Monsters Built by Human Hands

This is an excerpt from a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #156. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Presumably, someone built the town of Silent Hill. It looks not too dissimilar from the place I grew up; few distinct features on first blush and easy to find familiar. There are stores, a hospital, a church, all abandoned now for seemingly no reason. The town itself isn’t ontologically bad, cursed or putrefied; it is, however, not meant for people to live in. Anyone who doesn’t have a reason to be there is no longer there. Someone probably built Silent Hill, but it feels like it always has been. It’s the body of a monster, each building a mouth ready to bite down and each apparition shuffling through their halls like grasping fingers clawing at those who enter.

Everyone who comes to Silent Hill is there for a reason. The town makes sure of it.

No discussion of the Silent Hill games is complete without looking closely at how each game uses its setting. The place that each character in every game finds themselves and their specific path through the twisting metal and flesh corridors is deeply personal and reflects their trauma back at them. This extends beyond the narrative and is intertwined deeply with each game’s level design and monster design. While the first Silent Hill game hadn’t quite found its footing regarding how intimate and specific to make the narrative, the second game in the series sets out to callously observe and systematically dismantle its main character, James Sunderland.

By almost all metrics, James is a terrible person. He murdered his terminally ill wife, whilst lusting after all manner of different people as his attraction to his wife deteriorated. I’m not going to try to argue that he does or does not deserve what befalls him throughout the course of the game, but rather how his awfulness is manifested. Lakeview Hotel as a videogame level is specifically focused on James, his history and what he has done. What follows will focus exclusively on the hotel and how it functions, both as a compelling videogame level and something akin to a monstrous final boss.

Before getting into the nuts and bolts of how the level works, it’s worth noting that Lakeview Hotel is specific to Silent Hill 2. It might exist in the diegesis of other games in the series, but is never referenced or shown. It is specific to James and his story, as a location where he and his wife Mary stayed while vacationing in Silent Hill. It is punishment made manifest for James, as his deeds are etched into every wall and every encounter with an enemy; the monsters serving more like fingers of the space than individual actors in their own right. This general structure is not unique in horror; haunted hotels are fairly commonplace in our cultural consciousness. Stephen King’s book The Shining and Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation are almost blueprints for this kind of story; a terrible man stays in a hotel, his underlying badness is exploited by the hotel (which slowly reveals itself to be akin to a living creature, watching and feeding on the main character’s trauma). Silent Hill 2, while not outright discarding this pattern, changes it by implying that the hotel, or at least this version of it, does not preexist James, like the Overlook Hotel from The Shining has existed before every caretaker as a malevolent presence that harms many, if not all, who stay inside it. The instance of the Hotel that appears in Silent Hill 2 was constructed for James by the town, as a vision of Hell just for him.

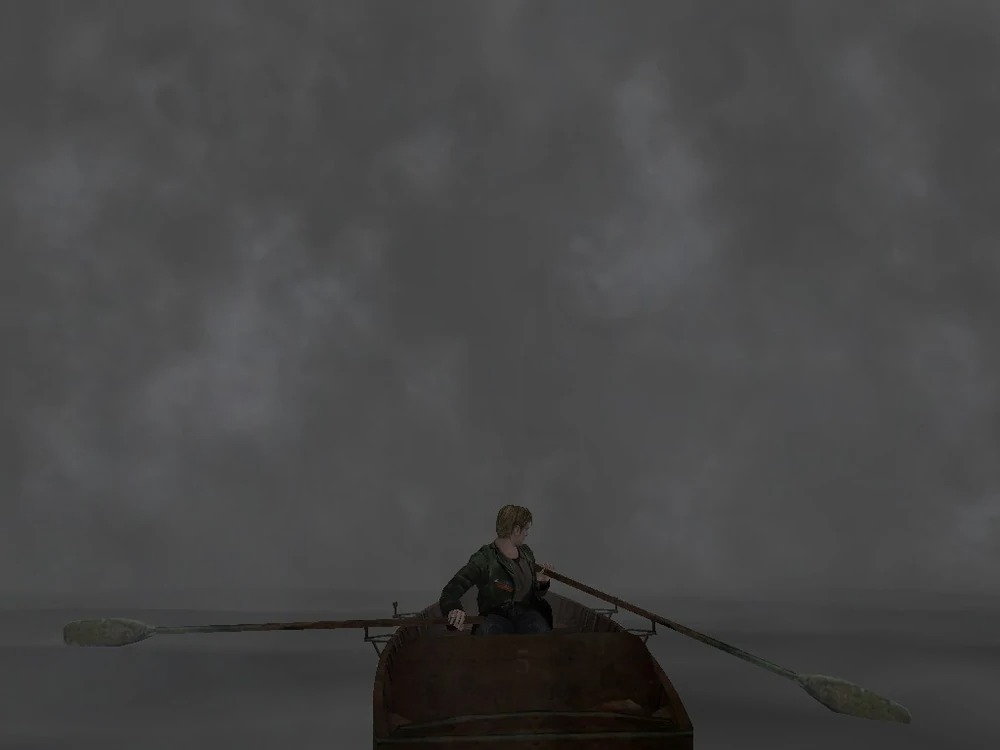

The experience of playing through the final act of Silent Hill starts a bit before entering the Hotel’s doors with a slightly too long row boat ride across Toluca Lake. This sequence’s bare nothingness, quiet and repetitive action for several minutes allows a seeping feeling of dread to settle in, especially as you see the hotel silhouetted through the fog, the only piece of land you’ve encountered throughout your trip across a vast, seemingly endless void of calm water and gray. Through the front entrance of Lakeview Hotel, both James and the player are greeted with expansive darkness and an atonal and distant soundscape. Any of the features that make the Hotel unnerving and cognitively dissonant (like sound effects including footsteps and doors being mixed very loudly compared to the background audio, characters not really talking or affecting like people, animations and their resulting sound not quite lining up) are present throughout the rest of the game, but here they’re slightly adjusted for greater impact.

