Horror’s Path Through Christian Cosmology

Inside the large umbrella that encompasses everything we call horror, nothing gives me catharsis like religious horror. Religious horror refers to stories within the larger horror umbrella that treat the details of specific, existing religions as fact within their fictional universes. For most films in the West, this means a world swept up in Christian cosmology. Think of terrible demons in such films as The Exorcist (1973), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), and Hereditary (2018). Yet religious horror often means more than just playing Christianity’s rules straight. Often, filmmakers use religious horror tropes to comment on the role religions like Christianity plays on our lives. They ask questions like, “What directions should we be heading?” and “How will our religious beliefs impact our future?”

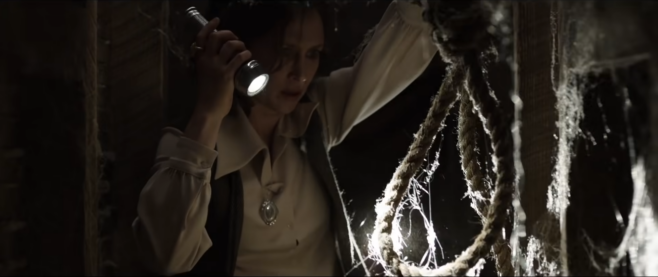

Two popular media experiences express this fact plainly: The Conjuring (2013) and Midnight Mass (2020). Even on their faces, the two could not be more different. The Conjuring, directed by James Wan and distributed by Warner Bros, is a true spookshow, a traditional ghost story with a villainous, Satan-worshiping witch at its center. Its heroes, Ed and Lorraine Warren (played by Patrick Wilson and Vera Farmiga) descend from a long history of heroic Christian exorcists in the genre.

Midnight Mass, on the other hand, is a Netflix miniseries created by Mike Flanagan. Its narrative concerns an entire fictional town rather than a beleaguered family, and its relationship to religion, specifically Catholicism, becomes the central thematic conflict of the series. The threat in the show rests on a charismatic, young priest who is secretly a vampire. Much like The Conjuring, then, Midnight Mass focuses on a traditional supernatural source. Unlike the former, however, Midnight Mass chooses to use the vampire to comment on the pitfalls of religious mania and ecstasy.

Nothing better contrasts the approach of these two pieces of media than the reveal of their supernatural threats. In The Conjuring, when Ed and Lorraine Warren first enter the Perrons’ house and hear of their troubles, the problem is immediately attributed to the demonic. Ed Warren’s diagnosis comes quickly after complaints of rotten meat and pervasive chills. “Well,” he deliberates after sharing a concerned look with Lorraine, “rancid smells could indicate some sort of demonic activity.”

And indeed, the film goes on to prove him right. Supernatural attacks are preceded with trembling and falling crucifixes. Clocks stop at 3:07 AM, the two numbers considered most sacred in Christian numerology. The eventual reveal of the ghost’s identity, a Satanist witch named Bathsheba Sherman, creates an interesting thematic foundation. In this universe, somehow, a woman who would be subjected to a witch hunt is its ultimate villain, an evil mother who sacrifices her child to the devil at exactly 3:07 AM. Ultimately, The Conjuring carries a very reactionary, conservative push in its overall story. Opposition to the church must by necessity be evil. Its heroes, Ed and Lorraine Warren and the victimized Perron family, also uphold an image many conservative Christians cherish: the traditional nuclear family. Indeed, the crux of the film’s climax rests on saving Nancy Perron from demonic possession. In essence, The Conjuring is about keeping a struggling family together with the power of Jesus.

And if The Conjuring is all about that staying power of traditional Christian values, Midnight Mass chooses a story all about the pitfalls of fundamentalism. As stated before, the Netflix miniseries focuses on vampirism told through the lens of the Catholic faith. Our mysterious priest, Father Paul Hill, creates miracles by feeding the town of Crockett Island vampire blood. Disabilities and illnesses are healed. Aging reverses. So deeply does this religious narrative take hold that the characters never even mention the word “vampire.” Instead, the creature which originally infects Father Paul Hill is referred to only as “The Angel,” even in the credits.

As the town falls for Father Paul’s creed, however, the narration focuses on the faith journey of Riley Flynn, a disgraced prodigal son. We’re introduced to Riley Flynn after he kills a young woman in a drunk driving accident. At first a devout Catholic like much of his hometown, Riley’s return to Crockett Island makes it clear that he no longer believes. In a more traditional horror film, the vampiric menace of the town would perhaps convince Riley to take up the cross once more. Think Mel Gibson’s character in Signs (2002). Instead, however, Midnight Mass gives us a beautiful arc about integrity, faith, and dignity.

The culmination of this arc begins in the episode titled “Book V: Gospel.” Riley Flynn’s arc in the episode shares some similarities with previous installments but differs wildly in the stakes. After being attacked by the vampire that turned Father Paul Hill, revealed to be the parish’s old priest Monsignor John Pruitt, Riley discovers he himself has become a vampire and is trapped inside the location of his previous AA meetings. There, Father Paul endeavors to convince Riley that his change is no monstrous act but a miracle. The dialogue in this scene is extremely telling, combining Catholic doctrine, the prayer of serenity, and Biblical scripture to produce a frightening religious sales pitch.

One of the most chilling segments of this moment lies in Father Paul’s use of the Bible to justify his lack of remorse in murdering and draining a former resident of Crockett Island, Joe. “Cleanse our consciences so that we may serve the living god!” the priest exclaims. “I read this passage and the graces of the Holy Spirit rained down on me. He had taken that guilt, cleansed my conscience, for I had simply been His vessel. Done his will.” A beat. “A murderer, maybe. So was Moses. Joseph. Paul, my namesake.” More than any scene of carnage, this moment terrifies the audience. After all, not a single one of us has ever experienced a vampire attack. But how likely is it that you find a monster justifying something truly dangerous and soul-crushing with a bit of Scripture? How easy is it, especially now, to discover a religious bigot justifying the shedding of blood for the sake of their own personal crusade?

Ultimately, religious horror provides a unique opportunity for creatives outside of the cliches we associate with the sub-genre. Midnight Mass proves that the genre’s foundations are fertile enough to innovate storytelling even as more mundane works like The Conjuring give us more of the same banal supernatural fare. While the latter ultimately repeats the croon of an old time religion long overdue for the grave, the former promises a better future for smart and compassionate stories in the bloodiest genre.

———

Lyana Rodriguez (they/them) is a queer writer living in Miami, Florida. You can find more of their work on their blog, Dark Intersections.