Carnage and Blood: Two Kung Fu Movies from Opposite Ends of the Genre’s Heyday, Both with Numbers in the Titles

There really is precious little to tie these two films together, except that they’re both kung fu movies given fancy Blu-ray releases by Arrow Video around the same time. One helped to kickstart the golden age of kung fu cinema, the other was released near its end. One is made by the acknowledged masters at Shaw Brothers Studio, the other by the rival Golden Harvest. One is a bloody Saturday morning cartoon that barely bothers to connect its interminable fight scenes with any kind of story, the other an elegiac lament about the inadequacy of heroism in the face of death. Both are kung fu movies though – both are bloody and both have numbers in their English-language titles. That’s not nothing.

“If you use your martial arts to hurt others, that becomes the greatest taboo against your training.” – One-Armed Boxer (1972)

Did you ever wish that your kung fu movie could just be nonstop fight scenes, unencumbered by things like dialogue or plot? Look no further! Would you like said fight scenes to also be entertaining at all? Best move along.

Another in a long line of movies in which villains bring in a rogues’ gallery of foreign fighters as ringers, One-Armed Boxer was one of the earliest kung fu movies as we know them today. Created by writer, director, and star “Jimmy” Wang Yu, who had previously been one of Hong Kong’s biggest action draws, One-Armed Boxer was a follow-up to 1970’s The Chinese Boxer, both of which helped to set the template for what kung fu films would become.

Yu had previously been under contract with Shaw Bros. when he defected to Golden Harvest, a rival studio in Taiwan, breaking his contract in an act that could have been a plot point in a kung fu movie itself. The Chinese Boxer and One-Armed Boxer – the latter of which borrowed heavily from an earlier wuxia film he had done with Chang Cheh, One-Armed Swordsman – were among the earliest films he made for Golden Harvest, and he would later reprise his role from One-Armed Boxer in its notorious sequel, Master of the Flying Guillotine.

Unfortunately, “first” doesn’t necessarily mean “best.” I haven’t seen The Chinese Boxer, but compared to what the folks at Shaw Bros. were already doing with the kung fu genre by the time this film hit marquees (it was released the same year as the much better King Boxer), One-Armed Boxer is a cartoon. Worse yet, it’s a boring one.

The plot is as bare-bones as they come, concerning a martial artist whose school is wiped out by the aforementioned foreign ringers and who vows revenge, in spite of the fact that the karate master from Okinawa (who has Dracula fangs, for some reason) karate chopped his arm off. Fortunately, there’s an herbal remedy for getting your arm chopped off, even if it involves burning your remaining arm in a fire while cranking the theme from Shaft.

One-Armed Boxer isn’t concerned with plot, though. Much of it happens via montage, and rarely do more than a couple of minutes pass without a fight breaking out. As we previously saw with films like Five Shaolin Masters, however, too many fight scenes can become tedious, even when they’re emphatically what we’re here to see.

The fact that the fights are too frequent, with too little connective tissue to hold them together, isn’t the real problem here, however. The real problem is that they’re mostly terrible, consisting of little more than guys waving their arms at one another while yelling. Again, compared to what was coming out of some other studios at the same time, the fights seem tired and stilted already, in spite of the wild array of weirdo opponents, including the aforementioned karate vampire, a Tibetan lama who can puff up like a blowfish, and an Indian yogi in unfortunate blackface, to name just a few.

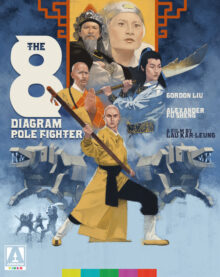

“The other wolves will smell blood and so understand the agony of dying.” – 8 Diagram Pole Fighter (1983)

Often claimed as director Lau Kar-leung’s masterpiece (the back of the Arrow Video Blu-ray is one place that makes such a boast), 8 Diagram Pole Fighter was released toward the end of the Shaw Brothers’ golden age. Within just a few years, the studio’s output would drop from literally dozens of films per year to just one or two.

Further hampered by the tragic death of one of its stars midway through production, it would have been easy enough for 8 Diagram Pole Fighter to fall apart under the strain, but instead it pulled together, as Lau Kar-leung channeled his own grief at his friend and protégé’s untimely death into the revamped script. According to an essay about the film’s troubled production by Terrence Brady, Gordon Liu, the flick’s other star, “stated that his grief was present throughout filming, and in some of the picture’s emotive scenes, his tears were genuine as it provided him an outlet to cry.”

The death of Alexander Fu Sheng, who plays the Sixth Brother in the film, driven mad by grief at the betrayal of his family and the slaughter of his father and all but one of his brothers, certainly changes the tone of the picture. While many of Lau Kar-leung’s films, several of which I wrote about when reviewing the Shawscope boxed set from Arrow, are unique among their peers for various reasons, 8 Diagram Pole Fighter tackles the aftereffects of grief and failure in a way that feels more visceral than most other films of its type.

“Fu Sheng’s passing sullied the film’s landscape,” Brady writes in the booklet, “which became riddled with pessimism, trauma, and rage,” while the back of the box advertises that the movie is “as elegiac and suffused with anguish as it is thrillingly violent.”

The story, rooted in Chinese folk history, concerns a patriotic family of seven sons who are betrayed and slain, with two exceptions. Fu Sheng plays one, whose trauma at the sight of this violence breaks him utterly. Gordon Liu plays the other, who seeks refuge from the world in monastic life, though he is unable to shed enough of his rage to truly embrace Buddha.

In the original script, Fu Sheng’s character was supposed to regain his senses and convince his brother to join him in seeking revenge, but his untimely death in real life means that his character vanishes from the film midway through, never to obtain any kind of closure. Liu’s character, meanwhile, may eventually exact his vengeance, but he never truly finds a place to belong, and both seem more damaged by what they’ve seen than is usual for a character in a picture like this. Chalk it up to real-life trauma bleeding through into the finished product.

There’s some physical trauma, before all is said and done, too. Shortly after calling the film “thrillingly violent,” the back of the box makes reference to the “teeth-smashing climax,” and it ain’t kidding. The monks, it seems, train in a style of pole fighting designed to break the teeth of any wolves that come to harry the monastery, since they don’t believe in killing. And before all is said and done, that tooth-breaking style is put to work on lots of humans in a sequence that is far from the bloodiest that I’ve seen in one of these Shaw Bros. pictures, but may well be the most horrifying.