Paradise Killer is On a Heavenly Trip

For the devil will drag you under

By the sharp lapel of your checkered coat

Sit down, sit down, sit down, sit down

Sit down, you’re rocking the boat– Frank Loesser

This is the fifth and final installment in my kickoff Paradise Killer series. So far, we’ve explored the game’s design and genre, use of space, nonlinear open world, and passage of time. There’s something really beautiful and special about examining something you love up close, like it’s the bowl of fruit in the center of the art class. I’ve been lucky to sit in different seats and study the light, the shine, the colors, and what’s hidden from some points of view but not others. Oli Clarke Smith’s thoughtful answers to all my questions gave me an embarrassment of riches as I picked what to examine next.

But the column started with something simpler: I’m haunted by Paradise Killer. And in Paradise Killer, the hauntings are all around you. It’s time to spray our blood in service of the lore. (This column contains spoilers for Paradise Killer.)

What does it mean to be haunted? In Strange Pact’s wonderful You Are Haunted jam last year, they put it this way: “Have you ever been visited by the memory of someone you once knew but can’t remember anything about? Have you found the exact same room in every house you’ve lived in? Do you sometimes hear the twisting static of a nighttime radio broadcast whisper your name? If you answered ‘yes’ to any of these questions, then you might be haunted.”

Haunt means to live in or inhabit. Ghosts do haunt, but it’s not the mutually inclusive relationship we may think of. Someone who looks haunted is just as likely preoccupied – the most prosaic ghost is the one that’s only a different part of yourself. Many of the characters in Paradise Killer are haunted by millennia of life, by the nature of life and death on the island, by their mistakes and transgressions. You’re never too old to feel bad about it, I guess.

But the island’s lore offers up a different kind of haunting that’s nestled in a tantalizing Venn diagram of science, religion, and the esoteric. The setting and the story make your head spin a bit, and I think that’s by clever design on the part of Kaizen Game Works. Because its founders both came from AAA game development, they were extremely aware of what they could and couldn’t do with such a tiny team. In game design, it seems like knowing what you can’t do is almost more important than knowing what you can.

“What we never wanted to do was just have collectibles that make a number go up. It was always collectibles that feed into the lore of the world, [because] there’s no combat in the game,” creative director and cofounder Oli Clarke Smith says. “The whiskey drinkers were supposed to trigger at certain story points, but that’s difficult when the story is completely nonlinear and we have no idea what you’ve engaged with. They became more flavor pieces. What we never wanted was the player [seeing the] game monitoring their story progression. That takes away some of their agency by making the player think there is a correct answer to get.”

The nonlinear story is key to the game, and the wild lore serves something else that’s even simpler: Kaizen wanted to make a detective game, but didn’t want to contend with everyone’s well worn mental patterns from decades of following investigations on TV shows. “People would want to do things they’ve seen or heard about but we needed to control that,” Clarke Smith says.

“We started abstracting it into a fantasy world,” he says. “I always loved HP Lovecraft – and the obvious disclaimer is he’s a terrible human being, but at the time when I enjoyed that stuff I didn’t realize the extent and how awful he was. But those ideas of the elder gods really lodged in my head. That’s a really good thing to draw on: that milieu of forgotten parts of Earth’s history and elder demon gods that are actually aliens.”

Lovecraft’s ideas came from his grim xenophobia, but Paradise Killer explores the most cosmic of horrors with joy or, maybe even more interestingly, workmanlike mundanity. This is just life for these people! They live in another dimension and try to leverage their collective spiritual and blood energy to attract gods who are aliens from across the universe. “You syndicate fucks drag us ‘citizens’ from the real world on to your shithole island and treat us like cattle,” human and patsy Henry Division tells Love Dies. “We worship your gods while you leech our psychic energy.”

Late in the game, you begin to realize that the character Witness to the End has been building his own conspiracy to snap the island’s residents into line with his vision of religious zealotry. He explains that the Syndicate built a bunch of huge pyramids but have only ever gotten one god to live with them, Crying Grudge. Crying Grudge has a human-ish body with a skeleton head surrounded by a glass jar. And yes, they are crying.

