DISASTER PARADISE: at the Centre of the Miiverse

The Wii U is a party trick for people who don’t go to parties. The Wii U is the tea and coffee stand at a neighbourhood watch bingo night. The Wii U is the fourth page of an AskJeeves search. The Wii U is the last chairlift ride of a down-and-out alpine ski resort. The Wii U is the thousand-yard stare of the teenage ride operator at a children’s theme park. The Wii U is an eleven year-old boy screaming into his iPod Touch on a jerry-rigged three-way FaceTime call. The Wii U is the fourteenth hole of an indoor mini golf course in an abandoned shopping centre whose owners sold it to become the least liked members of their yacht club in Swanage. More than anything, though, the Wii U is a ghost town.

Haunting an unlabelled drawer in the least-used classroom of my lightly prison-resembling high school is one such party trick. We toy with it at lunchtimes, not unlike children poking an animal’s corpse, and for a while it feels as though we’ve made a new friend; its controllers goofy and childish, its library the classic Nintendo-branded soup of wild ideas and master craftsmanship. Nowhere is this otherworldly identity more apparent than in Nintendo Land, itself a now-abandoned fictional theme park with single-digit visitors. We laugh at one-versus-four minigame Mario Chase, not just because of its flawless cat-and-mouse level design but because whoever’s playing as Mario has a live facecam broadcasted at the worst possible angle. Funniest shit I’ve ever seen.

We laugh for a little longer: Metroid Blast is a similarly nostalgic version of Halo splitscreen for people with strict parents, while Animal Crossing: Sweet Day allows us to make the same “it’s the pigs!” joke every time the anthropomorphic cops show up. But eventually the fun dries up, and we move on to newer, less Early Learning Centre-ish things. It’s at that point that the Wii U’s true form is revealed.

Without friends, there’s nothing else to do in Nintendo Land. Half of the twelve games are designed specifically with one player in mind, and yet none of these “rides” are in any way fun. You exit the game and, after a way-too-long, uncomfortably silent loading screen, are returned to the system’s main menu. A barrage of icons spread loud on a barren grid, once press conference-touted revelations now lying untouched. You open one up; it was shut down three years ago. You close it back down again. Of course no-one uses Wii U chat anymore, idiot. Many are able to point and laugh at such an obvious failure, but for those strapped to the console like kids at a McDonald’s playground, the system takes on an altogether more intimate persona. To wander the Wii U’s virtual streets is to find yourself lost in a museum of misconceived ideas and arrogant assumptions, a disaster paradise for all willing to see. It’s our own personal ghost town.

We remember the music most. Almost every app has its own distinct track, sometimes more, and while the beloved shopping and Mii-making channels are as unnecessarily sick as ever, much more is composed simply of ambient jingles. The sparse, jazz-like chords and understated synths don’t seem immediately memorable, yet here I am years later, sobbing to a YouTube playlist and “oh shit, I remember this one”-ing the Wii U Friends List theme. Console music often seems to hold such a power over us, perhaps thanks to its train-like purpose as a space between games rather than being a loud personality itself: no-one buys a Wii U to listen to the menu music, but after playing so many different games we can’t help but feel fond of it anyway. Even the Wii U’s start-up screen feels oddly comforting, as a stampede of Miis rush to greet us, their footsteps the jingles of the music in the background. I say greet us. Everyone in the so-called “Miiverse” is dead now.

