Tracking a Mechanical Shark

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #154. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #154. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Thoughts about being something else.

———

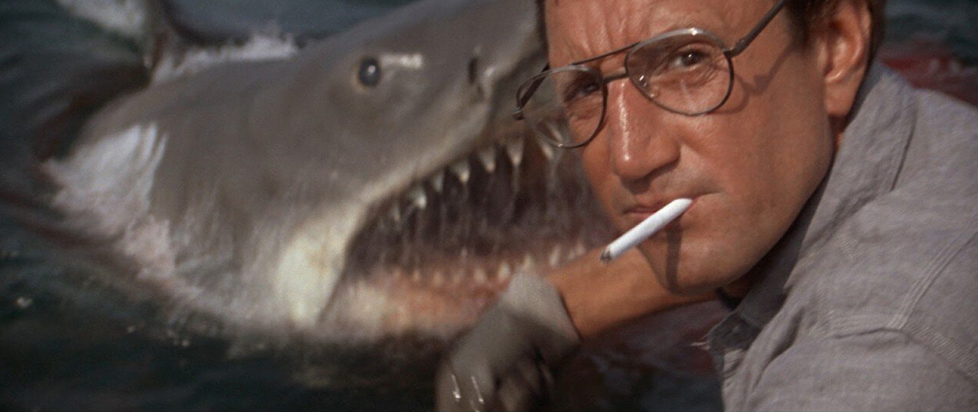

The shark in Jaws is tied to a lot of bad things.

It’s the terrifying villain of a blockbuster movie, so you’d think that would naturally come with the territory. But in a way, it’s gotten out of hand as his negative connotations extend past the big screen and beyond the creative pursuit of horrifying audiences. The movie antagonist echoes the historical shark attacks in New Jersey and with the USS Indianapolis. His film is often held up as a factor in the poor reputation of sharks, making them more of a literal target for human hunters. Now he has some association with COVID-19 given the observations and memes made about the mayor wanting to open the beaches and risk people’s safety for the sake of profit, something that felt disturbingly echoed when the ongoing pandemic first started.

It’s a bit much for what is ultimately a mechanical shark nicknamed Bruce.

Or three mechanical sharks, as the creative team assembled a trio to make the film. While Bruce has had his share of real-world negativity in unexpected (Jaws could not have anticipated an argument to open beaches during a lethal pandemic) and expected ways (the movie clearly meant to take inspiration from the Indianapolis disaster for obvious reasons), he’s also had his positives too in terms of areas like storytelling and art, not to mention inspiring a new generation of shark scientists and conservationists.

The special effects and craft behind the mechanical sharks of Jaws is fascinating. As mentioned before, three were made, each meant for different filming angles—very literally so, since some looked half-built with mechanical guts exposed. So Bruce has interesting animatronics going for him too as another highlight, echoes of old automata like eighteenth-century mechanical swans and tea-serving puppets.

The construction of something like buildings and automobiles honestly doesn’t engage me much. But seeing people try to recreate real or craft imagined creatures with metal and more, and the crossover with automata in some shape – that captures my imagination.

Even when it doesn’t quite work out, as happened with the Bruce trio in Jaws. Each of the mechanical sharks malfunctioned in some way. Saltwater messed with the motors. There was nightly maintenance that included scrubbing and repainting. Bruce sank as soon as filming started. But even in their flaws, the mechanical sharks fueled more creativity, and likely the most important showcase of it.

With the constructed sharks not meeting the intended vision, Steven Spielberg worked around that by minimizing Bruce’s appearance, constructing terror over the unknown and in what couldn’t be seen as he had learned from watching the films of Alfred Hitchcock. Spielberg built up to the shark finally showing up, making direct sight of him a dramatic culmination after withholding his appearance and previously giving hints of it. He even included in-universe indicators of Bruce being present without actually showing him by having shark hunter Quint attach barrels to him via embedded harpoons. John Williams’s signature theme for the shark in Jaws would declare his presence loud and clear. The iconic piece of music even subverted itself, luring the audience into a false sense of security and predictability – just when viewers are trained to expect the shark is nearby once the music kicks in, it’s dead silence when Bruce bursts out of the water while Chief Brody’s back is turned. No melodic warning this time.

Yet during production, Bruce was maligned enough that all three versions of him were just thrown away – something that proved to be an incredibly impulsive and poor judgment call when Jaws turned out to be a colossal hit. Obviously, people would want to see the aquatic star up close in some shape or form. In a stroke of some luck, the mold used to create Bruce still remained (maybe it had been overlooked during the great mechanical shark cull). It enabled the creation of one more shark to hang as decoration at Universal Studios, a photo op for tourists.

One of those tourists would one day revive that shark.

Because Bruce would not be abandoned once, but twice. After another ill-conceived sequel (so ill-conceived that I forgot the sequels existed until I started researching) around 1990, the fourth Bruce would be removed as decoration and exiled to a junkyard in Sun Valley, California.

Except he became decor in the junkyard too.

In a move reminiscent of Dean from The Iron Giant, junkyard owner Sam Adlen kept Bruce, arranging him for display. And instead of hanging him vertically like a fresh kill as had been the case for him at Universal Studios, Adlen horizontally propped him among palm trees. In photos, it looks like an affectionate revisioning of a shark gliding through a tropical forest. The last mechanical shark of Jaws had traded an audience of tourists to a far more private (and arguably more appreciative) audience. Bruce had gone from being strung up like a trophy to prowling impossibly through palm trees.

But eventually more people trickled in, die-hard fans following fellow die-hard fan and NPR reporter Cory Turner as he tracked the surviving Bruce down to Adlen’s junkyard. And then one of those die-hard fans, who’d first seen him as a tourist attraction at Universal Studios and again in a junkyard, would repair Bruce for his debut at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures after Adlen’s son donated him to the then-fledgling institution.

Greg Nicotero, special effects and makeup artist and cofounder of the award-winning KNB EFX Group, restored the shark that played a role in inspiring his career. The Academy Museum didn’t even commission him for the job; he volunteered. Surrounded by reference photos, Nicotero and his team dedicated seven months to repainting and resculpting Bruce. Care, attention, and detail was poured into making this often maligned, overlooked, and abandoned mechanical shark look good as new, to give him more of what he was due. To pay him back for creativity he inspired in the act of building him, in his flaws that pushed a director to new heights, in influencing new artists that had returned to revive him with that same artistic skill they had gained from appreciation of him as a construct formed from human ingenuity.

Even some of Bruce’s original creators visited Nicotero’s workshop and essentially gave the makeover their seal of approval.

Now looking shiny and new, the Academy Museum had to figure out how to install Bruce. Because, fittingly enough, the mechanical great white shark was too big. Pieces of museum glass walls had to be temporarily pulled out to get him inside. And now he hangs there—again, not strung up vertically like a hunted beast as he had been at Universal Studios. Bruce is suspended horizontally like in Adlen’s junkyard, looking more like he’s swimming naturally. Instead of floating among palm trees, he’s now in a pristine white building that could be imagined as an aquarium actually capable of housing a great white shark.

And in retrospect, it makes sense. It’s not like displaying landlocked creatures such as dinosaurs in a museum, mounting them on platforms. Bruce is the animatronic recreation of a shark, and sharks swim in the water. The closest he can get to that is in the sky, the equivalent of gliding through the air, a space reserved only for mechanical sharks imagined and built by human minds.

———

Alyssa Wejebe is a writer and editor specializing in the wide world of arts and entertainment. She has worked in pop culture journalism and in the localization of Japanese light novels. You can find her on Twitter @alyssawejebe.