“Nearly killed by the Persian army at the Battle of Beyond Revenge,” Grudge’s plaque reads. “Body was paraded across the country and displayed above the place in Shushatra Zero. The tears of the god fertilised the ground and the city became a sea of lilies. Syndicate members stole the god back and burned the city to the ground. The god has been moved from island to island ever since.” (You have to ride a jetski to see them: the most vaporwave pilgrimage of all.)

The other gods include “unending skeleton,” “astral engineer,” “many armed iguana,” “harems of fanged men,” “crown of asteroids,” “expert terraformer,” “floating goat head,” and so, so much more. You can see the merging of outer space, science, and earthly spiritual imagery in these descriptions, which serve as flavor in the game. “Space has a stench. It’s full of cosmic horror and existential nightmares,” the demon Shinji tells Love Dies. “I came to this island through a psychic corridor in space. I got a feel for these things.”

Shinji hints at the other-dimensional nature of what the island calls demons. He can’t really hold anything other than small objects and has no physicality of his own. He’s open about the fact that he will perish with the island – one of the heartbreaks I take most personally in the game. Henry is animated from within, or possessed, or haunted, by another demon that he revived from a book. Is this demon like Shinji, something that couldn’t truly live in its own form at all on the island? Are these demons just aliens whose bodies are used to other specific gravities? Are they dark matter, interspersed on a lattice of existence totally perpendicular to ours?

The story culminates in a tale as old as time: power and the illusion of purity. Carmelina has riddled the island with hidden passages and cult-washed her own child into a mindless assassin in order to induce a regime change. Every island, she argues, has eventually fallen to corruption by demons. “Their plan is to charge the particles in our air, stopping demons from being able to latch onto the physicality of the island. The very concrete will repel the demons,” the ghost One Last Kiss explains to Love Dies.

Instead, demons will bounce around “Perfect 25” and land in whatever soft targets they can find: an entire kidnapped workforce of Citizens that will all end up like Henry, with scorched outsides and dead insides held together by other-dimensional forces. Even after an eternity, the corrupt members of the Syndicate still don’t have any better ideas than to torture their stolen underclass for their own enrichment.

In Paradise Killer, the hauntings are all around: Lady Love Dies is haunted by the specter of her own crime against the Syndicate; Carmelina Silence is haunted by how the Syndicate treated her father; Crimson Acid is haunted by the glory she once had on the battlefield; Lydia and Sam are haunted by the idea of a mortal life on Earth. Kaizen has pushed the game’s lore into the furthest reaches of the galaxy in order to tell a story of everyday slights and fears and painfully mundane evils. Love Dies is back for one last case, and she’s definitely too old for this shit.