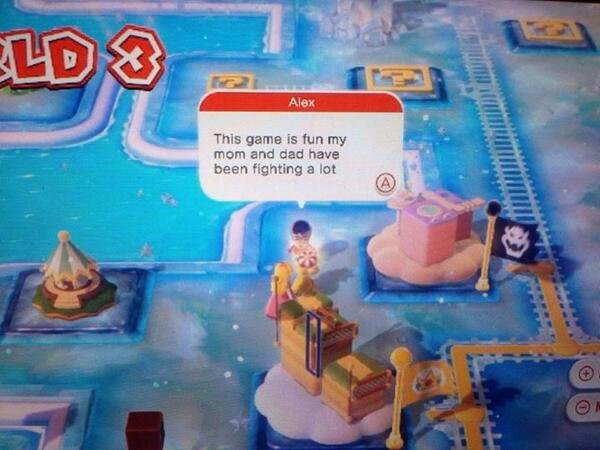

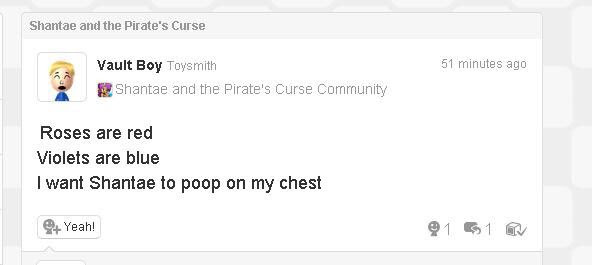

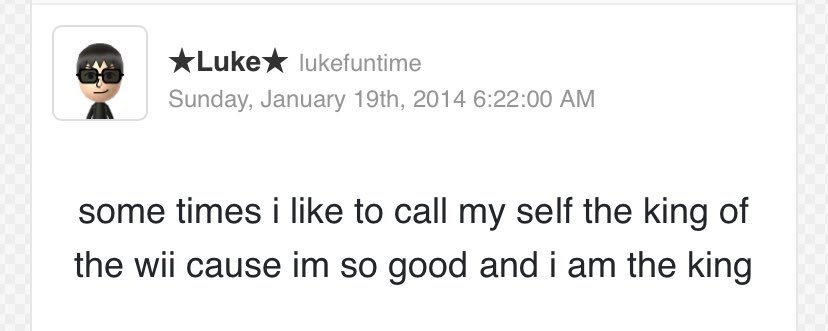

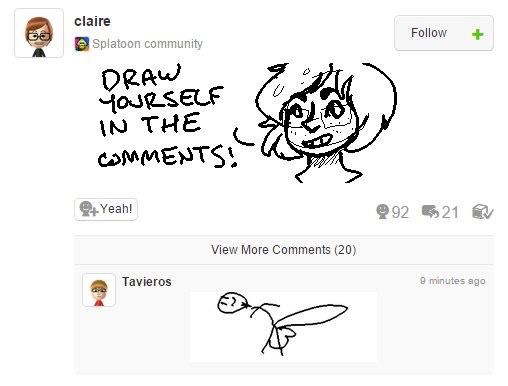

Miiverse is Nintendo’s candyfloss, white-picket-fenced vision of a social network. Sorry, was. Like so much of the Wii U, Miiverse’s emerald-green message boards have been taped off for years, a generic error message flatly reminding us of its indefinite closure and the start-up stampede replaced with lifeless replica dolls. Of course, we can still find signs of Miiverse’s life strewn in pockets of the “real” Internet: its myriad background songs are all on YouTube – accompanied by wistful notes from its (very few) users – and great effort has been made by said fans to archive and enjoy the very best posts. And Good Lord, the posts. Combining Nintendo’s boldly naïve premise – “What if we created a sanitised space for players to share their favourite moments from compatible Wii U and Nintendo 3DS games?” – with its bizarrely-strung userbase (let’s be honest, six-year-olds and twenty-six-year-olds) provided the perfect canvas for some of the most surreal, wildly inappropriate comedy of the Internet age, rivalled only by Xbox 360-era voice chat. Gamepad-scrawled dicks flew everywhere they wouldn’t be shot down by moderators, and quiet confessions of parents’ divorces bubbled away next to unassuming Mario levels, with viewers left legitimately unsure if what they had just witnessed was a joke from some internet jackass or a genuine cry for help from a small child. Don’t want a suspension for drawing a ballsack online? Simple! Just use the official double cherry power-up® stamp from hit Wii U™ classic© Super Mario 3D World™! Miiverse was art, and we are still wandering its gallery halls to this day.

