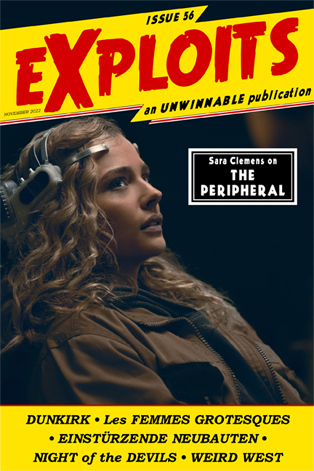

The Peripheral

This is a reprint of the Television essay from Issue #56 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the Television essay from Issue #56 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

Amazon Prime’s new sci-fi series is a tale of two timelines of the not-so- and very-distant varieties. The first is early 2030s North Carolina, where a hard-twanged young woman lives in the house she probably grew up in and cares for her terminally ill mother while working at a 3D print shop. She also occasionally helps her Marine veteran brother out with his side hustle assisting wealthy gamers in incredibly immersive VR videogames. They hire him to help them level up, virtually passing him the controller to get them through the hard parts. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Burton, her brother, is good, but Flynne is better. So good in fact, she barely needs to try. The future-gamer bros hire Burton to get them through the tough parts but when the tough really gets going it’s Flynne he calls in for the assist, and she rolls her eyes before pulling a headset over them and absolutely annihilating some Nazis laying siege to a rustic European barn in WWII. She even manages to save the sheep.

It’s through this gaming prowess that Flynne’s introduced to a brand-new, cutting-edge simulation of a post-apocalyptic London in 2100. Everyone in this sim rocks fire ‘fits, the social gatherings are extravagant, the motorcycles go fast and the hits Flynne’s avatar takes feel really, really real.

That’s because they are, of course. Flynne’s mind is actually being projected into a robotic avatar made to her measure in a time 60+ years after her own. How this time travel of the mind works is explained away with the hand wave-y term “quantum tunneling” (one might need to cross-reference the William Gibson novel the series is adapted from to grok the harder sci-fi elements) but it quickly becomes apparent that the denizens of the very distant future have no trouble directly influencing the timeline closer to our own. And it’s in the Blue Ridge Mountains in 2032 where we find the show’s emotional core. Flynne’s hometown is so small-town that much of the future version of it seems to lag slightly behind our own present, as evidenced by a complete lack of social media that is both bewildering and reason to live in hope.

2032 and 2100 each have a big bad villain, but only one moves through his dusty domain with a recognizable monstrosity. There are people Flynne connects with in both timelines, but in London she’s just a mind connected to a well-appointed robotic body – one that can feel pain, yes, and so we must assume the possibility of the opposite – but it’s only in North Carolina that Flynne and her compatriots feel like people of flesh and bone. Here’s hoping the London segments don’t stay so bloodless.