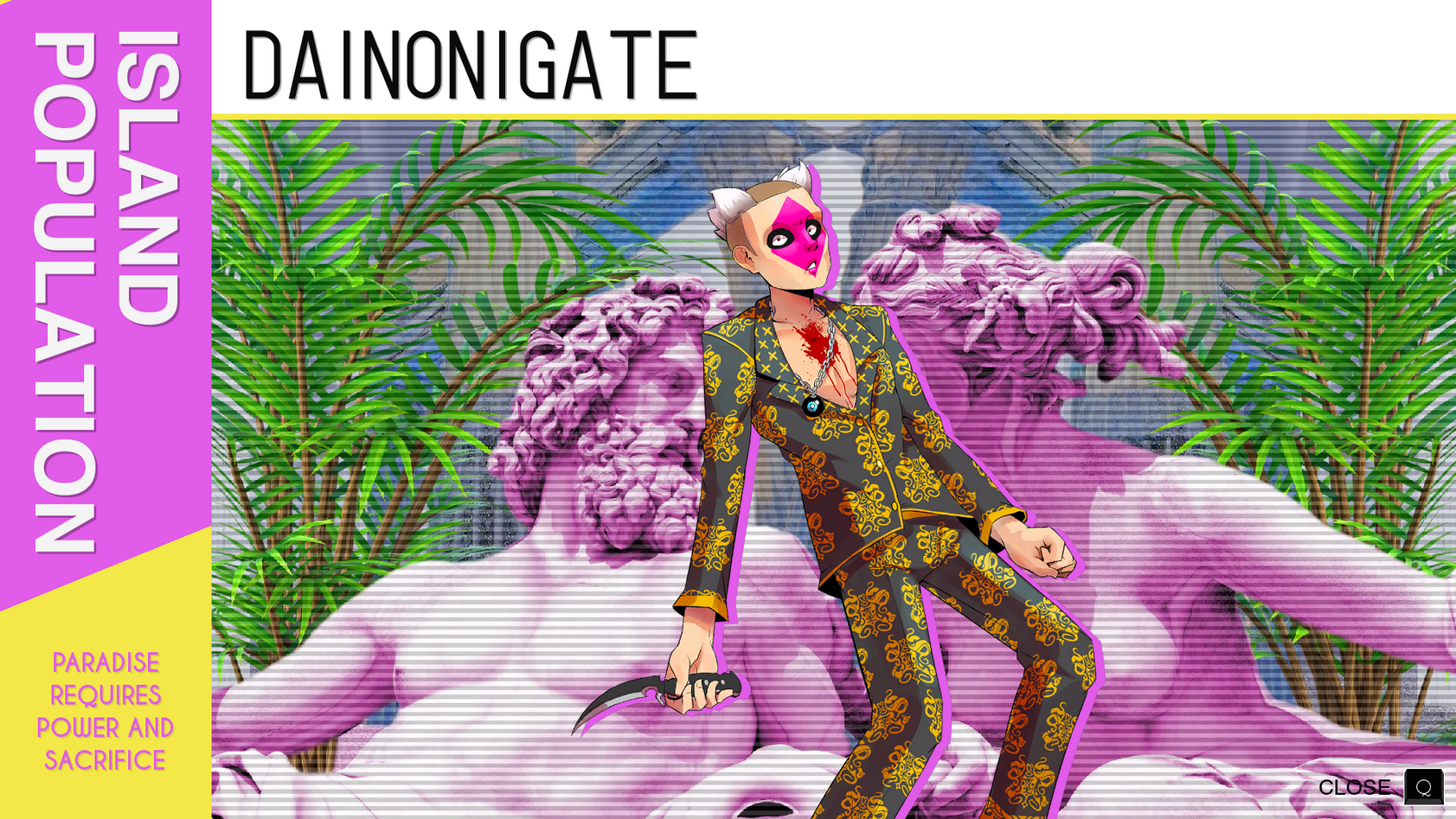

It’s hard to explain exactly why the game struck me so hard and stayed with me this way. There are some straightforward reasons, at least, that I can list. I love adventure games and visual novels and mystery stories. Paradise Killer has bold, outlandish character design that invites you in. The writing is fresh-voiced and strong. There are surprises all over the island, both in expected ways like plot twists and in weird explorations. (Someone told me they started it and got dismayed by Henry’s stomach full of different human bloods. Okay, fair.)

But there’s more than that. It’s… bigger. I don’t know how to explain this, but Paradise Killer both leaves enormous spaces for you to use your imagination and makes it clear that there’s no limit on how beautiful, terrible, human, or inhuman those answers can be. Initial coverage of the game focused a lot on how confident it is: something that might sound expected based on the bona fides of its creators, but is more surprising the more you understand the game. Yes, Kaizen’s confidence shows in how the game turned out; but it took just as much confidence to edit their wild ideas into the right combination.

I played Paradise Killer in 2020 and loved it, but it wasn’t until the following year that I felt how deeply its hooks were in me. That was a really difficult, terrible year for me – something I’m still figuring out how to deal with as I try to move forward. And at an especially dark time, I looked out the window in the city where I live and found myself staring at a nearby rooftop covered in smaller structures and ladders. “This is just Paradise Killer,” I thought. Climb that ladder. Open that door. Jump to another building. And in that moment, something finally shone out of my brain – an idea, a lens, that became an essay on the game’s violent, relentless pursuit of “perfection.”

Kaizen has recently announced that they have a new project. To be honest, I’m curious if they’ll be able to capture lightning in a bottle again; I wouldn’t be surprised or even that upset to learn that Paradise Killer is too much of a combustion of circumstances to be matched even by the same team. But I mentioned Sam Barlow’s game Immortality in a previous column: another AAA developer who escaped into esoteric mystery games and has only continued to find his stride. Indeed, it’s a great time to let yourself sink into a confident, beautiful world filled with mysteries.

For the people all said beware

You’re on a heavenly trip– Frank Loesser

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and enthusiast of just about everything. Her favorite topics include islands, narratives, cosmology, everyday math, and the philosophy of it all.