When Dwarves Won’t Do What You Want Them To

The Steam version of Dwarf Fortress looks misleadingly like other builder games. The first tasks are universal: establish shelter, and a reliable source of food and water. Tap your resources, and build out work pipelines. I know how to play these games – often to the detriment of becoming someone who bemoans my settlers for starving because they just aren’t gathering food fast enough – and these habits initially make me very bad at playing Dwarf Fortress.

The early mistakes I make in Dwarf Fortress are the kind that assume that if I have a woodcutter, they should, at all times, be cutting wood, to supply some kind of wood industry. To burn for fuel, to build furniture – where craftsmen and furnace operators also work constantly, and cyclically. This is not how dwarves work, and I end up with a surplus of wood, cursing my colony to constant hauling of logs over any other task. In another starter colony, I rely too much on the assumption that you can hold out with your starting supplies for a little while, and my dwarves eat all the plants I needed to brew into alcohol. Everyone dies of dehydration when the rivers freeze in winter.

These early mistakes only suggest that Dwarf Fortress is actually just more complex than other builder games – and that I just need better workflow. There’s a reason stupid dwarf tricks exist: its simulation is deep, and that allows for extensive engineering. But the reason Dwarf Fortress doesn’t play like other builder games isn’t because of its environment: it’s because of the dwarves.

So when I become better at playing Dwarf Fortress like any other builder game, a different problem emerges. I refine my beautiful little pipelines, and suddenly my dwarves aren’t interested: they’re living their own lives, of leisure, prayer, and rest. Enemy corpses will not be disposed of, no matter how traumatizing they are for people to walk past, and my blueprint for a new hospital is going ignored. There is drinking to be done, and they’ll get back to work when they’re ready.

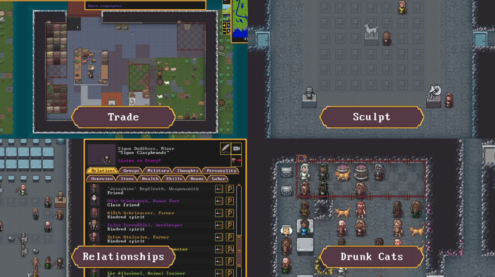

This friction – of making plans that dwarves seem to ignore – is what pushes me out of that mindset of refining pipelines that building games encourage, and to dive into Dwarf Fortress as a story generator. Clicking on one miner to prod at why he just won’t dig shifts focus from the idea of one dwarf as part of a colony of workers, to an individual with incredibly specific wants and needs – down to the favorite type of stone that I let him carve a statue out of to cheer himself up, before it later got toppled in a brawl and cursed someone. C’est la vie.

In most builder games, getting your pipelines right is the point. Difficulty increases as needs or the environment becomes more complex, and you have to adjust for new obstacles and expansions. In Dwarf Fortress, the environment is already endlessly complex – but despite its potential for wild engineering, you can’t pipeline your way out of dwarven autonomy. This nudge of frustration – “why won’t my dwarves do what I want them to” – opens its world to being the narratively expansive game that it’s known for.

———

Ruth Cassidy is a writer and self-described velcro cyborg who is between internet homes. You can find their portfolio at muckrack.com/velcrocyborg.