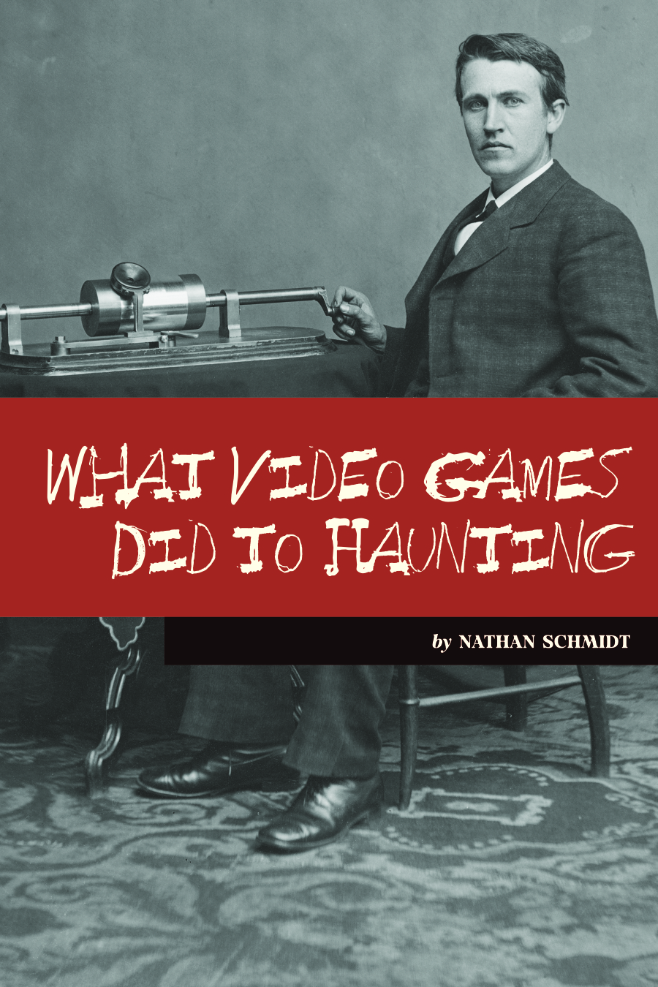

What Video Games Did to Haunting

This is an excerpt from a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #162. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

I have a question for you: Where are all the haunted videogames?

“Why, right there on Netflix,” you’ll tell me. “Choose or Die just came out last year.”

Aha, see, you’ve misunderstood my question. Choose or Die is a made-up story about a haunted videogame; it’s just a movie. I want to hear about cartridges, CD-ROMs and hard drives that are haunted by real, actual ghosts. What’s more, I think I even have good reasons for wondering why there aren’t more of them.

Please, allow me to explain. Allow me to tell you about Thomas Edison’s ghost phone.

In the nineteenth century, it was pretty common for emerging media to be attended by reports of haunting. One of Edison’s stated goals for the phonograph was that it would allow users to record the dying words of their loved ones, which is a pretty ghastly idea; a photographer named William Mumler used fancy, innovative exposure tricks to take “spirit photographs” that purportedly included the ghosts of dead loved ones. (An instantly recognizable one features Mary Todd Lincoln with the ghost of Honest Abe.) Samuel Morse’s first message sent via telegraph, “What hath God wrought,” resonates with an immediate sense of foreboding. As media scholar Jeffrey Sconce describes in Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, it was not an accident that the advent of the telegraph near the middle of the nineteenth century also saw the heyday of the Spiritualist movement, where everybody in America was trying to talk to the dead while mediums spewed fake ectoplasm all over the place (it was a wild time). Spiritualist mediums frequently set themselves up for comparisons with telegraphs.

Sconce records the story of one infamously haunted nineteenth century house, the Fox cottage in Hydesville, New York, being described as “charged with the aura requisite to make it a battery for the working of the telegraph.” The telegraph, in this case, refers to the ability of the Fox sisters to hear the “spirit rappings” of ghostly interlocutors in the walls. The connection between the telegraph and the World Beyond actually has a coherent, if faulty, internal logic, as Sconce describes: “For the Spiritualists, the bodiless communication of telegraphy heralded the existence of a land without material substance, an always unseen origin point of transmission for disembodied souls in an electromagnetic utopia.” Before the telegraph, people only experienced disembodied communication through the mail or through inexplicable psychic phenomena, which you could call hallucinations or paranormal visitations depending on your point of view. When the telegraph and the phonograph came along, they were bound to remind people of other stories about disembodied voices.

