Better Late than Never

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #145. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Finding deeper meaning beneath the virtual surface.

———

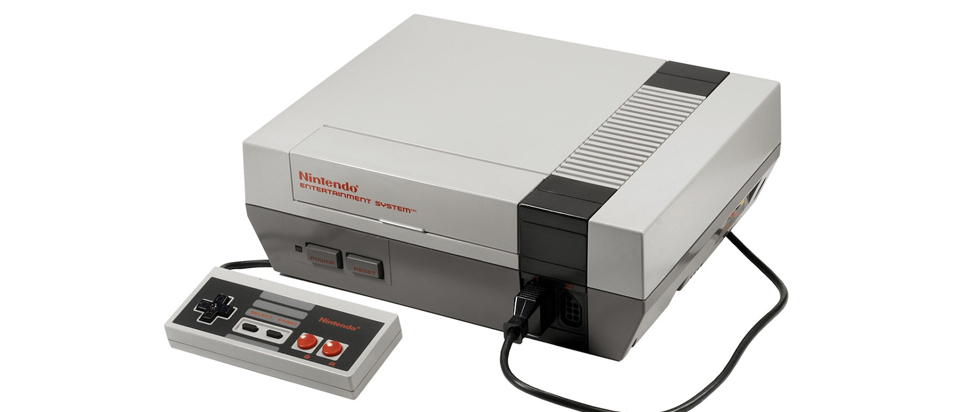

When, on a Christmas morning in the late eighties, my brother and I unwrapped the giant box containing our first gaming console, the Nintendo Entertainment System, it had already been several years since it first splashily premiered in the States. Our friends at school were already long tired of comparing high scores in Duck Hunt, secret areas in Super Mario Bros. or high-score stratagems for Excitebike. Though I desperately yearned to join them, I had been forced to wait, to bide my time; to play in the park (ugh), to read books (blech), to blister our thumbs on the cheap, lo-fi handhelds we found at flea markets and gift shops.

When we did finally receive that pristine grey and black box lined with catchy blurbs and in-game screenshots, and opened it to reveal a smaller, plastic grey and black box that we plugged into our wood-grained TV’s RF connector, we were overjoyed, nonetheless. Finally, my brother and I could gain entrance into the ranks of the deserving, could learn to speak with the same nouns and verbs, could trade cartridges and gameplay tips and get the same Nintendo Power subscription as everyone else. True, we were not the vanguard, not that special class of kids who picked up the console when it first landed on American shores, but we could still gain a narrow access. It was in search of this access that we remained consumed with for the rest of our childhood and well into our teenage years.

Getting consoles years after their social relevance was a pattern that would repeat itself throughout our young lives. When we received a Sega Genesis, it was already several years past its prime. Our copy came with new-fangled six button controllers rather than the original, classic three (a telltale manifestation of mid-cycle superfluous upgrades meant to spur new sales). Later, we got the Sega CD and 32X, hardware add-ons to the Genesis which generated next to no discussion among our uninterested peers. No one wanted to hear about the full motion video fidelity of classics like Sewer Shark, where B-actors shouted commands to the player and quoted Apocalypse Now at us. No one cared about the marginally increased fidelity these upgrades offered, or the better sound quality coming from the early adoption of compact disc-based media.

The 32X was even less well received. I remember leading my exhausted mother through the seemingly endless, maze-like aisles of our local Toys R’ Us, trying to locate a console which might satisfy her strict price limits. We found the 32X sitting alone in an abandoned and cleared-out aisle, its box disheveled and falling apart, the platonic ideal for an undesirable, uninteresting product. But it was what I could acquire, it was an access point; many shades removed from a golden ticket, yet which still allowed me to remain in that sanctified club, even if it didn’t provide me with much material with which to actively participate.

But that’s just the way things were. So much of the drama of attending public school seemed to come down to being exposed to different social groups and different families, with drastically different priorities and coping mechanisms in the face of capitalism and the realities of living and working under it. Part of the reason why my parents declined to provide me with the means to show off some form of petty wealth to my peers was because their priorities lay decidedly elsewhere: they sought physical escape, in the form of travel, and connection with overseas family. And that trumped the dreams my brother and I had for escape by way of glowing screens, and the cachet those screens held to our friends and classmates.

My mother was born in Tunisia and immigrated to the States in her twenties. Her yearning for the family she had left on the other side of the Atlantic was something I was keenly aware of as a child. To rectify this, we would fly to Tunisia nearly every summer and stay with family, sometimes for a month or longer. This was, without a doubt, a luxury for our working-class family. The international flight was tremendously costly and amounted to a great financial strain on my overworked, underpaid parents.

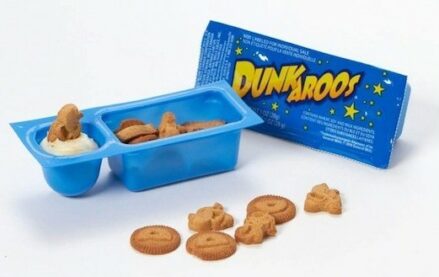

As children, my brother and I couldn’t really comprehend any of this. We could only understand luxury in the small scale, in the toys and clothes in front of us, in the larger-than-life stories we could use to impress our classmates. The recognizable currency of our social capital came from universally accepted sources, like the stuff you’d see advertised in television commercials in between episodes of Saturday morning cartoons. No one we knew could tabulate the impact or benefit of traveling to a distant country full of alien food, foreign languages and souvenirs of incomprehensible shape and application. I was being dealt a bad hand with these trips to Tunisia. I couldn’t sell this, couldn’t use the pistachio sweets we brought back to trade at the cafeteria table for Bubble Yum, Hot Wheel Cars or Dunkaroos. It made me an outsider even as it broadened my understanding of the world, and, in many ways, helped our family soothe over its troubles and pain at home.

In Tunisia, my parents rarely fought. The liminal fantasy space of the vacation and the foreign setting, away from work and the stresses of money, allowed them a peaceful, if temporary reprieve. The distance allowed them to see one another less as providers or as burdens, but as regular people, deserving of kindness, happiness and love.

As for my brother and I, Tunisia allowed us the chance to be normal, well-rounded children. It gave us a chance to break away from the magnetic force of the TV screens back home, the childhood held under sway of relentless materialism and digital fascinations. In Tunisia, we’d run around the neighborhood in bare feet alongside our cousins and their friends. We’d chase each other down alleys, through the older folks’ cooking and conversations, up onto the unfinished second stories of houses, skinning our hands and knees on jagged concrete and exposed rebar. It was both exhilarating and exhausting and we’d fall asleep each night in an instant, waking up early the next morning to do it all again.

The memory of videogames would lay dormant in our imaginations, at least until we returned home. It would take time, going back to school, feeling the odd shapes of our robust suntans and scarred elbows jutting painfully against the smooth American cultural institutions. But eventually, inevitably, the suntans, the scars, the memory of our summers would go away and we’d be back to wondering why we weren’t allowed to buy the latest game, why our old consoles weren’t turning heads or winning us favors, why nobody wanted to come over to try and beat Sewer Shark with us or to challenge me in Eternal Champions. The parts of myself that I gained access to during my trips, I’d lose, again and again to the same worries and concerns.

The rest of my family would struggle in their own ways: mom tearfully chatting the hours away with her sisters over the phone, dad disappearing into his work, brother sick with a cold or earache again, fighting me for the controller and remaining save slots. Familiar shapes which still felt painfully awkward every single time we were forced to put them back on.

———

Yussef Cole is a writer and a visual artist hailing from the Bronx, NY. He makes images for the screen and also enjoys writing words about the screen’s images.