in conversation with the legacy it holds upon its shoulders. In an age where everything I love seems to be on a timer ticking toward an inevitable remake, I yearn for these projects to upend the version of themselves that came before.

We talk a lot about preservation in the games industry today. How so many titles are wiped from the record, never to be seen again. Resident Evil 4 isn’t one of those titles. It’s been re-released on practically every gaming device that can support it. I wonder then, what are we buying when we get this remake?

While many people had opinions on the successes and failures of the first installment of the Final Fantasy 7 Remake, what I enjoy about that title is how it creates an experience that largely replicates the original while also placing it outside of time from its progenitor. It’s interested in what it means to “remake” something and how the passing of time rejiggers our own perception on what is true and what was. Resident Evil 4 Remake is a great recreation of the original game, one that I’m finding pleasing to revisit on a new console, but I do wish that the development team took more risks in interrogating what a remake could mean for a title like this outside of more fidelity, more quests, more mobility and less friction.

———

Phillip Russell is a Black writer and podcast producer. His writing explores the intersections between pop culture, Blackness, and our connection to land and identity. Follow his work on Twitter @3dsisqo.