Bombs Bursting in Air: The Other Black Sunday (1977)

“You can’t cancel the Super Bowl; that’d be like canceling Christmas.”

Today, we’ll be talking about Black Sunday, but not the Mario Bava one. Which makes me wonder if there was a time when folks who aren’t horror nerds had to be told that Mario Bava’s was “not the one about flying a blimp into the Super Bowl.”

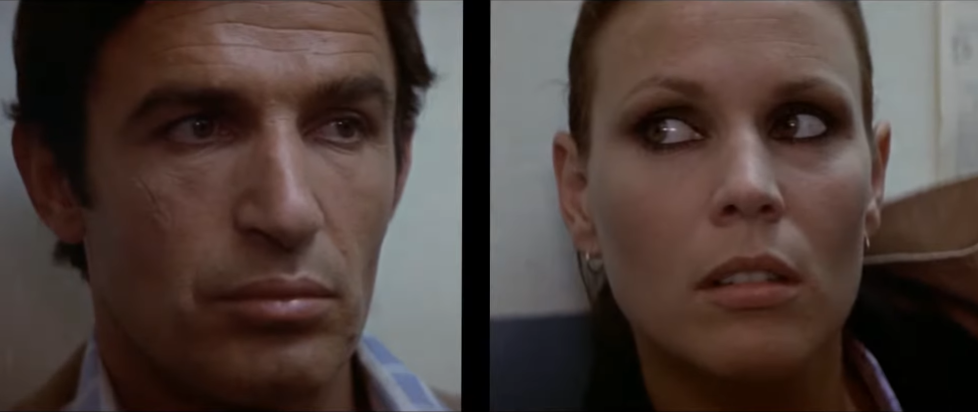

Not that John Frankenheimer’s 1977 terrorism thriller doesn’t have plenty of horror bona fides. It’s adapted from a novel of the same name by Silence of the Lambs author Thomas Harris, and helmed by the director of the 1979 mutant bear movie Prophecy (I’m sure Frankenheimer would have appreciated me remembering him as such). Its stars include Robert Shaw of Jaws fame, Creepshow’s Fritz Weaver, and even a brief appearance by Tom McFadden of A Nightmare on Elm Street 2. Not to mention Bruce Dern, of course, and Marthe Keller, playing the two would-be terrorists.

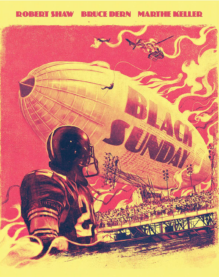

For those who aren’t at least familiar with the film’s logline and black-and-white poster, complete with bold claim that, “It could be tomorrow,” the premise of Black Sunday involves a plot by the Palestinian militant organization Black September to plant a bomb inside the Goodyear Blimp and detonate it over the Super Bowl. This naturally situates the film’s politics within a fairly narrow window – pro-U.S., obviously, but also at least ostensibly Zionist and anti-Palestinian.

I am not someone with a lot of background in the subject. I know, of course, the story of the so-called “Munich massacre” at the 1972 Summer Olympics, which was tied to Black September and obviously provided at least a partial inspiration for the plot. But I can’t really speak at any length about the film’s politics, or its position on or amid Israeli-Palestinian relations, save to say that it simultaneously highlights the “special relationship” between the United States and Israel while also doing a surprising job of humanizing the members of Black September that we see.

Perhaps most laudable is the ways in which it shows that, while Robert Shaw’s Mossad agent may be emphatically the “good guy” here, he has frequently used the selfsame methods as his enemies, and the United States isn’t exactly innocent, either. These may be small moments, lines of dialogue and brief scenes, but it’s nice that they’re there at all.

This could all be due to the fact that, according to Frankenheimer, he didn’t want to make a picture that took political sides. “It’s no more a film about the Mideast crisis than it’s a film about football,” he told the New York Times, while the movie’s producer, Robert Evans, quotes Henry Kissinger in telling him, “You can’t make it a political picture. You can’t take sides. You can’t make it anti or pro anyone.” How much they succeeded or failed at that is up for debate.

But again, I’m not here to discuss the politics of Black Sunday. For that, I recommend you seek out some voices that are more knowledgeable about the conflict between Palestine and Israel – preferably those directly affected by it. What I’m here to do is talk about the movie itself and its new Blu-ray release from Arrow.

Watching the film on Blu-ray was my first time actually seeing it, though I was, of course, familiar with the premise and that key art of the blimp crashing into the Super Bowl. (You’ll note that, in all the artwork, the blimp simply says “Super Bowl” on the side. We’ll get to why that is in a moment.)

By far the most fascinating thing about the film – which is, for the most part, a solid political thriller helped along by Frankenheimer’s almost documentarian style, strong performances, and a tense John Williams score – is the Super Bowl setting. Specifically, the picture’s climactic moments were shot during Super Bowl X in 1976, with Robert Shaw and some of the other principal actors on the field as the Steelers went up against the Dallas Cowboys in the background.

These days, such a spectacle wouldn’t be as impressive. They would simply stage a Super Bowl, complete with a cast of thousands of extras, or, more likely, fill one in with CGI. Then, we could see the blimp crashing into the stands in real time in ways that Frankenheimer instead has to suggest with clever edits. Of course, it would be a cartoon blimp, crashing into cartoon stands, filled with cartoon spectators. There’s something much more stunning about them literally letting Frankenheimer and company film on the sidelines of an actual Super Bowl, while the real teams played for the championship just beyond them.

Equally impressive in 1977 – though it would, again, be less impressive today, where media monstrosities like Disney can secure an agreement with just about any brand in the world – is the use of the real-life Goodyear Blimps in the film. This is especially startling, since the blimp is the weapon by which the terrorists intend to claim thousands of lives.

This unlikely arrangement reportedly came about because of Frankenheimer’s relationship with Goodyear, with whom he had worked on his 1966 film Grand Prix. In fact, Frankenheimer was given access to all three of the blimps employed by Goodyear, but there were a few conditions. Namely, “The picture must make it clear that the pilot did not work for Goodyear. The final explosion of the blimp must not come out of the word ‘Goodyear.’ And the blimp must not be used for gratuitous violence, such as people being churned up by its propellers.”

There was one other condition, not mentioned there, which was that the word “Goodyear” could not appear on the blimp in the film’s promotional art – hence the words “Super Bowl” sprayed across the sides on the poster, or the film’s title on the Blu-ray cover.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.