But what we have now will never be the same as what we once had, and we’re kidding ourselves if we think otherwise. A few dedicated Twitter accounts could never replicate the sea of unfiltered gold, of children discovering themselves in the most awkwardly profound way possible. I played the updated Switch version of 3D World earlier this summer, and in many ways it’s the definitive version of the game: minor movement and control tweaks make the original levels shine, while the addition of online multiplayer and the new Bowser’s Fury section offer two different glimpses at the future of Mario. Yet for all the care taken to transfer the game onto modern hardware, something still feels missing. Where once was a flurry of comments from children / manchildren, there now exists an uncomfortable silence. There are no mildly concerning references to unhappy marriages, and there are certainly no Bowser balls. For those who never played the original, there may not be a visible difference – the game looks colourful and fun in the colourful and fun way Mario is legally required to be – yet those hints of humanity, those copious imperfections; they’re all gone. It’s a void.

So how do we fix this? How do we make sure these games are fully preserved, both in body and in soul? It’s not a simple question. With 1:1 re-releases of old games often seen as niche and unprofitable by companies like Sony and Nintendo, emulation has long been heralded as the only lifeline for players, yet technical issues and malware are rampant. Surely suffering through Super Monkey Ball 2 on a PS5 controller with save states through Dolphin Emulator wasn’t the designers’ original vision, and neither was buying that incredibly shit-looking remaster. So if emulation on modern computers is too buggy, and remasters on modern consoles are too few and far between, and neither method truly feels “right”, what can we do? Perhaps we can learn something from a certain parkour artist’s great-great-grandfather.

The quest for ever-increasing profits is not sustainable, nor does it create sustainable art. We are constantly upsold new video games through a drilled-in lust for whatever’s considered “next-gen”, and encouraged to drop our old games like toys from a distinctly non-ray-traced pram. Nintendo are famously guilty of such greed, and the Wii U’s desolate, liminal ambience is proof of that. Should we be grateful that such a strange failure of a system exists, or mournful of the corporate greed that led us here in the first place? It’s fun to poke around and laugh at the mistakes of a company in an era of such overconfidence, but it’s also hard not to think of the designers and engineers who worked so hard to create a box with so much potential, only to have their work thrown away for its more successful younger sibling. The all-or-nothing nature of capitalism often creates these spaces that exist in a perpetual state of limbo: the Wii U is a ghost town, not because no-one lives there but because its leftover advertisements and false inhabitants seem so desperate to prove otherwise.

From the attempted closure of the PS Vita’s vast digital library to the abundance of scalping and inflation in second-hand markets, it’s been made clear time and time again that those in power only appreciate games as far as they can sell them. If video games are truly an art form on par with film and theatre, as we have been reminded at their every award show and press conference, we need a way to archive games in a way that preserves not just their form but their spirit. With public domain laws rendered useless by games’ tiny history, we need to think bigger. Instead of obsessing over how we can recreate the Avengers, why not learn instead from Hollywood’s famous Paramount case, where governments overthrew draconian businesses by preventing a monopoly over all stages of production? In conclusion, rich people are once again to blame for everything.

It’s easy to despair over money’s unrivalled ability to ruin everything it touches (at least it’s not ruining human lives this time), but the story doesn’t have to end there. Industry-wide shifts (especially those that hurt profits) will take the kind of time and legislation kept largely out of our hands. But like any attempt at change, there are still some things we as consumers can do to encourage and protect cool artists and their cool art, as well as celebrate bizarre missteps like the Wii U. I’ve heard a lot of talk about video games having “fell off” in the last few years, and while the miserable cinema-chasing of Sony and its seems like it’ll continue for quite some time, there is still so much wonder to find – you just have to know where to look.

Go check out unfamiliar genres. Buy whatever weird shit you can still get, and emulate what you can’t. Seek out more diverse creators. Share your games with friends. Keep your old consoles around. Support weird, experimental hardware. Turn your Wii U back on from time to time and play Nintendo Land with your friends. Maybe that’s how Miiverse lives on.