Paradise Killer’s Biggest Secrets are Straight Up

“In my darkest night,

when the moon was covered

and I roamed through wreckage,

a nimbus-clouded voice

directed me:

‘Live in the layers,

not on the litter.’”–Stanley Kunitz

I am, or I’ve historically been, a retro JRPG player. I’m a Final Fantasy V fan in particular, so I love jokes about Gilgamesh and how the longtime fan translation says the protagonist’s name is Butz. And yes, I recognize myself in every meme about how we all save our elixirs and never use them. But the flipside of those memes is something deeply satisfying about games where you have many tiers of healing items: making exact change to fill your HP.

What does it mean when we say something like that is satisfying? What about the countless YouTube videos of spinning taffy or soap cutting, or Things Fitting Perfectly Into Other Things? Researchers don’t know, and while they have some beginnings of ideas, there’s no consensus. Some believe it might appeal to our feeling of things being finished or being done “just right.” I find it interesting that some satisfying things are additive, like perfectly packing a moving box; while others are subtractive, like watching Robert Redford lathe a tree branch into a baseball bat.

Paradise Killer is an open world game in a vertically stacked environment, giving it a sense of the additive and the subtractive. The world is open, but space is limited; like an apartment building on a high-priced downtown block, the only way to go is up. Even though the island was dreamt into existence from Carmelina Silence’s imagination, it would fit right into the Azores or other chains formed by mountainous undersea ridges. The island also has extraordinary Brutalist architecture that swoops and soars hundreds of feet overhead.

I’ve already gone into detail about the nature of Paradise Killer’s open world as a design philosophy, but it’s this physical stacking of different spaces that led me to pitch this column in the first place. To go from the port at Deep Factory to the Opulent Ziggurat, you don’t only cross the island horizontally; you scale its hypotenuse, culminating in a spiraling climb dotted with obscene statues, blood crystals, and lore. And it’s not just for show. Critical evidence is scattered around the island from very top to bottom.

The island isn’t packed as neatly or squarely as a moving box. It’s piled in some places and spread out in others, leaving negative space as evocative as Javier Bardem’s patchy facial bones in Skyfall. And, pretty quickly, you start to discover weird routes under and around the island’s large obstacles – huge, fascisty architecture like the Dead Zone and the Barracks. All of it is by design, creative director and Kaizen Game Works cofounder Oli Clarke Smith explains.

“That was all to do with density, making sure every bit of the game was dense in traversal options but also dense in interactivity,” Clarke Smith says. “We knew we weren’t going to have pedestrians, we knew we weren’t going to have 3D characters roaming around, we knew we weren’t going to have combat.” Navigating the island becomes another mechanic in the game. When I looked around on Twitter for comments on the small, vague map the game gives you – it’s really more of a heat map for fast travel and save points – I saw a few complain how flat the map is. You might see two locations that appear next to each other, but one is on top of a mountain. As in calculus, the 2D map just doesn’t tell the whole story.

