Good Kung Fu Part Three: Shawscope Volume One from Arrow Video

Perhaps the most surprising thing that develops over the course of watching the dozen movies in this Shawscope boxed set from Arrow Video is how much variety is possible within what are, essentially, a bunch of fairly same-y kung fu pictures (with one exception), often by the same couple of directors and with the same handful of stars. While the pictures contained herein may not lend themselves to binge-watching, they provide a surprising amount of variability, even when watched all in the space of a month, as I did.

“If you’re broke, you’re doomed.” – Chinatown Kid (1977)

The essay on Chinatown Kid in the Shawscope boxed set makes much of director Chang Cheh’s affection for his young star, Alexander Fu Sheng, quoting the director’s memoir where he describes Sheng’s qualities: “good-looking, excellent physique, a delicate blend of rebelliousness and liveliness, a good comic sense.” There’s good reason to spend such time on Sheng, though – and Chang Cheh’s fondness for him. Sheng carries Chinatown Kid, and Cheh’s camera loves him.

On paper, Chinatown Kid reads like what it mostly is: a pretty standard story about a provincial kid who’s good at kung fu, who rises to the top of a criminal syndicate only to be brought low by the disloyalty of the people around him. In fact, its arc shares more than a little in common in The Boxer from Shantung, another Chang Cheh joint from earlier in this collection

The big difference here is that Chinatown Kid is set in then-modern-day San Francisco, at least eventually. In the 115-minute international cut available on the Blu-ray (I haven’t watched the shorter, 90-minute version to compare), it spends a lot of time in Hong Kong, setting up the reasons why Sheng’s character ends up in San Francisco, and why he can’t afford to get caught and deported.

Which means that instead of just the story of a naïve kid from the country caught up in the rat race, it becomes a tale about the immigrant experience – even if most of the film was actually shot on soundstages, and the scenes in America are frequently less-than-convincing, complete with cars boasting steering wheels on the wrong side.

The rest of what that makes Chinatown Kid stand out is simply Sheng himself. His character’s charm carries the picture, and Cheh puts him to use well. The fight scenes are surprisingly few and far between, but they’re solid when they happen, and there’s something so refreshing about Sheng’s youthful but never arrogant confidence, and how it is never punctured.

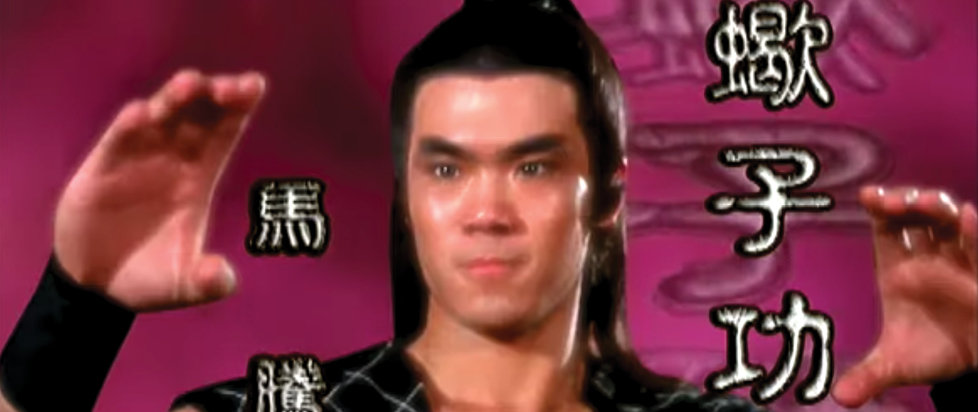

“You will continue to do evil things. Once you start, there’s no end.” – The Five Venoms (1978)

As I mentioned all the way back when we started this adventure, Five Venoms (I actually prefer the Five Deadly Venoms title) was basically my first Shaw Bros. picture and, now that I’m more than halfway through this set, it might still be my favorite. What got picked up on, replicated, borrowed, homage, copied, and even satirized a million times over the years might be the “five kung fu masters with weird powers” angle, but what really makes this movie sing is the unlikely who’s who murder mystery structure. Hell, I’ve even seen the film called “Hitchcockian,” which is almost certainly a stretch, but it’s definitely an absolute joy to watch.

“A broken body can be healed, but not a broken spirit.” – Crippled Avengers (1978)

Essentially a sequel to Five Deadly Venoms, Crippled Avengers reunites pretty much the entire cast (aka the “Venom Mob”) with director Chang Cheh for another total home run of a kung fu picture. As you might imagine from the title, Crippled Avengers is not necessarily the most sensitive film in the catalog, but it boasts some of the most exuberant fight choreography ever put on film – handled by Robert Tai Chi Hsien along with stars Chiang Sheng and Lu Feng. In fact, Crippled Avengers was initially released stateside as Return of the Five Deadly Venoms, even though it… definitely isn’t.

