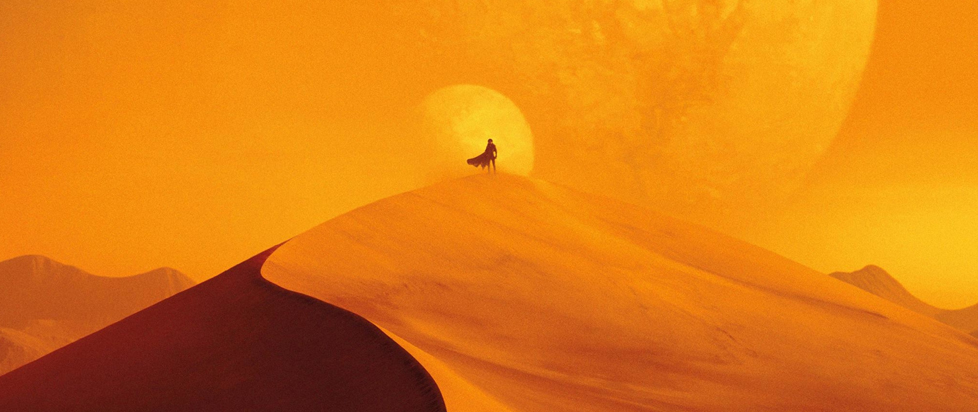

What Lies Beneath The Sand

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #145. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Reframing the boundaries of what is seen and unseen…

———

What I love most about fiction writing is its ability to dive deep into the complex interior lives of my characters. Within this pursuit is a drive to illustrate such things as the contradictions, fears and desires that influence the characters to the reader. What makes these moments of interiority so powerful is their ability to explore not only how we navigate our complex realities, but also what for? These things can be plainly stated within the confines of the pages, but when it comes to adapting them to the screen, many compromises (as they should) must be made.

It’s no surprise then that Hollywood has struggled for so long to successfully adapt a complex, sweeping novel such as Frank Herbert’s Dune. And yet, Dennis Villeneuve – one of our current moment’s best directors at adapting dense science fiction narratives for the screen – has attempted to do what no one has succeeded in doing thus far: capture the depths of what lies beneath the sands of Arrakis.

***

The novel Dune and I don’t get along.

I’ve tried reading it at least five times over the course of my life. After all, it’s hailed as one of science fiction’s greats for those looking to sink into a sprawling interplanetary epic that so many subsequent properties drew inspiration from. But to me, at a line-level it has always just read boring as hell.

Despite those feelings, I was excited for Dune (2021) because I’ve been a longtime fan of Villeneuve’s films. I saw Blade Runner: 2049 three times in theaters, and have yearned for him to release the four hour cut of the film that supposedly exists. Arrival feels like one of the freshest science-fiction films I’ve seen in decades, and across his growing catalogue of films, it’s clear he cares deeply about showing how our interior thoughts interrupt, influence and complicate our daily lives.

Upon watching the film, I’m struck by the severe lack of this introspection displayed in Villeneuve’s adaptation. I’m no expert on Dune, but I spent some time learning about the intentionality of Herbert in creating this world, as well as read through some of the early chapters of the novel to understand the liberties taken to adapt this dense tome into something enjoyable for a general audience to watch. But it seems to have missed the mark on some notable moments.

To my surprise, the novel spends a great deal of its early chapters delving into the anxieties of characters like Paul, Jessica, Gaius Helen Mohiam and the Harkonnens upon the great shakeup of House Atreides taking over control of the desert planet Arrakis. Something made clear from the start of the novel is Paul’s keen curiosity in the inner turmoil surrounding his birth, his positionality amongst his family House, the greater galactic political moment and also his role as a young man coming into awareness of the complex spider web of political, socioeconomic and interpersonal conflicts that await him after he sets foot on Arrakis.

***

Reading interviews with Herbert about the genesis of Dune, it becomes apparent just how important it is to keep one of his key anxieties explicated: charismatic leaders are predisposed to corruption. That charismatic leaders should be wrapped in caution tape. Herbert once said:

“The mistakes (of leaders) are amplified by the numbers who follow them without question. Charismatic leaders tend to build up followings, power structures and these power structures tend to be taken over by people who are corruptible. I don’t think that the old saw about ‘power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ is accurate: I think power attracts the corruptible.”

