Solitary Masculinity

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #142. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Finding deeper meaning beneath the virtual surface.

———

The 2018 drama, Leave No Trace, starts off following a man named Will and his daughter Tom, a houseless family squatting in a state park outside of Portland. Will is soon revealed to be suffering from the effects of PTSD due to his time in the military. We never learn much about Tom’s biological mother, beyond her sorrowful absence from their lives. Will is Tom’s sole and remaining caretaker; and he attempts to be a good one, the only way he knows how.

Likely drawn from training he received in the military, Will rigorously runs his daughter through a series of drills where they attempt to hide in the nearby underbrush at a moment’s notice. The aim of these drills is to escape from being detected by authorities (or any phantoms from Will’s ever-present mental distress). Yet when the authorities do come, his strategy immediately fails and they are discovered. Even though Will is the highly trained vet, he is the one who is found first. His impressive routine is revealed to be pure illusion. As paper thin as the mask he wears to hide the pain of surviving in the world with his impairments.

By the end of the film, Will’s self-destructive attempts to live apart from the world are clearly revealed to be manifestations of this pain, this ever-present dread. It’s his daughter Tom, who continues to try to bring them into potentially friendly and supportive communities. It is she who attempts to draw him out of isolation; to save his cursed soul by bringing in the warm, messy energy of human companionship.

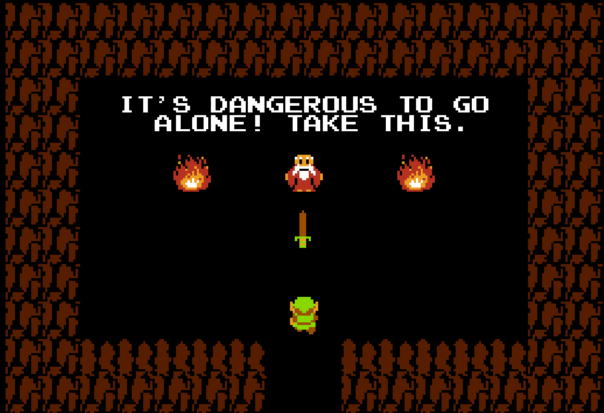

Will’s anguish, wrapped in solitary, prepper-style know-how feels eerily familiar to the masochistic “git gud” approach which has long plagued videogames. When the old man in 1986’s The Legend of Zelda tells the player that “It’s dangerous to go alone,” he does not then offer to accompany us. Instead, he gives us a sword, a tool with which to master nature, while remaining utterly isolated. During the intervening years, this has become the normative mode taken by most games: learn self-reliance, learn how to dominate these worlds. Don’t ask for help, do not look for comfort. Get good, or die trying.

When gamers belittle calling in co-op companions to defeat a particularly difficult boss in Dark Souls, when we refuse to look up readily available guides for complex Destiny 2 raids, when we laud toxic streamers like Ninja who are nevertheless talented at playing games, when we complain that critics and reviewers aren’t competent enough to have a trustworthy opinion about the games they’re covering, we allow games to remain stymied in the realm of the solitary, hollow victory. We cherish confidence and raw talent, patience and indefatigability, we kneel at the feet of the man who can beat Dark Souls with slices of pizza, or the one who’s played ten thousand hours of Diablo 3.

But like Will in Leave No Trace, stubbornly trudging away from communal safety into the cold, unforgiving wilderness, this performative desire towards pristine excellence can often come from a tortured place, born out of loneliness and insecurity. Struggling alone with just your hard-won skills and long list of stringent routines to keep you company provides a sense of mental security that is too easily threatened by other people and other systems of meaning that don’t revolve around high scores. When it’s just you and a handful of knowable variables, there isn’t anyone else to disappoint, no one to need to open up to or hold space for. Boasting later about your primacy, coined evocatively by game platforms as “achievements,” provides a veneer of socialization that allows you to stay buttoned up and walled off behind the medals and trophies immortalizing your lonely adventures.

Even as games have become more online, more social, more connected, our approach to them tends to stubbornly remain just as internally focused. We connect online by fighting our way to the top of arbitrary leaderboards, grinding for hours to earn a rare costume or emote we can proudly display and lord over others. In social games we are brought together while remaining in our own individual bubbles of isolation, still imprisoned within our own worlds and routines.

To the wounded, the world can easily seem like an unfriendly place; a challenge which must be mastered before it can be faced. So much of life seems to be about reacting to these wounds, building up walls, escaping into the woods, hiding from the oppressive forces which seek to control us. Sometimes it feels like we will never have the space to heal. Games with their knowable tools and routines can stave off the despair, for a while. But it’s in community and solidarity that we might find a surer path toward hope.

———

Yussef Cole is a writer and a visual artist hailing from the Bronx, NY. He makes images for the screen and also enjoys writing words about the screen’s images.