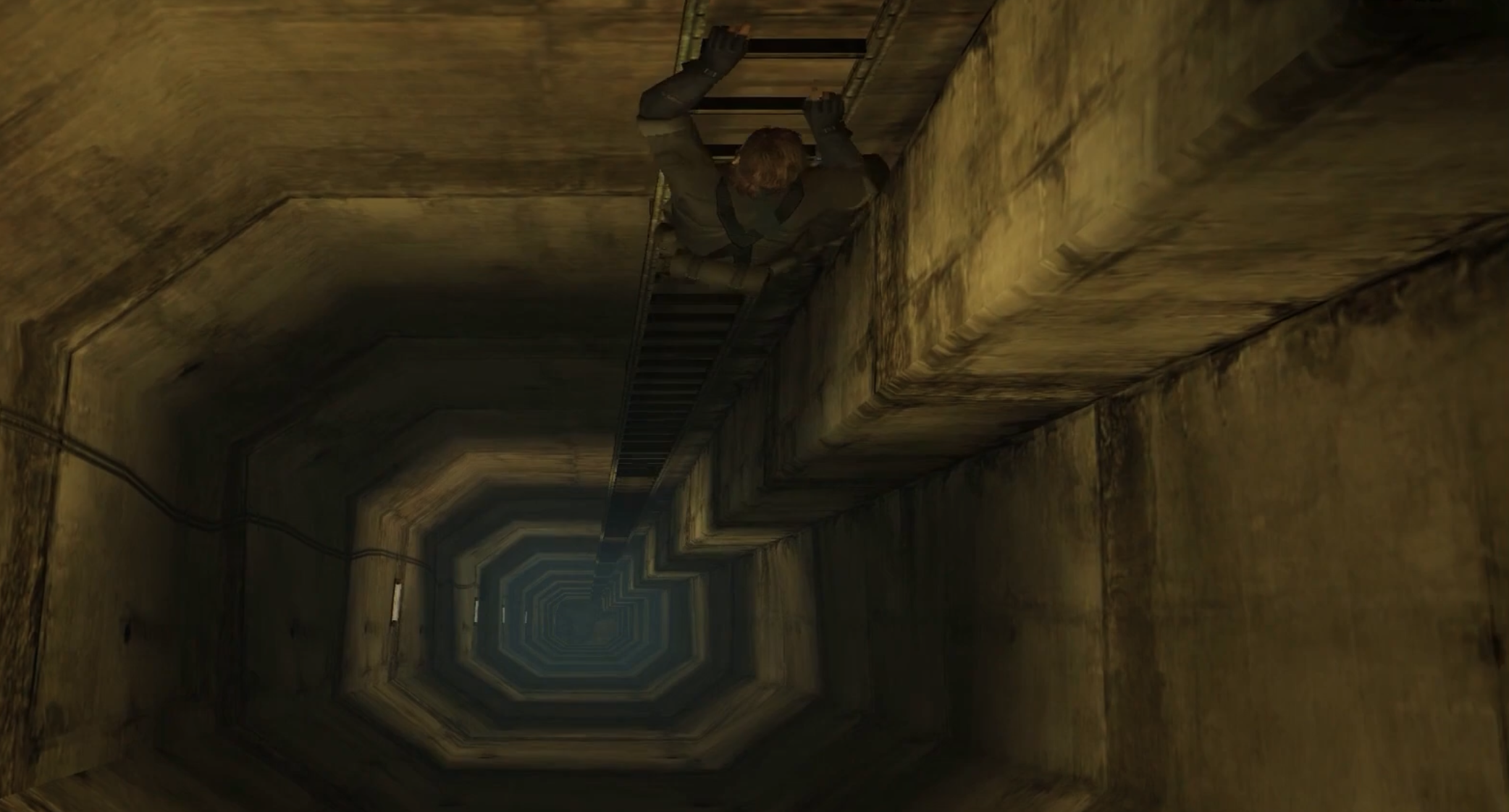

Clarke Smith was inspired by his childhood love of Metal Gear and Resident Evil, but there was only one soulmate when it comes to the island’s stacked and layered design. “Dark Souls was a massive thing for me when I first played that. This world doesn’t care about the player, but it all makes sense and it is all interconnected, and you can access so much of that game should you have the confidence to and the ability to right [away],” Clarke Smith says.

“A lot of open worlds, you look down on them and you see the expanse, right? If you fly the camera all the way up, you see a big expanse,” Clarke Smith says. “Dark Souls is so big, but a lot of it is vertical. You go down to the swamp area, and you can see that looking directly down from a previous area. You don’t realize you’re traversing all of that, but when you make that connection that’s so important – that’s something we really did a lot with Paradise Killer.”

“Dark Souls is just the best level design 3D action game,” Clarke Smith says. “It’s just incredible: that world, those levels, how they interlock, and the intelligence and craftsmanship [are] second to none still. That use of space, the way it twists on you, none of the From [Software] games since Dark Souls have done that. Castlevania games are very good at [it], but I want 3D. Make a game set on an iceberg or something where you can’t go for miles. You just need it all about the interconnected things, or a space station or something. It’s vertical and then intricate.”

