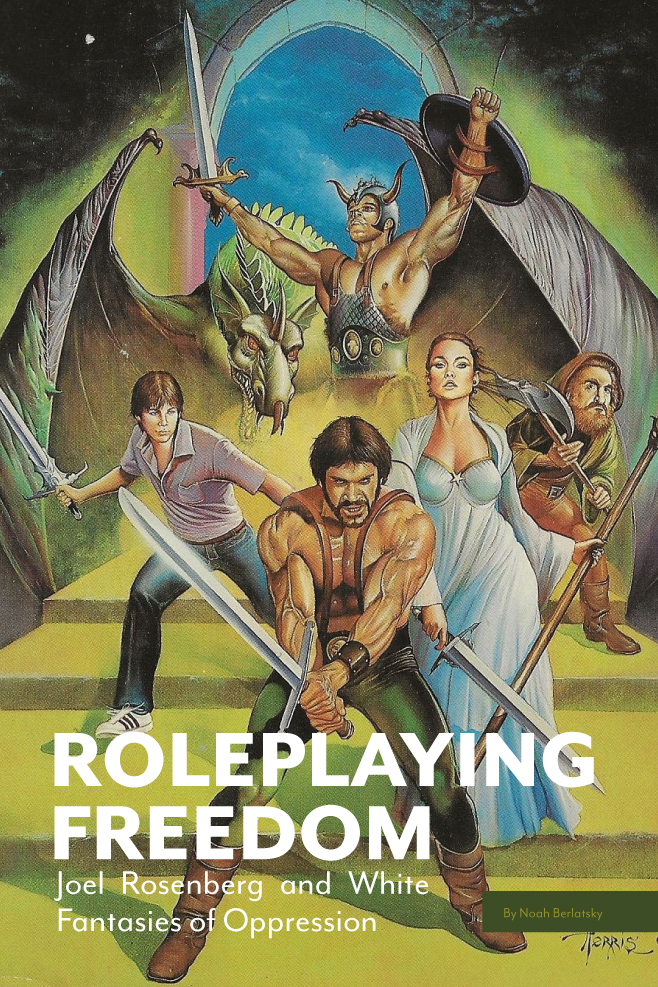

Roleplaying Freedom: Joel Rosenberg and White Fantasies of Oppression

This is an excerpt from a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #145. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

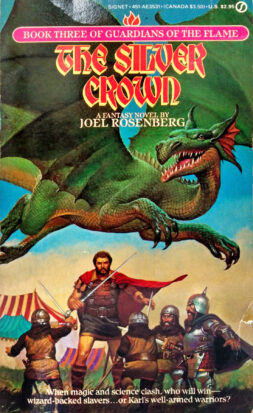

Science-fiction and fantasy author Joel Rosenberg (1954-2011) was a gun rights activist. He wrote a manual explaining how to obtain a legal handgun in Minnesota and was arrested when he wore a gun into the Minneapolis courthouse. In the current political landscape, this militant approach to the second amendment puts him on the political right. But his most famous series, the tabletop role playing game-influenced The Guardians of the Flame, is adamantly, passionately anti-slavery, focusing on systemic exploitation rather than on noble houses fighting off mysterious dark challenges to the status quo. In his focus on the plight of the lower-class, and indeed in his call for revolution, Rosenberg’s series seems firmly on the left.

So, which is it? Is Rosenberg a conservative or a leftist? The answer is probably more the former, with some ingenious interpolations of the later. Rosenberg cleverly embraces the rhetoric of freedom while using his fantasy setting to avoid an engagement with the actual history of unfreedom in the United States – a history which is inseparable from racism. Though The Guardians of the Flame prides itself on its sweaty, blood-soaked, proto-grimdark realism, it ultimately serves as a kind of conservative fantasy in which white people get to be the leaders in the fight for liberation. The series was not influential, necessarily, but it remains a well-thought through, impressively detailed map of the ideological landscape which fantasy novels and TTRPGs would do well to avoid when they try to engage with injustice.

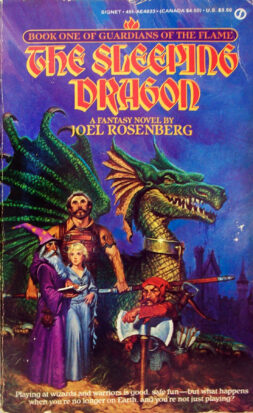

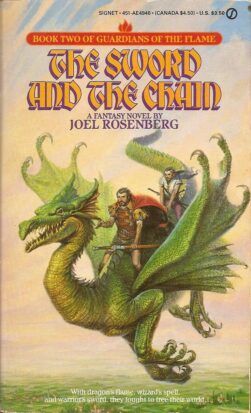

The Guardians of the Flame series ran from 1983 to 2003 and includes ten books. I’m mostly going to focus on the first few, since, as I’ll discuss, the series loses a good deal of snap as it goes on.

