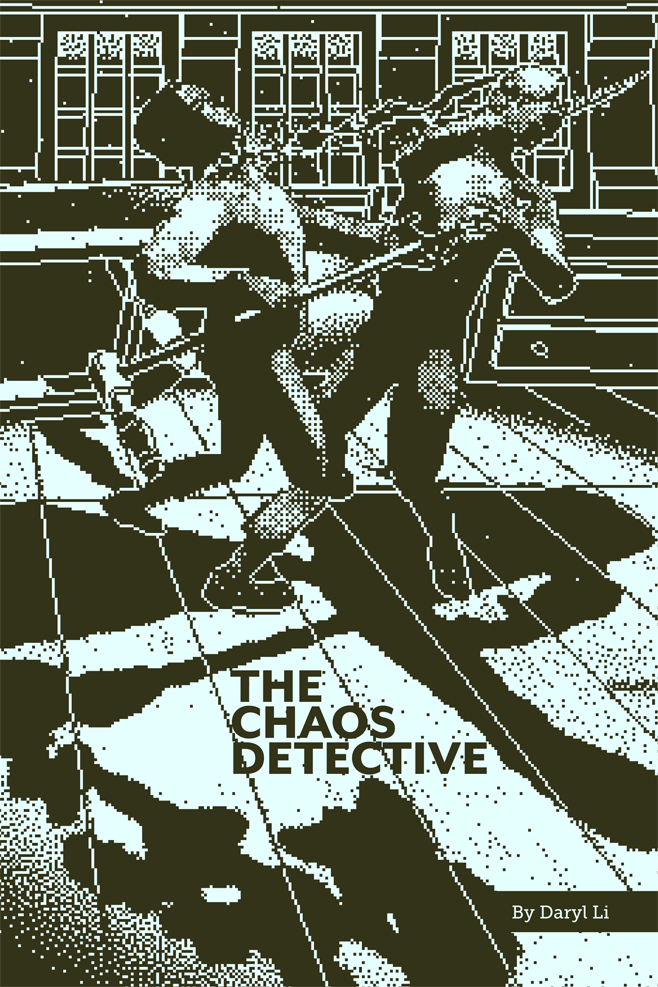

The Chaos Detective

This is an excerpt from the cover story of Unwinnable Monthly #154. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Having read one too many Agatha Christie novels, I became enthralled by the possibilities of detective fiction and murder mysteries at a young age. I quickly came to appreciate that part of the thrill of detective fiction is participatory. The reader tries to piece together the solution as though solving a puzzle.

With the active nature of gameplay and possibility of exploration, videogames seem uniquely predisposed to fulfilling the detective fantasy. Frustratingly, however, solving mysteries in videogames can feel like a dull procedure, transparent puzzles with overly prescribed solutions, a fitting together of pieces structured according to the conventions of game design. Games such as Danganronpa or Phoenix Wright exemplify this, where detective work is generally a matter of picking the right answers or using the right items at the right times, reducing gameplay to little more than point-and-click adventures with thematic dressing.

This is not unusual. Conventionally, videogame design demands a certain degree of predictability and reproducibility – a mechanical fidelity that ensures that the game works as intended. Lucas Pope’s 2018 game The Return of the Obra Dinn, however, addresses these conventions and expectations self-reflexively, creating a taut mystery and game that nonetheless contains elements of uncertainty and the space for interpretation. In doing so, the game supports the detective fantasy by casting the player into the role of textual interpreter, who seeks to organize the chaos into coherent solution.

In Obra Dinn, the titular trade ship reappears along the coast of England five years after her departure from Falmouth in 1802 and subsequent disappearance, with her entire crew presumed missing or dead. As an insurance inspector tasked with uncovering the truth of the Obra Dinn, players work to identify each of the 60 people listed on the ship manifest and to discern their fates using a logbook that provides essential information, tracks game progress, and offers the means to input one’s solutions. Additionally, players have access to a magical watch called the Memento Mortem, allowing them to momentarily jump into snapshots of the past. Revisiting these moments in time, the player walks through what are essentially dioramas, typically centered around moments of death. With these two tools in hand, players proceed to explore the space of the Obra Dinn, locating one corpse after another and using the Memento Mortem to revisit moments in the past. Using the logbook, faces can be matched to names and fates—often the cause of death—from a list of possibilities, much like a game of Clue.

The 60 sets of solutions form the main contents of the game, but the actual mystery of the Obra Dinn is its story, a series of tumultuous events fraught with tragedy, betrayals and sea monsters. The logbook measures the player’s progress while delineating this mystery, ultimately demarcating the game’s boundaries and shape. This is consistent with the demands of a game and the detective genre. A game without well-defined rules and boundaries would likely leave players lost and frustrated.

The game’s structure parallels its fictive archetypes. The unspoken basis of detective fiction is that it presupposes a kind of totality, a closed fiction. All the pieces are there. Every satisfying mystery and game must be solvable, and to that end, everything within this fiction is intentional, has a meaning or purpose, even if that meaning or purpose is to be a red herring.

Yet, The Return of the Obra Dinn also indulges a degree of uncertainty and chaos. While the basic mechanics speak to the imperatives of causality and solvability, the game and indeed overall mystery are characterized by a type of disruptive uncertainty. Obra Dinn avoids the standard mystery solving tropes in game design. In the moment-to-moment gameplay the player quickly discovers that clues are not consumable items with predefined places in which they are utilized. Deductions instead require a synthesizes of contextual clues across a variety of sources, from the snippets of dialogue to their location, from their relationship to other characters to their clothes.

The complexity of investigation in Obra Dinn is further increased by a constant insistence on the incompleteness of knowledge. Players only have access to particular frozen moments, and with the monochromatic retro graphics, it can occasionally even be hard to see what is going on or the identifying characteristics of the faces, requiring players to crosscheck with other scenes. As a result, comparisons across multiple scenes or using processes of elimination is often required when investigating. The game demands that players make sense of the complexity of this reality in a way that hews closer to an actual act of investigation.

Adding to this uncertainty, Obra Dinn disrupts the definition of its boundaries. The ship’s spaces are filled with surprises and branches, as players go up and down the decks, search rooms, and sometimes even follow trails left by spirits to locate new corpses. The next available corpse might even be hidden in a barrel, with little more than a few buzzing flies to give its location away. Despite the defined limits of the logbook, the shape and size of the puzzle is never clear. It starts simply enough, with the discovery of one body leading to another, but quickly spirals into a complicated web.

Deep into the game, more characters are introduced to the player and more questions posed at the same time. Threads spin wildly out, with some scenes contain over a dozen characters. Several pages in the logbook remain half-answered for extended lengths of time. It becomes impossible to keep track of all the clues, characters, and deductions. The same is true about the narrative, which weaves its way through surprises and twists in a seemingly ever-expanding story. Diving into The Return of the Obra Dinn, one constantly peels away, with no sense of just how deep the rabbit hole goes.

———

Daryl Li is a writer of fiction and nonfiction based in Singapore. His work generally explores themes of memory, identity and trauma. He also enjoys writing about games, music and film. The Inventors, a full-length collection of his literary nonfiction, is forthcoming from TrendLit Publishing in 2023. Follow him on Twitter @nonstickpanda.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 154.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!