Anything

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #152. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

Recently I’ve been listening to a lot of the White Pube, the games and art site/podcast run by Gabrielle De La Puente and Zarina Muhammad. Every week for several years, they’ve published a critical examination of a text, broadly defined – recent texts include Red Dead Redemption 2, the experience of hunger when fasting and the Instagram account @afffirmations. I like this series because it inevitably pairs the text with one or both hosts’ personal experiences of it. There’s something really appealing about picking something that fascinates you and spending time thinking about how you relate to it, whether that thing is a game or a low-quality jpeg. And I like this brand of criticism, because it seems honest to me about the parts of ourselves as fans of things that we frequently elide.

I’ve been thinking about my critical likes and dislikes recently, as I’ve had the opportunity here in this column and elsewhere to reconsider how I can contribute to critical conversations around games, literature and other media. I returned recently to this interview with Jo Livingstone in which they say “I feel an ethical duty to take every work of art seriously and ignore how famous or prominent the person who made it is.” The duty of care and attention to something likewise strikes me as a fruitful way to think about engaging with art. Still, I can’t shake the question: what does it mean to be a critic?

I’m thinking about this question because I’m thinking about being sixteen. Looking back at yourself as you were in high school is an exercise in honesty. Of course, my first impulse is to present the parts of myself that I remember and like, the parts I hope I’ve kept. For instance, the me that played CDs I burned from the public library in my dad’s car the year I got my driver’s license, playing what I could get from the stacks chosen by Gen X librarians guessing what teenagers would like – at first Franz Ferdinand, the Magnetic Fields, as a joke and then seriously the Barenaked Ladies’ middle three albums, and then for one summer just the New Pornographers’ album Together, on repeat:

You have secrets from them, you have secrets but they’re spent – all that kept the lights on when the power went

There’s that me, who worked at a bookstore and had mostly classic literature on her employee recommendations shelf, and then there’s the one who spent her paycheck on fantasy and YA fiction, who drew fanart, who went home on days she didn’t work and wrote her dystopian novel, while listening to – I’m serious – Bridge Over Troubled Water on her iPod.

I wasn’t open about my interest in games as a teenager. I had a few friends in art class who liked RPGs, and I’d listen to them talk as if I didn’t know what things like mana or experience points were and laugh at all the points in the conversation that would indicate confusion and mild interest. In fact, I was just as conversant in those systems as they were, and my new disposable income made this the first time I could really engage with games on my own terms and consider what I liked about them.

If being a good critic involves being able to assess your relationship to something with honesty, then I was a poor one, because I wanted to disavow the relationship entirely. And this assumes the “you’re a writer if you write” kind of approach to defining oneself as a critic – any criticism or nuanced thought I had about the texts I spent time with was only for me, only private. I wanted games to be art, as the old saw went and still goes, partly because I wanted to be able to like them in the way I liked music or books – to wield them in such a way that people could recognize a depth in me that was otherwise invisible.

The early 2010s were a good time to be considering a new approach to what games could be. 2012 was the year I played Bastion, the game that made me understand how storytelling could be integrated into player action in games in a way no other medium could do. It was also the year I played Portal 2, the most graphically intense game my computer could run, and took many hours more than I needed to complete it because I couldn’t stop zooming in on textures- graffiti on walls, fluorescent lights, broken panels hiding tables and chairs that seemed like they could move, if only they were in reach.

But the truth is that the main way I engaged with the games I was playing wasn’t as art. I also spent my fair share of time playing games that were not good, for no good reason. I played Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning, a very average RPG that cemented my hatred of overdone lore and my need to always try and fail to complete any herb collection a game gives me. I loved the micromanagement of RPGs, and the process of building something up optimally over time, both of which are tendencies that could be expressed artistically, but more than that I liked being a mage who could incinerate a bunch of dudes. Two Dots, which I played mostly on buses and airplanes, is a simple puzzle game with no story that I put dozens of hours into. Its bright circles interspersed with obstacles themed around levels, jungles and science labs and outer space, are admittedly a stone’s throw from minimalistic corporate-ish art. But my critical engagement with the game ends there. I liked it because I could play it in places where I didn’t have an internet connection.

I think a large part of being a good critic is being able to be sincere. And part of that sincerity is admitting that sometimes, you just like what you like. And sometimes what you like isn’t art. Or it’s art to you, but not to someone else: to someone else it’s a clicker game, a bad fourth album, an idea that falls flat when you try to express it.

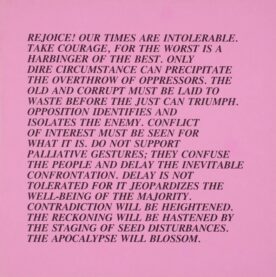

A few months ago at MOMA, I saw Jenny Holzer’s collaboration with Lady Pink, Trust visions that don’t feature buckets of blood. Afterwards I looked up her Truisms series, the most famous of which you’ve likely heard: Abuse of power comes as no surprise. There are hundreds more:

Abstraction is a kind of decadence

The more you know the better off you are

Description is more valuable than metaphor

Confusing yourself is a way to stay honest

The most profound things are inexpressible

But this one is my favorite:

Anything is a legitimate area of investigation

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.