1943

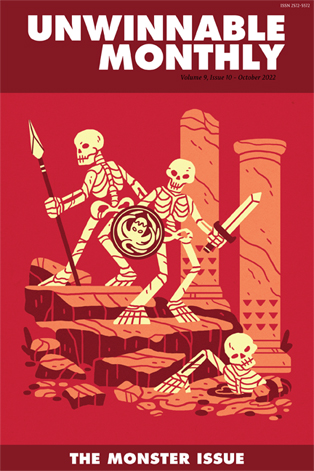

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #156. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

To create a zombi, a bokor must separate the flesh and the spirit. From then on, the new being is subject to the will of its maker/killer – at least until Baron Samedi intervenes.

I Walked With A Zombie follows a nurse hired to look after a plantation owner’s wife, who has been in a not-quite-coma for an extended period of time. As the title suggests, it turns out that the woman has been turned into a zombie.

Tourner’s vision of the (fictional) island of Saint Sebastian is a fascinating one. Rich white communities live amongst the descendants of former slaves, many of whom were (presumably) enslaved by the ancestors of those same wealthy white people. And the majority of those Black people we see work on the plantation of the wealthy white Rand/Holland family at the center of the tale.

We are repeatedly reminded of the violence that was required to construct a place like this. Almost every time that the naive lead Betsy Connell (Frances Dee) talks about the beauty of this place, someone reminds her of the violence of the flip side, whether it’s from her beloved gloomy Paul Holland (Tom Conway) or the Black people living on this island who are descended from the slaves that built it. We are also reminded of how pathetic these colonizers are. Holland’s heightened upper-class Englishness and his brother Wesley Rand’s (James Ellison) charismatic cowboy act are both undermined by the petty shittiness of their characters. Instead of grand masters of the new world, they feel like squabbling children desperately holding onto the power of their ancestors.

Back to the zombie itself, I don’t think there is a singular signifier you could apply and capture the whole picture. This is not helped by how, alongside Tourner’s critiques of these historical violences, he is also very clearly leaning into the fetishistic fascination with vodou that became particularly sharpened in the wake of the US occupation of Haiti. That is perhaps most clearly embodied in Victor Halperin’s White Zombie, since both films show a struggle between two white men over a beautiful woman leading to her zombification.

However, what makes this film more interesting than White Zombie is that the threat to the revered white femininity comes from within. Sure, the tools of this violence are foreign, but the perpetrator is very much of the white imperial class, and it’s a pretty sharp portrayal of the inherent self-destructiveness of this sort of need to conquer and possess. And crucially Tourner does not doubt the vodou in the way that other contemporary works do. While there is no certainty, the best explanation we are offered is that Mrs. Rand leaned into the power of the divine (or at least the magical) to cause the zombification – something Edith Barrett sells in her performance. And how small-minded could you be?

What kind of person does it take to finally connect with power so much greater than yourself and to use it for something so small-minded? How do you see that the world is bigger and more full of mystery than you had ever imagined and yet still your purest impulse continues to be to subjugate? That is the rot at the core of the colonial psyche that this film skewers.

Of course, even with the imperial violence turned inwards, it is still first and foremost aimed at subjugating the Other. At the same time as this film was shot, Haiti was still paying France as punishment for freeing themselves from enslavement. These indemnity payments had to be paid while huge swathes of the Haitian population starved and played no small part in the social and economic turmoil that the island nation experiences to this day.

To create a zombi, you have to kill the victim first.

In Langston Hughes’ Freedom Plow, he tracks a history of labor and freedom in the US, how the promises of universal freedom that were so evidently false and yet Black Americans still held the will to make them manifest. The plow becomes a metaphor for the enduring power of Black labor. At the same time, Black people across the globe were going to war against the fascism enabled by their colonial masters, and History would reward them by deliberately forgetting their existence. But the steady beat of the plow goes on and on and on like a throbbing heart. As long as the beat goes on, we remain alive and can’t be made subject to complete control – there is always the chance that revolutions wait in the wings.

That is where power lies – in the swings of the plow.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer. You can find her Twitter ramblings @naijaprince21, his poetry @tayowrites on Instagram and their performances across London.