Everyone Has a Job: The Future of Silent Running (1972)

“You know, when I was a kid, I put a note into a bottle and it had my name and address on it. And then I threw the bottle into the ocean. And I never knew if anybody ever found it.”

Caught in an unlikely gravitational field between the more philosophical sci-fi of 2001 and the space fantasy of Star Wars is the melancholic Silent Running, newly released on Blu from Arrow Video. Director Douglas Trumbull actually worked on the special effects for 2001 (and later Blade Runner), while the “drones” of Silent Running are obvious precursors to Star Wars’ droids.

Most of the contemporary reviews of Silent Running compared it (usually unfavorably) with 2001, which had come out just a few years before. However, this film has very different things on its mind than either of those. Specifically, Silent Running is a heavy-handed ecological fable about the importance of conservation – one that turns (all too briefly) into a slasher movie where the slasher is our protagonist.

As Penelope Gilliatt said, writing for The New Yorker, “this is sci-fi with the soul of an editorial.” And anyone who complains that modern movies are too didactic probably shouldn’t watch this one, which puts all its theses into the mouth of Bruce Dern’s space-bound ecologist. It seems that in the indeterminate future posited by Silent Running (we can assume that it’s around 2008 or so), all of the Earth’s ecosystems have been completely destroyed, and the only remaining plant and animal life in existence is contained in a handful of geodesic domes mounted on gargantuan spacecraft.

The job of these spacecraft, which are all named after places from which at least some of the ecosystems they carry were initially sampled, is to safeguard these remaining slivers of biodiversity for a future in which the Earth can be reforested – at least, that’s the hope of Dern’s Freeman Lowell. Unfortunately, the film’s conflict kicks off when the ships all receive orders from Earth that they’re to jettison and detonate the domes so that the craft themselves can be put back into commercial use.

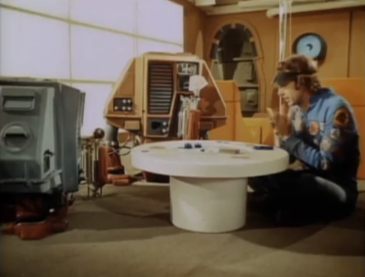

Pretty much everyone else is happy to do so, eager to go home after a mere 6-month stint in space. Lowell, on the other hand, has spent 8 years up there, and he loves the forests and other natural spaces under his stewardship so he, eventually, makes the decision to kill the three other crew members of his ship in order to protect the one dome that remains. He is aided in this only by three robotic “drones,” which he nicknames Huey, Dewey, and Louie – although Louie suffers a “fatal” accident before the monikers are bestowed.

The drones are the film’s most recognizable element. Boxy robots with squat little legs that “[pad] about as if in galoshes” (Penelope Gilliatt again), the drones were played by bilateral amputees, a move that was purportedly inspired by the legendary sideshow performer Johnny Eck, who can be seen in Tod Browning’s 1932 classic Freaks. As the film quickly becomes a one-man show for Dern, the drones are his only companions for much of its running time, and their limited personalities quickly win the audience over, so that the “demise” of one becomes heart wrenching.

Helping along the picture’s attempts at melancholy grandeur is a bassoon-heavy score composed by Peter Schickele, who might be better known as P. D. Q. Bach. Along with the score there are two original songs in the film, both performed by singer Joan Baez – the title song, “Silent Running,” and the really much better “Rejoice in the Sun,” which gets a reprise at the end of the film. Both do as much to sell the film’s tone as anything the actors or production manage.

While Bruce Dern may be front and center throughout the film, and while the drones might steal the show, the star of the picture is probably the ship itself. The Valley Forge is represented both by sound stages and a massive model some 25 feet in length. In proper 1970s DIY filmmaking fashion, the model was a combo of custom pieces and bits taken from various off-the-shelf model kits. After the film’s release, there was an attempt at taking the huge model on a touring circuit, but it proved too fragile, and was eventually dismantled, with several of the domes surviving either in the hands of collectors or, in a couple of cases, in the Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame.

The ship was named, in part, for the aircraft carrier on which several of the interiors were filmed, while others were shot inside aircraft hangers. While the design of the domes was inspired by the Climatron dome at the Missouri Botanical Gardens, the plan was to film the dome interiors in Milwaukee’s Mitchell Park Domes. However, doing so proved to be out-of-budget, and the interiors were instead recreated on soundstages.

In perhaps the film’s greatest irony, the ship in question is supposed to be an American Airlines space freighter – a bit of particularly conspicuous product placement in what is, ostensibly, a film about the evils of capitalism, at least where environmental causes are concerned. It’s not the only time the film’s message feels oddly out-of-joint, either.

We’re obviously supposed to side with Dern’s character, even while he kills some people and, eventually, realizes the tragedy of his actions. However, when he’s giving his big speech about how bad off the world is, the other crew members give some pretty good-sounding contradictions. “There’s hardly any disease,” they say. “No poverty. And everyone has a job.”

Sure, that last one is very capitalist of them, but it’s tough to argue with no poverty and hardly any disease. How, exactly, there’s any air on a planet that doesn’t have a single tree is never addressed. Indeed, the utility of the natural world is never on the table. The world seems to be getting on just fine without it, where utility is concerned. It’s the beauty and wonder of nature that’s important.

But there’s something else underlying that, too, and it’s there in Dern’s character’s first name: Freeman. Like a lot of sci-fi dystopias from this era, the concern here seems to be that what we’re going to lose is individualism at the expense of having everything else provided for us – itself a uniquely capitalist sort of dystopia, and one that seems hopelessly naïve in a 2022 where we probably have entirely too much individualism and not nearly enough anything else.

“On Earth,” Dern says, “everywhere you go, the temperature is 75 degrees.” (Which also doesn’t sound all that bad, frankly.) “Everything is the same; all the people are exactly the same. Now what kind of life is that?” While lamenting that there’s “no more beauty” and “no more imagination,” he follows this up with “no more frontiers left to conquer.”

If anything undercuts the environmental and anti-capitalist message of Silent Running, it’s this insistence upon a very American breed of rugged individualism. “You’re a hell of an American,” a voice over the radio tells Dern’s character, when they think he’s about to die a heroic death. “Yes,” he muses to himself, “I think I am.”