Evil in Residence

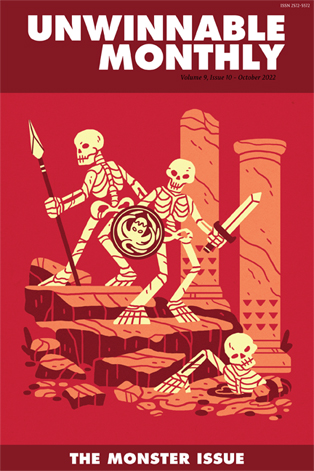

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #156. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Finding deeper meaning beneath the virtual surface.

———

It was a few years past the original PlayStation’s release date before our family could afford to buy one, so my brother and I would often play early PS1 games at the houses and apartments of neighborhood friends. In our apartment building there was a pair of brothers who were about as old as us and who lived just one floor below. My brother and I would spend hours at their place, especially during the long, lazy days of summer, when nothing was expected of us besides needing to leave the house (and our parents in peace).

Probably the most memorable moment over the many years we spent playing games there or watching the same movies over and over on their unlocked cable box, was the day the older of the two brothers came home with a certain new PlayStation game tucked under his arm. Beneath the hard plastic surface of the jewel case were the tall red letters of the game’s title: RESIDENT EVIL.

We didn’t have much of an idea of what we’d be in for, based solely off of the nonsensical title and the generic soldier man surrounded by shadows just beneath it. So, we sliced apart the shrinkwrap with a fingernail, popped open the case and snapped the disc firmly onto its mount in the console bay. We laughed and cracked jokes during the straight-to-video-lookin’ introductory cutscene, but then grew nervously quiet once our troop of special agents made it within the mansion proper, shutting the door behind them and thus transitioning from grainy, soft bodied actors into beings of hard blocky polygon instead. These new depictions seemed more real in spite of their clunky shapes and accompanying hammy voice actors. They seemed like they could be hurt or maimed by way of our actions, or lack thereof.

We navigated cautiously through the first few rooms, empty of anything besides scenery, which our characters would clumsily bump and slide against, victims to our poor understanding of the game’s unorthodox, fixed camera and its tank controls. The setting was unsettling, quiet. Our characters’ footsteps drummed loudly against the mansion floors, boots marking a steady bass against the hardwood, a high-pitched timpani treble against the marble. Whatever was surely skulking offscreen would be certain to hear us as we made our halting progress deeper inside.

It wasn’t long before we discovered precisely what would be waiting for us in this mansion. The brother who had bought the game had been the one piloting one of the game’s protagonist, Jill Valentine, so far. He led her down a darkened servant’s passageway, long and claustrophobically narrow. His Jill rounded a corner and in doing so triggered the camera change which revealed what was on the other side. This scene before us was utterly monstrous: a hulking form was bent over a combat gear-clad corpse, one of our own. The thing’s pixels and shading were a mess of brown and green, all gross, all wrong. It was something prehistoric, from the swamps, of the earth. In stiff, jerky movements its head bobbed over the body, moving with animalistic fervor.

The camera took over at this point, as if to help us out in our horrified, frozen stupor. It drifted closer to the creature’s back, closer, as if to see, to see what it could be possible doing to that poor rigid corpse. As the camera slowly angled up, revealing a diseased-looking skull, furrowed deeply with cracks and veins, the thing’s head bobbed again, one final time. Through the television’s speakers came a sharp crunch, like bones breaking, like a foot cleaving through a light crusting of ice into a frozen lake. On screen, a pool of blood quickly began to pool out from the creature’s hidden victim, spreading rapidly toward our feet. Before we could react, however, the creature’s head lifted, and turned, finally altered to our presence.

Large, slick yellow eyes, poking out from a ghastly brown skull turned and stared directly at the camera. It didn’t feel like the monster was looking at our character, but at us, us four, quaking boys gaping helplessly at the TV screen. The brother holding the controller let out a frightened yelp and tossed the thing away like it was on fire. Chaos immediately followed. Our character stood stock still on the screen in front of the monster, which slowly got up, turned and began ambling, inevitably toward us.

“Someone take over!” The boy who’d just abdicated responsibility not-so-helpfully commanded. The controller sat between us, a horrid little pain box, there to mete out punishment for whosoever dared pick it up. I made the brave or stupid decision to be the next supplicant and I reached out and grabbed it, its surface warm and slick from the sweaty hands of its previous operator. By this point, the beast had already halved the distance between us, its outstretched arms patiently reaching out for us. I jammed my thumbs against what I hoped were the right buttons, having not been allowed the buffer of the game’s tutorialization moments. My Jill slowly rotated left, then made a quarter turn to the right, then backed up, directly into the thing’s waiting arms.

It sunk its jagged fangs into the neck of my character and we all helplessly shrieked with terror. I cajoled and tugged at the controller to little avail, I could only wait until the creature was done, finished with me, sated. It finally released us, and Jill, bloodied, staggered back and away. Hitting pause brought up the menu screen showing the game’s grid-like inventory next to a small heart rate monitor which pulsed out a threatening orange. I saw that Jill held a gun in her inventory and worked out how to equip it. Closing the screen revealed the gun had appeared in Jill’s hands, so I brought it up and fired. The first shot flew wide of the beast’s grinning maw. Before I could fire again it had again flung its impossibly long arms around us. Once it was done with us I checked again, the heart rate monitor now glowed a weak red.

We were lost. We had thought this was just another ordinary videogame, another careless stroll through some colorful world full of coins and spells and power ups. Another power fantasy with which to show off our petty prowesses to each other. Resident Evil is decidedly not this. It’s a Hellraiser puzzle box; an invitation to partake, to play along, only to realize (too late) that the controller itself is a portal through which the game itself can reach out and draw its horrifying tithe. This was why none of us wanted to touch the controller. None of us wanted to feel that panic, burn our fingertips on that live wire. Which is why we abandoned Jill, in that moment, to her fate; to the first monster in a game lousy with them. We wouldn’t try again for weeks, couldn’t be persuaded by the remorseful purchaser of the title to give it a try once more, to dive once again through those slowly creaking double doors, back into the frightening darkness.

———

Yussef Cole is a writer and a visual artist hailing from the Bronx, NY. He makes images for the screen and also enjoys writing words about the screen’s images.