So Why Even Do It At All?

This is likely to be one of the most self-indulgent things I’ve written so if self-indulgence bothers you, and I understand, because it bothers me as well, except on some occasions, then by all means get out now. It’s only going to get more unapologetic from here.

I’m three editions into this column and they’ve all been roundly negative about videogames and gaming culture, so much as your feelings about anything can be binarily divided into either negative or positive. Speaking more broadly, since I started writing about games professionally in 2012, I would say the overwhelming majority of my work has, likewise, belonged more to Camp Negative than Camp Positive. I see, in most instances, the worst in games. I never give them the benefit of the doubt. The entire culture of games, for me, is guilty until proven innocent, and consistently fails to engender any kind of optimism or goodwill from me. But writing about games is what I learned to do at school and at university, and I’m not good at anything else, and I don’t want to do anything else, and I count myself seriously lucky that this is how I earn my living.

The computer programmer Darius Kazemi wrote an interactive article in 2013, which was about the time I started writing about games seriously, called “Fuck Videogames”, and I remember the critic Jed Pressgrove calling it “defeatist”, and that’s always stuck with me. I don’t want to feel like that, “fuck videogames”. It’s not that my personality or identity are connected in any way to games’ success or failure as a culture – at least, I don’t think so. But I feel like there has to be more to it than, again, negative or positive, or fuck or don’t fuck. At one time, it was the hope, and feeling like you were on the crest of the wave of something. This is back in like 2013, 2014, when “indie games” were coming to save everything, and mainstream games like The Last of Us and Bioshock Infinite had such powerful press behind them it was unimaginable that single-player games with meaning – or at least attempts at meaning – would ever lose to the multiplayer service-style games that do nothing and go nowhere by design. And then I suppose it was the backlash from all of that, my own personal angry period where it seemed like gaming got so self-satisfied and blithely idealistic, everyone talking about games being “different” now and how they make more money than films and music combined and do this for mental health and that for education, a kind of soft propaganda which for me personally crescendoed/bottomed out at E3 2017 when two multi-millionaires, Yves Guillemot and Shigeru Miyamoto, lept on stage with big toy guns to promote a Mario x Rabbids crossover to much applause and spots in best E3 moments articles. It was trying to say something about this, do something about this, that was why you did it at all.

But looking back on that now, I hate the kind of valiance of it, the crusader sense of putting rights to wrongs and always telling everyone what a lie it is they’re living. I mean, what garbage is that. I don’t really believe any more that criticism of the kind I write has the power to change anything in gaming culture, or really that that matters. This isn’t something that plagues me – I like my work and I don’t spend any time, really, thinking about why I do it or why it’s worthwhile. But I think it’s important for me to make clear that this is not all about just negativity, that although you might write a lot about why games feel inadequate or of a generally low cultural value, there is still something in it for you. The simplest way for me to get there, about what this is, is to frame the rest of this article as a kind of question-and-answer, back-and-forth, letter series type of thing. I don’t like this kind of gimmicks of format, and again I’ll sound for you the self-indulgence alarm. And this is not something I worry about regularly. I have a job where I get to earn a salary working from home writing about videogames. I am okay; I am fortunate. But I don’t think I’ve ever really answered the question for myself, that if all you do is write about what’s wrong with games, why even do it at all? Something is in it for you, alongside the aforementioned, relative vocational comfort, but what? Formal gimmick begins now.

Is this because I love games?

I love some games that I think are very good. I do not love games as a concept. I do not care if games as a form or culture thrive, die, or whatever it may be.

Is it because I want to change games?

It was. But that’s not it any more. I don’t think I have any power whatsoever to change games. I also don’t think it’s my role. I also don’t care any more if they do change. And I don’t know precisely what “change” would even look like.

Is it because I think games, good, bad, or otherwise, are relevant?

This is getting closer. I think they are relevant insofar as they impact our lives and how we feel about ourselves and that they do this perhaps beyond what is commonly considered or perceived. I think one of the reasons I am still interested in games is because I am fascinated in how they affect me – make me insular, selfish, disaffected, and so on, like I have written about in previous editions of this column.

So playing games is a kind of masochism?

No, because I enjoy them, too. I still take a tremendous amount of pleasure from playing, talking about and generally being a participant in games.

But I see their influence as largely negative.

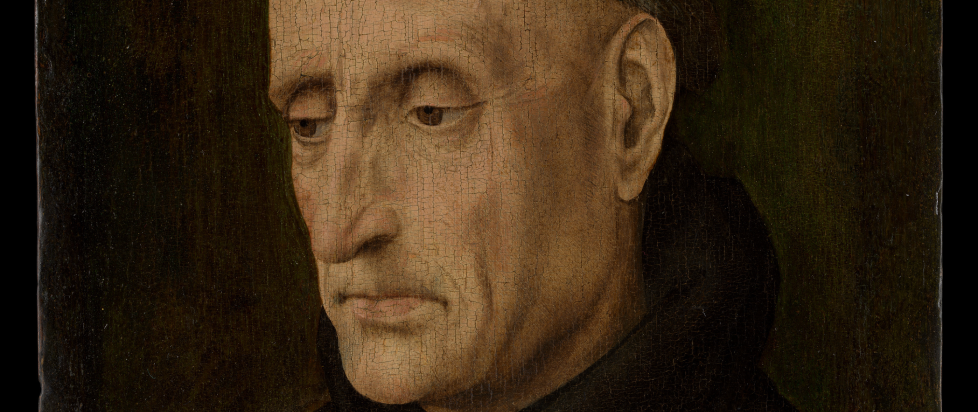

But I suppose I see something valuable in negative experience or influence. What might damage, say, the soul might stir the intellect – to make myself sound like a Benedictine monk. And I take pleasure or at least a kind of gratification or fulfillment from my intellect being as it were stirred.

So this isn’t about defending games.

No.

Or changing them or somehow obliterating the culture of games.

No.

This is like just being along for the ride.

Yes, I think so. But I also feel like that’s a cop out, like it would be better if I had some kind of ideology or goal, which sometimes I feel like I do, which is why I say, for example, I take games as guilty until proven innocent, but that is more like a bias or hangover from feeling burned so many times before, than an encompassing ideal. I am suspicious of games at the same time as enjoying them and relying on them. I also do not have any plan for games that I would like to see fulfilled, like there isn’t some place that I would like them to get to, up or down or otherwise.

So, to tie it off, why even do it all?

It’s not for the love of the games or the hatred of the games. It’s for a love of the depth and broadness and substance of the issues that games present. You can tell from this article that I am spectacularly self-obsessed and kind of mentally or emotionally like onanistic and I think that’s what keeps me interested in games because they provide a pretty constant stream of things to think about and worry about and get obsessed about. I think, more than anything else, games catalyze in me this kind of obsessional inspection and introspection and those are the things that I am in love with, being a product of long-term isolation and therapy and all of those types of things. I guess to be flippant games don’t often provide much to look at, outwardly – they are pretty superficial. And so that invites you to look inward. I guess when looking at games I feel like I am looking at my own reflection, and that I am essentially obsessed with myself.

Edward Smith is a writer from the UK who co-edits Bullet Points Monthly.