An Hour Making Games in the Belly of Demonicon

“Give me time to undo what I have done. Give me a year – a month – a day – an hour! Give me this hour’s end, that I may undo what I have done!” – William Butler Yeats

What is an hour, really? The division of time into small pieces of each day is very, very old. The water clock was used in China in at least 3,000 BCE and in Egypt in at least 1,600 BCE. An Egyptian sundial from 1,500 BCE split the daytime into a sunrise part, 10 daylight parts, and a sunset part. More precise forms of timekeeping developed over, well, time. When cities started to connect with each other via regimented systems like railroads and shipping routes, they relied on hours and even minutes.

Time only got smaller from there. P.V.H. Weems invented the watch that kept seconds, which he made for use in navigation but also revolutionized competitive sports. Today, scientists can divide one second into tiny little pieces that push the small end of the metric system. And if you’re in a waiting room, expecting a pizza, or counting down to a meeting where “we need to talk,” you know how long an hour can really be.

I asked folks what they could get done in an hour. Suggestions included writing letters to voters, planning for upcoming D&D sessions, eating “a ton of fries,” watching two episodes of Pee Wee’s Playhouse, and my particularly ambitious friend Ravi: “Exercise, shower, and be ready to leave the house.” (Weird flex but ok.) When you’re talking with a treasured friend or partner, an hour can feel like just a blink. But what if you’re making a game?

———

Just over a year ago, I joined a maker community called Strange Pact. One of its founders, Hyacinth Nil, is a game developer and musician who has run a Halloween marathon stream called Demonicon for the last three years. This time, they planned a one-hour game jam and asked who wanted to join. I make short text games and kinetic stories, and I’m used to writing against crushing deadlines while working as a freelance writer. It sounded like fun.

“I was kinda super busy when it was all coming together so I didn’t really ask a lot of questions,” participant flan, a game developer and instructor, told me. “I just knew it was going to be a short game jam during the stream and I was down.” Matty had a more concrete thought process: “Most of the things I make, if they actually end up finished, take a frustratingly long time to actually make into anything worthwhile,” they told me. “It seemed like it could be some good fun with the people there, and a different challenge than normal.”

Misha V. summed up how I felt, too. “I wanted to sign up because I’m usually frustrated with how I get stuck in the weeds with a lot of projects and I wanted more fully complete stuff under my belt,” she told me. “I wanted to see how small I had to scope a project to get it done in a super tight time frame. Additionally, I wanted to see what a full focused hour’s worth of gamedev looked like for me.”

Some folks decided to sign up on the day, or even later. Artist and software engineer Cameron joined Demonicon to perform – they use code to create live art and music in an improvisational way – and wound up in the jam by accident. Artist and developer Quinn K. joined ten minutes in: “I saw people prepping for it in the Discord’s voice chat and realized, ‘Wait, I’ve made a game in a day once recently. With my toolset I could feasibly make one in an hour.’”

One thing that struck me about the group is how different all of our skillsets are. I do just enough coding to glue my writing together, but some of the others are professional game developers and other kinds of full-time coders. Folks worked in Godot and Unity alongside text game tools Twine and Ink (my choice).

So how did people decide what to take and what to leave behind as they made their plans? For my part, I decided to take an existing text file and strip it to its skeleton so I could fill it back in with new content. I planned for seven very short “chapters,” and then it occurred to me that this was also the number of non-Earth planets in the solar system. I decided to combine astrology and very simple astrophysics to describe how a character would die on each of those planets.

Image from https://www.astrology.com/planets

“I focused mostly on there being something to do in the game. Polish became second, quality and coherence of writing became second,” Quinn K said. They used default assets and “a smelly song lying around,” a benefit of being one’s own composer. “I guess I chose not to focus on mechanics and more on creating a mood [or] environment type experience,” flan said. “Hacks, all of the hacks,” Matty said. “It didn’t matter if it’s good code in the long run. I really couldn’t afford to take much time with textures or modeling, so I ended up budgeting just enough time to make a single model, one texture and one animation.”

Misha V. took the opportunity to try something different. “I chose a system that I knew was as simple as possible so that I could prioritize content over mechanics,” she said. “Since, usually, I spend a LOT of time building mechanics and then don’t leave myself enough time for content.” Cameron said they barely had to adjust, because “it’s a really similar mindset” to performing. “I feel like I optimize for getting something fun or interesting as quickly as I can,” they said.

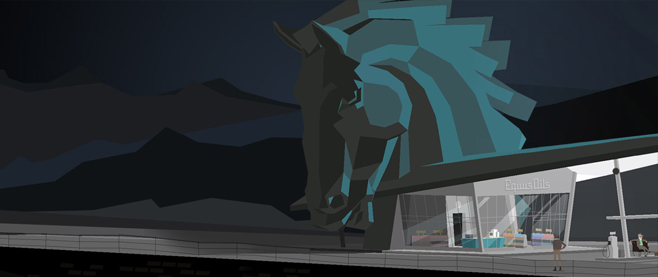

Did those plans work out? Mine did – I finished the hour with an 800-word file that covered all seven planets and a very short conclusion. Cameron made a neat cloud or smoke animation that follows the mouse. Quinn K. said, “Kind of, kind of not?” and explains that even a “non-serious” project can have issues with wording and consistency. flan said, “Yeah, and I think it was easier to hit that goal [because] my plan wasn’t super specific.”

Matty missed “one line of code” that prevented their core mechanic from working, but left a working walking (bouncing?) simulator of sorts anyway. And Misha V., the other text game writer, said Twine helped her connect the pieces smoothly in a limited time. “[A]ll I had to do was write and write,” she says. “But even with the really limited narrative I planned, it was still tight at the end.”

The hour passed really rapidly. Like, on a scale of dentist’s waiting room to life-changing conversation, I couldn’t believe how much fun I had while under a large time burden that grew steadily more crushing – “consensually,” Syn joked on Twitter – because of the good company and fun shared goal. Everyone I talked to agreed they’d do the hour-long jam again, but Quinn clarified, “The crowd definitely has to be right, though.” Indeed, a challenge shared is a challenge halved.

———

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and enthusiast of just about everything. Her favorite topics include islands, narratives, cosmology, everyday math, and the philosophy of it all.