This idea is sussed out and explored overtly in the early chapters of Dune the novel, with Paul even as early as chapter one pondering if he is the human personification of the gom jabbar – a needle dipped in a deadly meta-cyanide poison. I found this choice to start the novel with the protagonist questioning what his role will be with his growing power, not only interesting, but also a key insight into the themes and ideas the novel will explore.

Villeneuve’s approach does hint at some of these ideas, but often, they are just that. Hints. Murmurs that flatten and even obfuscate some of these key ideas in ways that are not only strange, but beg the question: what are adaptations for? And how does the message of this work change when presented subtextually?

At the start of the film, we hear Chani, portrayed by Zendaya, narrate over the backdrop of Arrakis; its most notable features, Spice Melange, floats listlessly in the air, golden sparkles drifting in a daytime zephyr. She explains the history of Arrakis and its years of oppressive colonial rule by House Harkonnen in pursuit of harvesting Spice. She ends her narration pondering a key question: who will be their next oppressor? The film cuts to Paul Atreides sleeping, and I’ll spare you the rest.

This is an interesting choice, a welcome one at that, for those who are paying attention. But this key shift in perspective for how the world of Dune is introduced is quickly overshadowed with an overly simplified depiction of House Atreides preparing to depart for Arrakis with characters like Paul, the Duke, Duncan Idaho, and more, all being given the heroes’ treatment.

While much care and precision are given to recreating the complex, alien worlds that Herbert dreamed up in the novel, with Villeneuve even quoting directly from the text, I can’t help but feel the narrative has been neutered a bit. Reduced to a good versus evil, colonists versus indigenous people tale without the complexity the story spends so much time building through its interior moments.

I find starting the story through Chani’s perspective a powerful choice for this narrative. It is a warranted change that seeks to deepen and uncover new possibilities for a text like Dune which, for all of its goodwill, is still burdened by the time period in which it was written.

But in this first part of Villineueve’s film, the same risks aren’t peppered throughout. Sure, we get other notable changes like casting Liet-Kynes as a woman (portrayed by Sharon Duncan-Brewster) instead of a man, but none are as daring as those opening lines, and Zendaya solely serves as a bookend to this film. An element in Paul’s dreams. A reverie of what’s to come instead of what is there.

***

I realize adapting a work like Dune as a big budget film is a losing battle. It’s a prodigious text and sprawling world, it has a ravenous fan base who’ve been let down in the past, and it’s dealing with complex socioeconomic, religious conflict, and inklings of antifascism. None of these things combine to make an easily digestible, billion-dollar franchise. I know that something’s gotta give. But I can’t help but beg the question, if we can’t realize the key pillars in the text, is an adaptation needed? Are we adapting works that were written in their intended form solely for sport? For money?

I think we all already know the answers to these questions. Adaptations at this scale are the product of the repressive creative environment we all must navigate. I just wish that if they must be done, that more risks were taken. This film shows that they can be, but the emphasis is pointed in the wrong directions (if you’d like an easy example, read chapter one of the novel and then watch how Villeneuve adapts the gom jabbar test and its aftermath).

When aspects like the clearly fascist imagery of House Atreides are left subtextual, or the omission of Paul’s complex anxieties around his potential hand in dooming the galaxy are left subtextual, it opens up the capacity for viewers to misunderstand what this work is grappling with. Misunderstanding or having a different reading of a text isn’t a bad thing, but are these particular themes ones in which we want viewers to take away the wrong message?

Don’t get me wrong, Villeneuve’s Dune is a fun movie to watch. The costumes are stunning, the world that Herbert dreamed up is fully realized, and most importantly the film pushed me to seek out the source material. But it’s troubling, to say the least, that in the Villeneuve Dune what lies beneath the sand is what we’ve known all along from its marketing push: a sandworm, churning through earth, producing more shimmering commodities for us to harvest.

———

Phillip Russell is a Black writer and podcast producer. His writing explores the intersections between pop culture, Blackness, and our connection to land and identity. Follow his work on Twitter @3dsisqo.