As the nineteenth century progressed, Spiritualism came to be absorbed by more empirically-minded scientific bodies like the Society for Psychical Research, but the connection between electricity and the hereafter was only cemented further. Thomas Edison had plans, late in life, to devise a “spirit phone” which would allow users to speak to the dead “by scientific methods” – none of that mediumship hocus-pocus – although he never managed to build a device that operated to his satisfaction. Nikola Tesla, who did not believe in ghosts, nevertheless also stoked the fire of the electric paranormal with his wizardly wireless displays that would light a fluorescent tube in the middle of an empty stage.

In other words, it’s not that nineteenth-century people were unusually gullible when it came to new technology. It’s just hard today to imagine a world where the possibility that you could record any sound or freeze any image felt new and exciting. Many people in the early days of photography showed up for their first and only portrait session as a corpse, because families wanted some memento that would be more permanent than memory. New technologies for audio and video capture created a disembodied version of you, capturing some part of you that would outlast your decaying corporeal form. It only sounds unusual to associate these technologies with ghostly apparitions because we have gotten so accustomed to constantly disembodying ourselves.

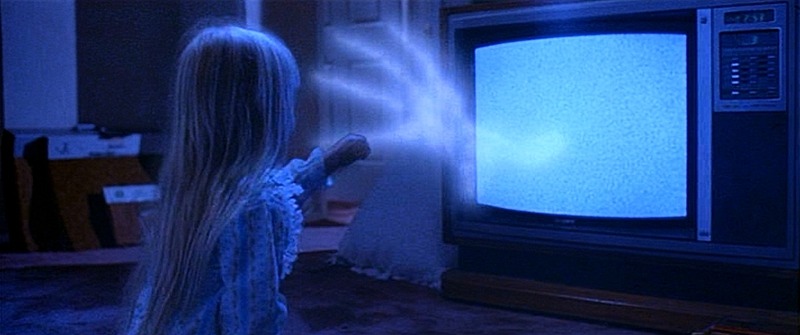

Here’s where my concern about haunted games comes into play: these technological innovations felt haunted to their early adopters because they were new. Electricity, not yet understood as a particular arrangement of electrons, seemed to occupy a netherspace between intangible force and tangible reality. The telegraph, in its unprecedented sundering of time from space, called the corporeality of the whole world into question. Sconce even describes cases of haunted television sets that extend well into the twentieth century, like the one immortalized in Tobe Hooper’s 1982 Poltergeist. By this logic, there should be a plethora of stories about haunted VR sets, haunted mobile games – maybe even a haunted Steam Deck or two. Instead – and this is the thing that befuddles me – when they are talked about at all, haunted videogames are almost always retro and retroactive. Electric media was haunted from the beginning, so now that our most popular forms of communication and entertainment are electrical, why aren’t there more hauntings?

As Grace Benfell at Paste wrote about the first Haunted PS1 Demo Disc: “A PlayStation 5 cannot be haunted. An original PlayStation can be.” I have spent a lot of time on the internet looking for haunted videogames, and I have to concede that, as far as I can see, Benfell is correct: no haunted PS5s (not even the ghosts can get one). But the history of haunted media suggests that the more recent a technological innovation is, the more likely it is to be haunted. So, what happened? Why are Majora’s Mask, Pokemon Red and Blue and Morrowind our most famously haunted games? Why can’t I get a haunted copy of Elden Ring, or Gran Turismo 7? Something about the very meaning and nature of haunting must have shifted, and I believe that videogames are the culprit.

———

Nate Schmidt is a contributing editor for GamerswithGlasses.com, and holds a PhD in English from Indiana University Bloomington, where he studies the relationship between science writing and science fiction. His work can also be found in The Rambling, and in the Bloodborne anthology Blood Echoes, out later this year from Tune and Fairweather Press. Follow him on Twitter at @corndruid (for real, tell me if you have a true haunted game story).

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 162.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!