Much of the first section is silent, amplifying James’ isolation as his rhythmic gait reverberates through the empty space. The quiet also makes encounters much more experientially vicious, as they acutely breach the stillness felt elsewhere. I cannot emphasize enough how every monster encounter (in the Hotel and otherwise) feels wretched and violent. Each monster except for one is a symbol of an aspect of James that he’d rather forget. Much like James they often feel pitiful and tortured as opposed to threatening. They operate much like the Jungian shadow leaking out, a repository for everything James does not want to acknowledge about himself and his deeds. They scream horribly (whether they have a mouth or not) when James blows them apart with shotgun blasts, each having distressed human voices mixed into their formless growls and static. When they’re downed, they wriggle on the ground waiting to be crushed and ended by James, in an act of symbolic self-destruction.

At this early point in the level, the audioscape highlights areas of importance. The consuming and ominous placidity is semi-frequently disrupted by an industrial thrum accompanied by a heavy but nonhuman exhalation. It’s not clear how much of the background audio in the game is diegetic (we know the static that heralds an imminent encounter is), but I interpret almost all of the audio backdrop that isn’t associated with encounters to be the sounds of the hotel’s innards breathing and creaking in acknowledgement of the man it’s waiting to digest. This “music” often accompanies areas where there’s some artifact that echoes a bit of James’ psyche and repression.

Upon exiting a room where a short scene plays out with Laura, the game’s representation of untarnished innocence, James is met with two Abstract Daddies blocking his way through a tight hallway. This is the first time the state of the Hotel changes outside of James’ action. The Abstract Daddy is a very interesting monster to drop on James at this point, as they are the only creature in the game that does not directly arise from James’ experience. Rather, they’re representations of another character’s trauma, a trauma so great that it reverberates outside of her and becomes tangible to others. Functionally, they’re a very apt fit for this section, as their bulk makes them almost impossible to run from, given the constraints of the corridor they’re placed in. Narratively however the metaphor is a bit strained. Fighting through this encounter and entering another room branching off of the main corridor, James is again greeted by that familiar industrial murmur in a room where he discovers a note left by a concierge telling him that he left a video tape in room 312 – the room where he and Mary stayed.

Upon entering, the camera is trained on James at a high angle and from the front. Fixed cameras have been integral to Silent Hill since the beginning. As opposed to some of its earlier contemporaries like the first Resident Evil, which used fixed cameras out of technical necessity, Silent Hill has used them almost purely for aesthetic effect. A fixed camera allows level designers to impart added meaning to scenes based on what they frame, as well as to occlude or draw attention to elements within the frame. The kind of high angle shot is fairly common in Silent Hill 2, but in this space, it is amplified by the camera tracking James as he makes his way towards the concierge desk, adding the omniscient feeling of the hotel watching him. James, and by extension the player, are not agents in and of themselves, but are being watched and guided by something oppressive outside of their control, underscored by the sound of churning remote machinery.

The game shifts tone when James tries to access the Hotel elevator. Downward movement is crucial in Silent Hill games, materializing the descent into a psychological hellscape. The elevator in question won’t move without James becoming lighter. To this end, there is a nearby shelf where the player must deposit every piece of inventory that they have, operationalizing that the items in their inventory do in fact have weight. The elevator groans as it descends, rebelling the entire way. The doors open on the first floor showing a dark L-shaped hallway. At this point, James is entirely defenseless, as well as not having his flashlight or his radio, which emits static and broken moans when monsters are near. Without them, the timbre of the level changes and instantly becomes more oppressive.

This floor uses the classic level design trick of placing a bright red light above a door in order to draw the player towards their next destination. The hotel is guiding James. It wants him to solve its puzzles, leading him deeper into its bowels. Opening a door to a hallway after collecting a key from the red lit room hammers home the aesthetic effect of losing your radio. There’s a single mannequin, an enemy that’s haunted James throughout the entire game obstructing the path ahead. Silent Hill 2’s mannequins are often emblematic of James’ sexual frustration and desires, as they’re two sets of constructed women’s legs roughly sewn together at the waist. Here, however, it’s purely functional. As enemies they do not move until the player gets close; in this corridor, the player has a beat to realize that they do not have the familiar static signaling that a monster’s nearby. Everything feels muted on this floor, the color and audio less pronounced than it is everywhere else, again making material your downward trajectory into a hell of your own making.

———

Hyacinth Nil makes terrible little rooms and synth music that sounds like something in the dark baring its teeth. They like to talk about horror. Follow them on Twitter @Synodai.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 156.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!