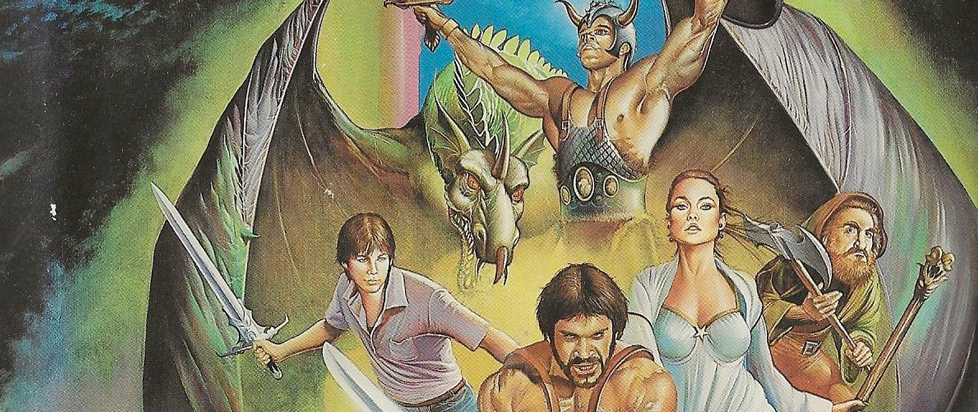

The first novel starts with a group of (all white) high school students playing a TTRPG just enough unlike Dungeons and Dragons to avoid copyright problems. Their game master, philosophy professor Dr. Arthur Deighton, is, as it turns out, a powerful wizard, and sends them into a fantasy realm where magic works and they all take on the bodies of their characters. Through the first book, their main goal is to return to their Earth. While trying to sneak past the dragon who guards the Gate Between Worlds, however, the party leader, Ahira the Dwarf (aka computer science major and quadriplegic James Michael Finnegan on Earth) is killed. The band has to return to the realm of magic to convince the clerics of the Healing Hand to resurrect him.

Rosenberg’s wife, Felicia Herman, said that Rosenberg wrote the series in part to show that gamers wouldn’t actually want to live in medieval times; “It was basically a million-word love letter to the industrial revolution,” she concluded. In many ways the series’ blood-stained realism anticipated that of Game of Thrones. Sexual violence is rampant; the women gamers are gang-raped in the first book. in the first book. Sudden death is omnipresent as well. Rosenberg even beat George R.R. Martin to killing off the main character mid-narrative; Karl Cullinane, the main point-of-view in the first several novels, dies in combat in the fourth.

The White Savior Character Class

For Rosenberg, though, the real ugliness of the fantasy world is slavery. The medieval-ish society is driven by rapacious capitalism and a booming trade in both humans and magical creatures.

The emotional climax of the first novel is a scene in which Karl discovers that the city of Pandathaway’s sewage system is an enslaved dragon named Ellegon. Chained in filth for three centuries, the creature is forced to use its flame to incinerate waste. Ellegon is telepathic, so he has the ability to make Karl experience the gagging smell of garbage, and his despair directly. Thus Karl, like the reader, is placed vicariously in the experience of the oppressed.

That vicarious experience is life-changing. Despite the danger from the Pandathaway authorities, Karl, who has always been an indecisive dilettante, decides to free the dragon. In doing so he finds his true passion and calling. Ellegon is confused, then shocked, then impossibly joyous as Karl wades through sewage to slash the chain around his neck, allowing him to rise out of the muck, and into freedom.

Ellegon flew off toward the north, now so high he was only a dark speck against the blue sky.

*Free.*

“Karl, why?” Doria asked.

He slipped one arm around her waist, the other around Walter’s as they walked away. “Because I never felt this good in my Whole. Damn. Life.”

*Free.*

That was faint now; did he hear it, or just imagine it? It really didn’t matter. Not at all.

*Free.*

We don’t know if the last “Free” is spoken by Karl or Ellegon. Ellegon’s experience of freedom has become Karl’s and transformed him. Before he leaves, Ellegon bathes Karl in fire, cleansing him and making him immune thereafter to the dragon’s flames – a kind of sanctification. As in a lot of Hollywood depictions of oppression, (Schindler in Schindler’s List, the good white South African in A Dry White Season, the FBI agents in Mississippi Burning, Lincoln in Lincoln) the depiction of liberation is less about those liberated, and more about the moral awakening of the white liberator.

In white savior narratives, the oppressed are generally presented as both incapacitated and dependent – they’re childlike. Not coincidentally, Ellegon, though he is hundreds of years old, is still a child in dragon terms. In later books, after Karl establishes a settlement and begins raiding slavers in earnest, Ellegon becomes effectively his adoptive son.

You might think that Ellegon would go seek out others of his own kind, and that perhaps the huge, fire-breathing dragons would take revenge on humans for enslaving their people. But dragons apparently have no family ties. Ellegon’s infantilization, and his prioritizing of his relationship to (white) humans over his own relations again parallels Hollywood portrayals of Black people like Sam in Casablanca or Mammy in Gone with the Wind. Ellegon is a retainer/mascot, who validates the morality of his saviors and betters through his loyalty. And just to drive the point home, Karl has a Black companion as well—a man named Chak, who Karl freed, who becomes his right-hand man, and who then sacrifices his life for him.

———

Noah Berlatsky is a freelance writer in Chicago. He is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948, from Rutgers University Press.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 145.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!