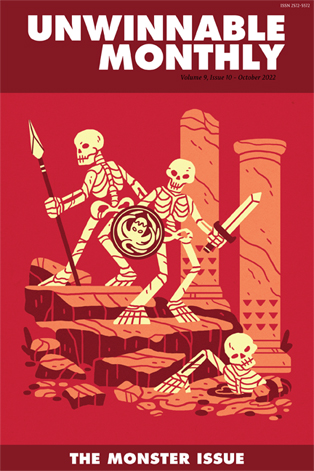

On Monsters and Ourselves

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #156. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Reframing the boundaries of what is seen and unseen…

———

As a kid, I used to sneak around in the horror movie section of my local Hollywood Video while my Dad looked for British period piece dramas. I was entranced by the horror film’s cover art. The more grotesque or monstrous, the more likely I was to pick it up. It was through this process that I found out about movies like A Nightmare on Elm Street, Halloween, Friday the 13th and Hellraiser.

What set Hellraiser apart from the rest was that Pinhead didn’t exactly scare me, if anything, I found his design pretty cool. On the VHS for the first film, the tagline read, “Demon to some. Angel to others.” The duality it presented intrigued me. I wanted to know what the golden box in his hands was and why he had pins nailed all over his head. His design was unsettling, but also a bit alluring too. That’s always been the ethos of the Hellraiser franchise, it’s most comfortable in pushing the viewers to cover their eyes while also asking them to take a peek at whatever gnarly laceration is taking place on the screen.

It wouldn’t be until my early 20s that I finally sat down with friends and watched Hellraiser. I was floored by it. The gore throughout the film is spine-tingling, and Pinhead and his fellow Cenobites are incredibly unique in their design. But the two things that stuck with me the most was how little the Cenobites are featured in the movie, and that Pinhead really isn’t a villain, at least not in the typical horror film sense. While Pinhead’s horror genre compatriots were terrorizing teens for simply living, he and the Cenobites existed in a more liminal space – monsters to some, saviors to others. While harrowing in their aesthetic, there was a somber aura to them, one that made me feel a bit bad for them compared to the people the terrorized.

In the Hellraiser mythology, just like Clive Barker’s other horror icon Candyman, the Cenobites must be willingly summoned. They are extra-dimensional beings who cannot discern pain and pleasure, they simply respond when beckoned by human desire. They reside in Hell and are brought to Earth through people solving a puzzle box contraption known as the “Lament Configuration,” an alluring golden device that would probably tempt anyone that came across it.

What becomes clear by the end of the first film is that humans and their untamed desires are the true monsters. The Cenobites are simply the messengers that deliver what users of the Lament Configuration want – which usually entails sadomasochistic ends.

In a sense, the Cenobites become a reflection of our interior lives, a darker voice we tend to bury deep inside. This becomes clearer in the second foray in the franchise, Hellbound: Hellraiser II, which follows the protagonist of the first film, Kirsty Cotton, dealing with the traumatic aftermath of the death of her father and surviving an encounter with the Cenobites.

Much in the same vein as the first film, for the majority of the first half of Hellbound the cenobites are largely absent. Instead, the focus is on Kirsty and her struggles to stop the true villain of the film, Dr. Philip Channard, who co-founded a famed mental institute where he secretly uses patients as guinea pigs in his research of the Lament Configuration. The draw of Hellbound for fans of the franchise is that it shows the viewer what Hell looks like in this universe – a maze-like otherworld that morphs and changes based on whoever has entered it.

I was mostly interested in watching Hellbound as an experiment before Hulu’s Hellraiser reboot dropped. The trailer for the reboot seemed to veer into Cenobites as slashers, which to me is the antithesis of the ethos of the characters.

Something that is lost in later entries in the franchise is the indifferent positionality that the Cenobites embody within the world. Instead, the sequels transformed them into your typical horror film villains that come back each film, feverishly trying to top their previous cinematic murderous rampages with new kill set-ups.

I was pleasantly surprised to find that Hellbound doesn’t take this approach, but instead feels like a true continuation of the first film. Instead of a horror film in the typical sense, Hellbound turns more into an adventure film as Kirsty attempts to stop Dr. Channard. The typical killing spree you expect throughout these monster-driven horror films happens, but it is more of an afterthought to the character dramas unfolding in the forefront. If anything, the Cenobites take on a role of perplexed bystanders to the human triflings unfolding on their home turf. In Hellbound, Pinhead and his “Gash” (essentially his gang of monastic followers) don’t kill anyone, in fact, they are killed by Dr. Channard after he is transformed into a Cenobite himself.

Hellbound forces us to continue deconstructing what exactly monsters are and how monstrosity largely hinges on perspective. Hell in the Hellraiser universe reflects back to others what they struggle with the most. It’s a fluid space that changes as our own sense of self does. Hellbound also attempts to further humanize the Cenobites by showing the viewer that they too once were human. It tells us that the Cenobites aren’t bloodthirsty demons looking to kill any chance they’ve got, instead, they are beings that force those that summon them to face their inner yearnings.

I’m stuck on the feeling that this franchise, especially the first two entries are able to make me feel. After I’d watched Hellraiser for the first time, I had to check out the novella that Clive Barker wrote as a proof of concept for the film, The Hellbound Heart. Buying a copy of the book felt a bit scandalous, a little dirty even. Carting it around town, into classrooms and over to friends’ houses felt a bit like revealing some of my own macabre desires.

The cover of my copy of The Hellbound Heart is a skinless man with a deadened stare. Looking deeper you quickly realize that not only is the man skinless, but his face is comprised of a naked man sitting cross-legged surrounded by grey beings who are grasping at him in a sensual manner. It’s a piece of artwork that equally disturbs and entices you to look further, and to me, that’s what the best fictional monsters always are – a dialogue between what we fear and want, transformed into confrontational form.

———

Phillip Russell is a Black writer and podcast producer. His writing explores the intersections between pop culture, Blackness, and our connection to land and identity. Follow his work on Twitter @3dsisqo.