In fact, its inciting incident is more than a little distressing. Within 5 minutes, a gang of warriors have killed a woman by cutting off her legs and also chopped off the arms of a young boy. While one might imagine that this was the beginning of a fairly bog-standard revenge narrative, instead these prove to be the wife and child of our film’s villain.

The boy grows up, and his dad makes him iron arms that extend and fire projectiles, as one does. But both father and son have become twisted by the experience, and they delight in maiming and “crippling” those who cross them. Here’s where our heroes come in. Several guys who don’t know kung fu and just happen to get on the bad side of this warlord and his cyborg kid. One gets deafened, one gets blinded, and one has his legs chopped off. When a young kung fu master comes to their aid, he gets brain damage.

Naturally, his master opts to train the lot of them in kung fu, helping them turn their disabilities into strengths, and the group team up to get their revenge. Despite that rather grim opening, the movie is delightful rather than dark, and features plenty of jokey moments and fight choreography that sometimes feels more like watching circus acrobats than kung fu masters.

“He could use Ninjutsu to attack at any time and take you by surprise.” – Heroes of the East (1978)

Each of Lau Kar-leung’s films in this set feel like a different way of getting at his raison d’etre, which is promoting the “moral discipline” of martial arts. While the booklet that accompanies the Shawscope box makes much of director Chang Cheh’s dissatisfaction with kung fu movies as a whole, quoting him as dismissing them as “tired, worn out wuxia and fist-and-kick action films” that “warrant little mention,” Lau Kar-leung seems endlessly dedicated to the martial arts, and his films are only interested in showcasing them at their best.

In this case, that takes the form of a domestic squabble between a Japanese bride and her new Chinese husband. The two are obviously very much in love, but they’re also proud and stubborn – think of it as Pride and Prejudice, but with a lot more kicking. She wants him to learn Japanese martial arts, he wants her to learn kung fu, and both of them keep escalating the disagreement until they’re sparring in the dining room, destroying furniture, and flustering each other beyond belief.

Eventually, she returns to Japan and he and his comic relief servant cook up a scheme to get her back by challenging her to a duel. Unfortunately, because of their escalating bickering over which nation’s martial arts are better, the letter is worded to sound like a challenge from all Chinese martial arts to all Japanese styles – leading a group of various Japanese masters, all representing different styles, to travel to China in order to challenge our beleaguered protagonist, played by Gordon Liu.

It’s the rare Hong Kong film of the era that paints China’s neighbors in a flattering light, even if Chinese-style martial arts do ultimately come out on top time and again. What’s clearly more important to Lau Kar-leung, however, is the underlying message: that martial arts should not be about petty competition, but cooperation and self-improvement, learning from one another rather than engaging in constant one-upmanship.

The fight scenes may literally tie up the entire back half of the movie, but they are all beautifully choreographed and edited, and do a very nice job of showcasing the differences in the styles. (Also, I could watch Yasuaki Kurata do the “crab fist” style all day.) Unfortunately, the opening domestic comedy sequences drag on longer than they need to, and the film ends too abruptly, largely abandoning Yuka Mizuno’s rambunctious Japanese wife after the first half, despite her being pretty clearly the most charming character in the picture.

“Even a blind man can tell that you are dead.” – Dirty Ho (1979)

Leaving aside the Beavis and Butthead chuckle-inducing title, Dirty Ho is still a weird experience. From its opening titles, which are staged like a musical number, it is more overtly a comedy than perhaps any other film in this set. Every fight scene feels more like a dance sequence or a vaudeville act, and even the plot (which the one sentence Letterboxd synopsis manages to contain spoilers for) feels more like a perfunctory excuse for the various set pieces than anything the film is interested in exploring.

Like pretty much every Lau Kar-leung flick in this set, it ends on a weird freeze-frame, and almost more abruptly so than any of the others, without meaningfully wrapping up pretty much a single plot thread. And yet, none of this makes the movie not kind of a joy to watch, and the dance-like fight scenes are certainly inventive, which is an impressive accomplishment, after so many kung fu movies all in a row.

It’s also the last movie in this extensive (if far from exhaustive) set, though not the last disc, and it feels perhaps apropos that we opened with maybe the most quintessential kung fu movie of the bunch and closed with one of the oddest. After this, though, there are two more discs, both of them CDs loaded with music cues from all over this substantial catalogue of films.

In all, it’s an impressive collection, if one that is probably more than the casual viewer could really ever need, rendered all the more so by the knowledge that a Volume Two is already in production and should be on its way to us very soon…