Reviews Vs. Advertising: A Response to IGN’s Dan Stapleton

A game review shouldn’t resemble advertising. Through depth of argument or emotion, the review should reflect the personal reaction of the critic. When we know the person behind the review, we know a truth not driven by dollars – a precious thing given the countless individuals wanting our money.

And a review score, if provided, summarizes the ultimate feeling of the reviewer.

———

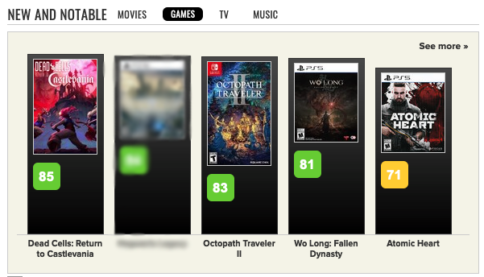

In a column titled “‘Another 7, IGN?’ Why So Many Games Score 7 and Above,” IGN Reviews Director Dan Stapleton explains why “so few reviews on IGN end up on the bottom half” of the 10-point review scale. His first point resonates: There are too many games to review. IGN must choose what to cover based on what people want to read about.

After a reasonable three paragraphs about a problem faced by every game publication, Stapleton gives the game industry a fat kiss. He says if a game “does look great” in advertisements, “it usually ends up being at least okay.” This happy camper seems unaware of the many people who experience disappointment after they play a hyped release.

Stapleton further reasons when “so much time and money is spent creating something,” the game will rarely score below a 6. But if 6 is IGN’s cutoff point, why is his article based on the premise that IGN tends to give everything at least a 7?

In his final paragraph, Stapleton reveals that IGN publishes predictable reviews for the benefit of everyone’s eternal happiness:

“When it comes to the big events they’re usually safe bets, and in most cases the question isn’t if they’ll be good but how good they’ll be. But when we have to choose, we’d much rather tell you about something we think you should experience than hammer something you shouldn’t. That’s just more fun for everybody.”

Back in his introduction, Stapleton implied IGN wants to help readers understand if “something is actually as good as it appears to be in ads and previews.” Yet above he suggests that almost everything is as good as the ads and previews – and that IGN prefers not to make anyone feel bad about games that miss the mark.

Stapleton’s contradictory stance begs for a cynical response: IGN largely reinforces the effects of advertising but is too cowardly to admit it.

———

“Who gives a shit?” you might say. No one would accuse of IGN of being a bastion of journalism. And if IGN wants to be a modern extension of the enthusiast press of yesteryear (GamePro, Nintendo Power, and so on), what place does real criticism have at the publication?

I have three counterpoints.

First, Stapleton bothered writing a column to prop up IGN’s legitimacy. IGN cares about how people perceive it, and we shouldn’t allow it to pass off a nonsensical argument as an acceptable standard.

Second, as reviews editor of one of the biggest game publications, Stapleton has considerable power. I imagine, at the very least, IGN’s reviewers feel pressure to conform to Stapleton’s viewpoint on game quality and advertising. It’s shameful when a critic can’t say what they feel.

Third, and most significantly, Stapleton’s logic is widespread when one considers the routinely high Metacritic averages for games. This fact has tremendous ripple effects that can affect other publications wishing to support honest criticism.

The game industry expects most of its hyped products to receive a positive review and a score of 7 or even higher. Failure to play into this expectation can result in the loss of review codes and heat from publicists, for example. The game industry enjoys a vicious grip on the press thanks to the spineless approach of publications like IGN.

IGN and the industry’s insistence on high review scores also influences a legion of minions who function as unpaid marketers and online muscle. When some readers see a reviewer step out of line, they will attack the writer and the associated publication like savage weasels, rather than confront the substance of a differing opinion. I doubt this immature lot would have as much fire in their bellies if IGN (and others) regularly promoted actual dissent.

———

I once believed review scores were an abomination. Get rid of the numbers, I’d say. Focus on the soul of criticism, words.

This perspective, both understandable and grumpy, is outdated. Yet a few publications, for various reasons, don’t have review scores. When you scan a list of reviews on Metacritic, you will find scoreless reviews at the bottom.

While part of me admires the spirit behind these outliers, we live in a world where numbers carry weight. Why not use them as part of a commitment to genuine, divergent opinions? In “On Videogame Reviews,” Tevis Thompson gets it right: “Numbers are subjective too, and no official review policy can change that.”

There’s an old idea in statistics: Torture the data, and they will confess. When most people glance at a review score – whether a 10, a 6, or a 2 – they desire a confession. But the priests, the big editors, must encourage us to talk to God in the first place.

———

Jed Pressgrove is a game, movie, and technology critic. His work has appeared in Unwinnable Monthly, Slant, Paste, and Monkey Island Chronicles, the 30th anniversary Monkey Island book published by Limited Run Games. He’s been writing at his award-winning blog Game Bias since 2014.