1982

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #161. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

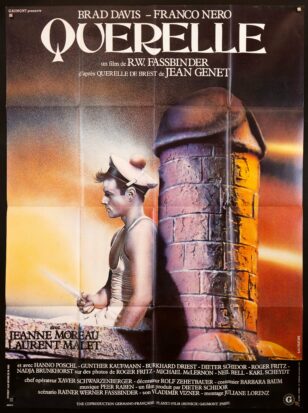

Hello good wanderers! This month we’re in 1982 and taking on two grand pieces of homoeroticism, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s final film Querelle and Judas Priest’s Screaming for Vengeance.

* * *

For Wes, the train was always a space where a new face could create a new reality, like the face of this man (that towered over him) leaning against the glass (a veritable Clark Kent. Pecs bulging. A loc taking the place of the classic curl. Ready to whisk him away).

He didn’t let his location limit him. Work was also a space for the mind to run wild. In the moments before he put down his briefcase and steeled himself for the case in which (he the paragon of justice would ensure the dastardly fiend) a 20-year-old caught in the midst of a fight gone wrong was rotting in prison (so he couldn’t flood the streets with blood and poison ever again).

Then after (a good day’s) work bolstering the (just leviathan of society’s criminal justice) system, the lawyer (and dream weaver) returned to the train (his palace of thick-aired sweat laden fantasy) and once again thought about another passenger (this one an Adonis, warm breath carrying him into forever).

As the dreamer left the station and got to his flat, the usual call for money came from the usual yellowed teeth and the usual sad gappy smile deep set into the usual mahogany face. Wes gave the usual halfhearted shrug and kept walking.

* * *

Adapting Jean Genet’s 1947 novel, Querelle feels like Vaseline was smothered on the lens between each shot of Xaver Schwarzenberger’s cinematography. Even the streets have a slight glaze to them in the sickly over lit yellows. The port city of Brest is presented as less tangible space and more manifestation of the sweaty fantasies of the western queer male imagination – with every actor barely clothed and glistening. There is also an overwhelming amount of not-at-all concealed phallic imagery, from the guns, to the architecture to the poster of the film itself.

However Rainer Werner Fassbinder doesn’t sanitize or idealize the fantasy space he’s operating in here, instead he dives straight into the thorniest bits. The two characters that this gets most keenly explored with are Mario (Burkhard Driest) and Nono (Günther Kaufmann).

Husband to the lady who owns the haunting hedonist bar where much of the film takes place (Feria), Nono runs the less than legal side of his wife’s business and also is the only speaking Black person in the film. As such, the portrayal ends up being one of the harder ones to untangle. There is a read of this film where Fassbinder is uncritically constructing Black men as hulking beast of power and violence. His costuming is certainly meant to emphasize his size, moving between a bulky suit and a tank top that barely clings to his frame. However, I think it’s more compelling to read this as yet another engagement with the sexual fantasies of white gay Europeans. Whiteness and its gender norms are constructed in relation to The (racial) Other, whether that’s in terms of dominating them (see: the masculinist construction of the myth of the American cowboy) or being under threat by them (see: how civilizational feminism in France relies on defining Muslim men as the primary source of sexual violence). White queer European men are by no means excluded from that. Prominent examples of this can be seen with men like Lawrence of Arabia who were part of imperial forces and were able to use that position to explore their sexual desires using people of color while also being part of the regimes which enforced many of the homophobic laws which still oppress the queer people in those countries to this day.

Mario is a corrupt cop in the pocket of Nono and Feria, who is deeply infatuated with the protagonist Querelle. His costume is less Precise Recreation and more like something someone would wear to a Halloween club night. He is the Man In Uniform In Extremis and creates a space to problematize that fantasy. The complexities here arise because on the one hand there’s something in proscribing eroticism into the thing that has/does oppress you. After all, at the time in which the film was set and even the time when it was filmed, there were still a wealth of explicitly anti-queer laws on the book in the West. On the other hand, big threads of white queer manhood in the West have been deeply tied up with fascism – with one of the most prominent examples being the masculinist gay Nazi Ernst Röhm. But again, this is not a film of didactic moral judgements, and he exists as a complicated figure in that collage.

Querelle portrays a feeling of fantasy that doesn’t exist in isolation, and is instead colored by the world which surrounds, particularly engaging with the complex political space of the white European gay fantasy.

* * *

I don’t think you ever forget your first time rushing through the air clinging to leather with just their body/your breath for company.

The world looks so different at a hundred miles an hour, your corporeal form now a black blur on the horizon as you paint your stroke on reality in your tightly sculpted armor.

In this state anything is possible as blood becomes air becomes leather becomes oil becomes warmth becomes speed becomes lighting becomes revolution.

Then it all stops. The journey over. But it wouldn’t be the last.

* * *

Christopher slumped into his gilded office chair. It had been cruel to drop the boy like that. He gently removed still-shining brogues. Cruel but necessary. He removed his tie and undid the top two buttons on his now-wine-stained shirt. There was too much of a shine in his eyes, too much weight to his step – the boy was forgetting what this was.

Christopher got up, strode past his desk, stepped over the remains of a wine glass and over to the bloodied mark in the wall left by the boy’s fist.

What had really been lost? He’d come back. He always did.

Christopher called the handyman to have it fixed later that evening.

* * *

For the men of Querelle, pain and pleasure are inseparable. In any given scene it’s impossible to tell whether these men are about to kiss or fight – and the answer is often both. As Lt. Seblon (Franco Nero) looks over his subordinates from his office and monologues into a tape recorder, he notes how he can’t look at the broad shoulders of these men without thinking about the capacity of these men for killing.

That underlying violence is present in every movement these men make and in every frame. A gun at the table. A knife at the throat. The acting is all very intentionally stilted, with overloud blunt deliveries and sharp movements. With his off-kilter direction, Fassbinder paints a portrait of a Western masculinity which is deeply entrenched in violence and at war with its own desires. There are constant power games, with the insistence that one position or another means someone can engage in homosexual behavior without sacrificing their manhood. Like how Nono insists that because he doesn’t kiss/love the men, his encounters maintain his manhood. Or Mario masks his barely-concealed desires in prodding and teasing, the same for Theo in regards to Gil.

The connection between violence and desire is once again neither lionized nor chastised by Fassbinder – again choosing to push and explore more than dictate.

* * *

The phone slams against the receiver.

He smiles.

His mouth stops.

He smiles again.

His face pauses.

He traces fingers against the steamed-up glass.

His leather glistens wet in the moonlight

He wipes mascara by handThe smile creeps across his face once again.

* * *

When the fantasy and violence collide, they create a fever. The great fever pitch of desire burns bright and then burns itself out. Throughout the film there is this overwhelming feeling that this homoerotic fantasia is only temporary, haunted by the oracle and owner of Feria Lysiane (Jeanne Moreau) singing that “each man kills the thing he loves”. Querelle betrays both his beloved Gil and his brother, falling into the arms of Lt. Sebon who it seems he will inevitably betray as well.

Yet there’s still a glistening beauty to it all. Sure the ride ends but maybe the rush was worth it? The euphoric rise worth the painful fall? Maybe to love something is to embrace the inevitability of its end.

* * *

-60 bpm-

Cigar smoke on my breath

-70 bpm-

Our eyes met between the beats

-80 bpm-

Rushed together, closed the distance

-90 bpm-

Fevers blooming in our naked chests

-100 bpm-

Fluids flurry, our destiny is nigh.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer. You can find her Twitter ramblings @naijaprince21, his poetry @tayowrites on Instagram and their performances across London.