Flying Shop of Horrors

Whispers abound of a suspicious figure haunting the skies of Breath of the Wild‘s Hyrule. Lurking above in his dingy balloon, only making himself known in the dark of knight when he might peddle his wares and get up to who knows what kinds of unusual activities. He’s different! He’s unknown! He must be dangerous! Such are the sentiments conveyed by a few NPCs regarding Kilton, the entrepreneur behind the flying shop, Fang and Bone. This month at Unwinnable, monsters are taking center stage, but as Hyrule’s most enthusiastic monsters fanatic, Kilton would likely argue he knows more about them than any of us. However, Kilton’s desire to celebrate and spread his love of monsters is so ensnared in economics and moral dubiousness, perhaps the wary townsfolk of Hyrule’s warnings best be heeded after all.

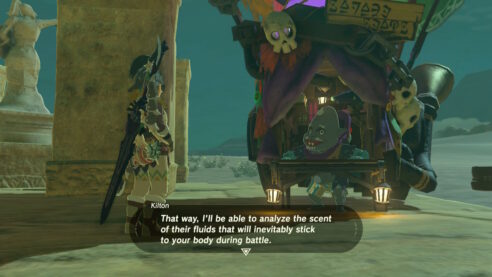

In his enthusiasm for monsters Kilton exhibits all the symptoms of a Twitter stan. Not only is he a fan of Hyrule’s bokoblins, moblins, lizalfos, and lynels, but he wants other people to share in his fandom. However, stanning also means becoming irrationally combative without prompting whether in defense of his beloved fixation, or in insisting he knows more about the object of his desire than anyone else. Unlike Nicki Minaj’s barbs or LOONA’s orbits, Kilton isn’t protective of his fixation’s physical safety. In fact, he encourages you to hunt Hyrule’s monsters and bring him their horns, teeth, or organs for his collection and crafts. Whether or not these spoils are integral to the crafting of his wares at Fang and Bone is ambiguous. One would assume Kilton grinds up these body parts to prepare his “monster extract” which Link may use to season food. But one aspect of Kilton’s business is chillingly unambiguous. The very thought of it sends goosebumps up my arms and my mind tumbling into unending terror. In the villain’s own words:

“I just love monsters so much that I turned them into money!”

Thus confesses the possessed, revealing that his body is a pitiable host to one of the most fearsome of archdemons: capital. For each monster part you bring, Kilton will credit your account with “mon” in various amounts depending on what you bring. The process by which he converts monster parts into mon is unclear, but the result and its implications are horrifying. Kilton’s desire to study and celebrate monsters has been perverted into a desire to commodify them both into consumer goods for sale at his shop, but also into the very currency used to purchase those goods! Objectification and commodification compounded. Like a grisly Spirit Halloween where the entrails are real, Link brings Kilton the flesh and viscera of his beloved, he converts them to currency, and Link may then buy masks resembling the very creatures which have been slaughtered to begin with. Using these masks as disguise, Link can more safely approach the beings being impersonated; all the better to slay them and facilitate this gory supply chain. Like the balloon in which Kilton dwells, fanaticism, embodiment, and economics have been stitched together to loom dreadful over all.

What’s worse, Kilton is commodifying sentient creatures who possess some degree of culture. What can be gleaned through observation of Bokoblins, for example, is that they use tools and weapons, communicate enough to sound warning calls to each other, and express themselves through dance. Lynels are also intelligent enough to see through Kilton’s masks. As if hunting creatures for sport with no ecological agenda wasn’t grim enough, these are creatures with an unignorable degree of personhood whose bodies and bones are harvested in exchange for recreations of their own desecrated flesh. Sadly, though their personhood cannot be denied, it is unsurprising that Link and the player cut them down by the dozens.

For Breath of the Wild the personhood of Bokoblins, Moblins, and the like is extended only as far as that of prototypical fantasy baddies à la Lord of the Rings or Dungeons & Dragons; enough quirks or mannerisms to be interesting as foes, but not so nuanced as to disrupt the fantasy wherein the player may “kick down the door heroically and kill the bad guy without interrogating what that means.” Calamity Ganon is an unquestionable evil in Breath of the Wild’s Hyrule and his minions are framed in kind. The player, through Link, need not dwell on the morality of slaying these people, as they have been positioned as worthy of hunting by the game’s worldbuilding. Though other game franchises like Monster Hunter also task the player with carving away at monsters’ bodies to fashion weapons and equipment, there is no moral imperative or failing in doing so. Neither the shallow trappings of ecology in Monster Hunter nor the meta chastisings of Undertale may hinder the player in their sport. Especially when the blood moon rises after every seven days of game time passes to resurrect all the monsters who have fallen. The hunt begins anew and Kilton’s desire to study and celebrate through literal capitalization is fed.

Kilton is an outcast who is looked at with suspicion by those who do not know him. Weary soldiers and gossiping travelers are wrong to situate him as a pariah based solely on the non-normative way he operates under cover of night. It’s not his adherence to social norms, but the twisted ways he acts on his desire which should be feared. Like Little Shop of Horrors’s Audrey II, feeding his desires only escalates his hunger as he yearns for samples of larger, deadlier game. Unlike that mean green mother from outer space, Kilton doesn’t need monster parts to sustain himself. His desire may have been born of a thirst for knowledge and an affectionate fascination, but it has been ensnared by the tentacles of capital and commodity. That way lies only abstraction and exploitation. Today Kilton handcrafts his masks with love. I fear there are only so many blood moons until the shelves of Hyrule’s autumnal costume and decor stores are lined with polyblend socks adorned with bokoblins and keese. Check the lining for lynel sinew.

———

Trevor Richardson is an essayist and lit mag editor. They’ve written about Nier (and other games, they suppose) for Uppercut, Gayming Magazine, and AIPT. They can be found on Twitter @Brisuuve.