This shows in the Paradise Killer map, which has multiple locations you can “cut a cross section,” as Clarke Smith says of Dark Souls. (I own a cross section of my own: artist Scott C.’s painting Lincoln House.) But, thankfully, Kaizen Game Works made the island less puzzling to navigate. “It has different heights, but the interconnectedness, we were way more open with that than Dark Souls,” Clarke Smith says. He enjoyed building paths that hook around from the Beach to Doctor Doom Jazz’s yacht, for example, and the island’s bigger, more secret networks of tunnels, sewers, and… otherwise. (No spoilers!)

My colleague Yussef Cole has written here about Dark Souls several times. He says Clarke Smith’s comments feel true to him, too. “Playing Dark Souls feels like being an ant crawling around a dense rock full of crevices and tunnels. Some tunnels lead you to giant things that will crush you underfoot. Some lead to loot. The process is largely about pushing and prodding at the mass in search of crenellations and soft spots,” Cole says. “You can sometimes see the whole space for what it is: a treacherous honeycomb where no way is truly up and none truly down.”

I’ve previously talked a bit about the game’s beginning, when Lady Love Dies falls back to the island from her exile’s apartment thousands of feet up. It’s clear that the design is meant to be one way, and while you can sometimes glimpse the apartment at the top of its very tall stalk, the game never makes you think you’ll go back there. But that wasn’t always the case. “I put in a stairway and ladder system that takes you back up to the Idle Lands so you’d be able to get back to the starting zone,” Clarke Smith says. “I wanted something at the top that you can’t access when you first start the game, but if you go all the way back up you would find something.”

That plan didn’t last but because of the island’s verticality, stairs, elevators, and ladders do still make up a big chunk of the navigation in Paradise Killer. My friend Glenn Battishill guessed at something Clarke Smith confirmed when we talked: “I was definitely doing that in the style of Metal Gear, where you just climb for ages,” he says. He jokes that he wanted to subvert the style established in Metal Gear by making a very long walk or climb (“from 15 minutes to half an hour”!!!) in order to unlock Fast Travel… and then making the player walk all the way back.

Clarke Smith names two specific locations he loves in the game, and both are, I don’t think coincidentally, very vertical. “I like being on the roof of the apartments, and I like the inside of the council building because it’s got that big tall ceiling,” he says. The apartments are one of the densest areas of the game, packed with lore collectibles and blood crystals and items you need for side quests. The council building is its diametric opposite, with huge empty spaces and maximum vaporwave aesthetics.

Something I’ve only realized since speaking with Clarke Smith several weeks ago is how heterogeneous the world of Paradise Killer is. (For any fellow Adam Ragusea fans out there, I see you.) There are superficial elements that repeat, like the game’s elevators, bright pink ladders, and grotesque statuary. But all the major areas are wildly different. The buildings are in all different styles, or at least all different flavors of Brutalism. The evidence is full of surprises, like the extra body you find or the enormous hands that rise out of the beach.

The island’s chunky, vertical layout is just as varying. You ride an elevator up to the luxury apartments of the immortal Syndicate members but climb twisting stairs to where the mortal Citizens live. In one of the game’s most daunting platforming puzzles, you must take an elevator to the roof and make a precise fall onto a tiny roof below. To access the Dead Zone, you drop into a claustrophobic, trapezoidal tunnel that belongs in the Great Pyramid of Giza. In another puzzle, your reward falls from above in a massive statue’s outstretched hand.

In Ted Chiang’s iconic 1990 story Tower of Babylon, a character climbs seemingly endless stairs into the sky. In Jon Krakauer’s 1996 book Into Thin Air, Krakauer nearly dies in the thin, caustic air at the world’s zenith. Skyscrapers must be able to sway in a strong wind and withstand dozens of lightning strikes each year. It’s frightening, elemental, and even spiritual at the very top. And in Paradise Killer, some of the island’s most revealing clues can only be found by taking a step off its highest ledges.

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and enthusiast of just about everything. Her favorite topics include islands, narratives, cosmology, everyday math, and the philosophy of it all.