Recursion

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #159. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

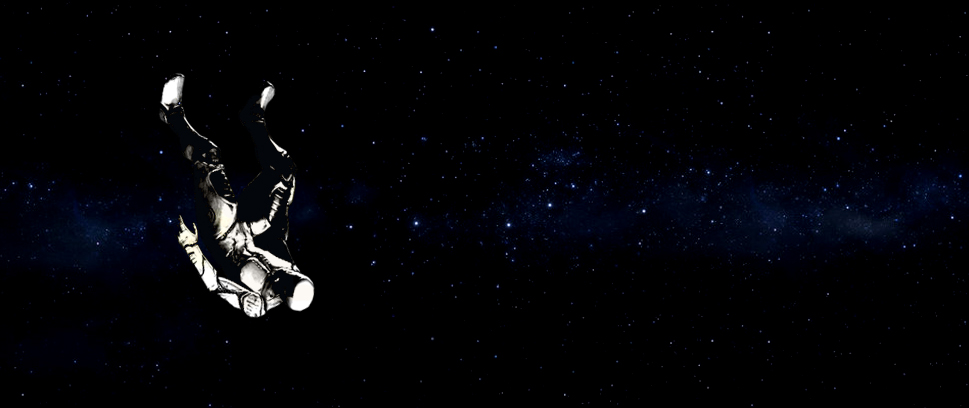

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

Over the December holiday, I finished Ben Lerner’s book Leaving the Atocha Station. It follows an American poet on fellowship in Madrid who writes by combining the words of other poets, and then re-translating them back into Spanish, creating poems that circle around themselves:

I imagined the passengers could see me,

Imagined I was a passenger that could see me

Looking up

Lerner’s narrator, Adam, tells stories by recycling the stories of others. A traumatic incident at a river told to him over instant messenger by a friend becomes his own story he tells to a date, who is horrified as he narrates “sucking on limes” to relieve shock. He lies to his love interests, who become interchangeable, about his parents and his upbringing, and he uses reporting on historical moments as a way to tie himself down to those historical moments. He is a collection of responses to others.

Over the break, I also started playing Dwarf Fortress, a game about avoiding the recurring, inevitable spiral of collapse for as long as you can.

Dwarf Fortress was released in 2002 as freeware, and has now released in an expanded form 20 years later on Steam. It’s a management and storytelling game where you build a community of dwarves and assign them tasks to help grow your fortress. They will do things on autopilot until something breaks, often their psyche, and they are taken by a strange mood and create something. My first dwarf to go crazy created an apricot wooden crutch that they carried around with them, despite never using it. The second, who was unable to pray to their god for too long, created a stool that they then decided had been a family heirloom for generations.

In Dwarf Fortress, I found a different kind of poetry arranged from descriptions about the world. Each dwarf has their own personality, which is constituted by a list of traits such as “disdains leisure” or “not concerned with the feelings of others.” They will do things and then feel emotions. Not only that, they will do things and then remember doing them and feel different emotions. A dwarf talks with a friend and feels fondness. A dwarf remembers talking with a friend and feels fondness. A dwarf gets caught in the rain and then feels frustrated recalling being caught in the rain. One dwarf of mine, a baby, witnessed a murder and then recalled the traumatizing effect of that witnessing again and again, for the rest of her life.

Beyond the reuse of handcrafted dialogue like personality traits, the description repeats itself for the sake of clarity. In Dwarf Fortress, each action and item and their owners are specified down to minute detail, so that you know exactly what a notification refers to. In some cases, this results in a repetition that feels abstract, even emotional. Despite the distance in the description, it can feel almost like an obituary, or an autopsy.

Over the course of Leaving the Atocha Station Adam has two girlfriends, and when one leaves, the other reminds him of the first. Not ever realizing the relationship lets him sit “in the flattering light of the subjunctive,” keeping up appearances first with the first girlfriend and then with the second, neither of whom is actually his girlfriend.

This equivalency only works because Adam himself suspects that he is not an entire person, that he hasn’t experienced art genuinely in his life and that the subject he’s devoted years to, poetry, ultimately means nothing. Adam’s repeating, circling life already resembles poetry. At the end of the novel he’s still considering whether to stay in Madrid or go back to America, but he’s ultimately a ghost in both places, and unable to express a more definite opinion on how art will or will not save his life.

One of the novel’s questions is whether art really impacts life materially, a question I raised in my first column a year ago. Despite the peace Adam seems to find at its close, Lerner’s answer seems to be no. I consider what Dwarf Fortress has to say about the subject. Dwarves make constructions when strange moods take them; their only response to psychological trauma is to create. But what they create is not only random, but it’s not useful: it’s artifacts, the closest thing the game has (besides books) to art. These artifacts provide a baseline for your culture and add to its story. Their creators go back to their regular jobs afterwards.

Is Dwarf Fortress post-modern? It’s certainly random. Seasons rotate back around and you come up against the same scenarios again: the trade route comes once a year, the ice freezes, you can plant again. The dwarves are a lot like the (post-)post-modern novel’s protagonist: they are mostly feelings. Maybe the randomness of their actions is why the descriptions make me so emotional: in a generated world where anything could happen, this, specifically, is what happened. And without randomness and the risk of generating no meaning, everything would feel curated. Instead, I get to see the aftermath of decisions I made without knowing I was making them.

The artifacts seem like an unconscious record of these decisions. Dwarves break under social stress or an individual unmet need and make something that records society as it is now, and when society eventually floods or gets eaten by wolves the artifacts remain. Their lists are their own kind of poetry. They stay when everything living is gone.

Does that make them impactful? I don’t know. But once one of my dwarves, a seven-year-old named Ilral Charmsabres, stopped gathering plants to have the thought that “the creative impulse is so valuable.” I remember that comment when I’ve forgotten most other things about that world, which is in the process of falling apart that I heard so much about before I started the game. I stopped because every season and migration wave started to feel the same. The repetition, so striking at first, got to be too much for me.

The artifacts are still there, though, when I’m ready to look.

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.