On Being Chased

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #156. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

We are what we’re afraid of.

———

It’s a nightmare so common as to almost be universal: you’re being chased. Maybe the thing chasing you has a face, a shape, a physical presence. Or maybe it’s something you cannot look directly at, but you know that it’s right behind you. And no matter what you do – how fast you run, how many doors you lock behind you – it will continue to follow you. And eventually, it will catch up.

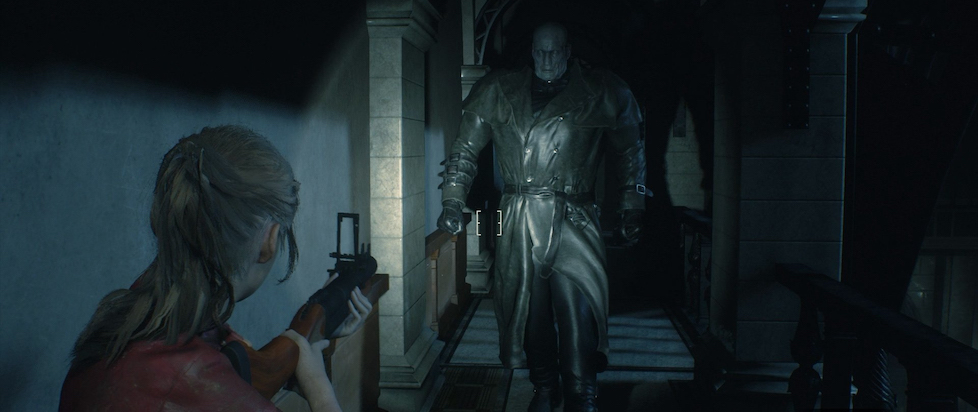

The trope of the constant pursuit has populated horror films for decades, and is particularly prevalent in the slasher film; the killer always finds their victims in the end. Since it’s such a popular conceit, it only makes sense that it makes several healthy appearances in survival horror videogames. The most famous examples come from the Resident Evil franchise, which uses the mechanical device across several games, from Mr. X in RE2 to Nemesis in 3 to Jack Baker in 7. With these enemies, the only course is to flee. While they can deal damage to you (and often hit hard enough to kill you in short order), you cannot harm them in any permanent way. In some cases, you can sink a substantial amount of ammo into them to stun them temporarily, but you cannot kill them. No matter what you do, they will follow you.

This idea, of being pursued by a force outside of your power to destroy, is especially scary in videogames because it disrupts the central power fantasy of a lot of action game experiences. In many videogames (including some entries in the Resident Evil franchise, like RE4), the player acts as a kind of apex predator – with minimal management of ammunition and some skill in aiming, the player can mow down enemies with relative ease. And as enemies get tougher, so do you. The central idea is that there is no challenge you cannot overcome. But the unkillable monsters of games like Resident Evil douse that fantasy. You cannot overcome. Instead, you will be overcome.

Being in a position of very little power to control your situation is a classically anxiety-inducing scenario. It happens in our daily lives, with our jobs, our families, our futures. Videogames can often be seen as an escape from that uncertainty, into a world where the player holds ultimate power – as long as they follow the rules of the game, they cannot help but triumph. With enemies like Nemesis, Resident Evil turns that narrative on its head. It reminds the player that not only are they not in control of the situation, the idea of control is an illusion. Every choice made, every button pressed, is nothing more than feeding input into a limited, deterministic system. The actions of players and their success are inherently limited by the code of the game itself – even open-world experiences are ultimately finite and dependent on scripted encounters created by the developers. While many games try their hardest to hide the fact that players have never had free will or any particular power to alter the experience of play, horror games use these monsters to put that idea at the forefront. And it works, because it is terrifying.

Ultimately, then, these monsters are more than bundles of code: they are a concrete reminder of the lack of control that we have over our own lives. Throwing the power fantasy of the general action gaming session out the window shows us that this, too, is something we cannot manipulate; we are powerless to do anything but respond. And even though in most cases the game eventually provides you with a means to kill this once unstoppable juggernaut, the player is left with the fear of being followed by something much more powerful than themselves.

So, my ending questions are many, but they boil down to this: Is it actually the monster that we fear? Or is it what the monster represents? We are powerless against all the fundamental truths of our lives: the passing of time, the inevitability of death. We can run as fast as we can, or we can lock ourselves away in hiding. But death finds us all in the end, no matter what we do, whether it takes the form of old age, illness, accident, or a seven-foot-tall mutant in a trench coat. When games like Resident Evil force us to reckon with these immovable objects as monsters, it also makes us consider the unstoppable forces of time in our lives, and how at the end of the day we don’t really get a say in how or when we go out.

And that’s maybe the most terrifying idea of all.

———

Emma Kostopolus loves all things that go bump in the night. When not playing scary games, you can find her in the kitchen, scientifically perfecting the recipe for fudge brownies. She has an Instagram where she logs the food and art she makes, along with her many cats.