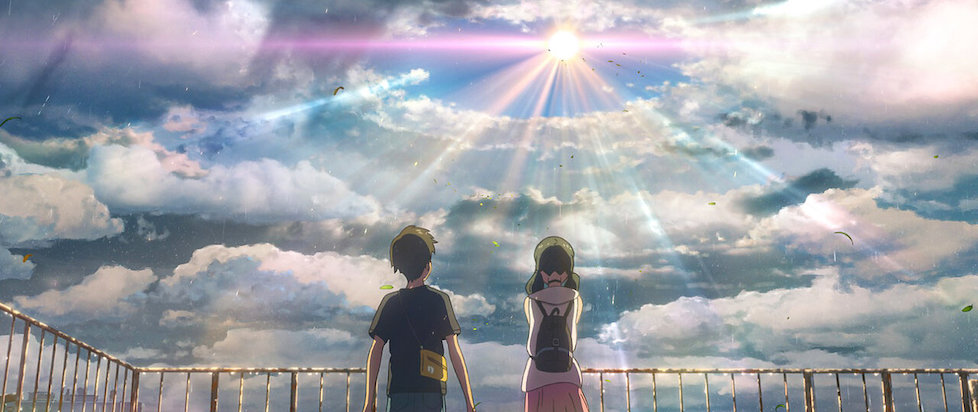

Sheltering Sky

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #142. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Peripatetic. Orientation. Discourse.

———

Makoto Shinkai knows how to tell one story, and he’s gotten really good at animating it. It’s a sekaikei, a genre of storytelling that combines “apocalyptic crisis and school romance.” The themes: grief, irreconcilable loss, youthful naivety, a first love, heterosexuality (and that is a theme) and the collapse of the Symbolic. These are conventions of the genre too, of which Shinkai’s early mecha OVA (Original Video Animation) Voices of a Distant Star is considered a seminal work.

A neologism that literally translates to “world type,” sekaikei emerged in the late ’90s and early ’00s in response to Neon Genesis Evangelion and concurrent events that shaped the apocalyptic zeitgeist of Shinkai’s cohort. Motoko Tanaka writes:

“Sekaikei works deal with situations in which the foreground (love between the always male protagonist and the heroine) is directly connected to the background (apocalyptic crisis and the end of the world) without the mediation of the middle ground, such as communities and societies.”

While Evangelion’s dissociation could be read as depression in the West, sekaikei captures a much more localized retreat from reality know as hikikomori that had not yet blanketed the young otaku of Japan. And it is in this, the genre’s Lacanian collapse, that such works would grip American audiences in our own latent dissociation. [1] Yet as the nature of expression continues to evolve in the compounding apocalypses at the end of history, confrontations with hikikomori have drawn ire in both cultures.

Working with the conventions and thematic interests of the genre, Shinkai’s [2] 2019 film Weathering With You met another form of resistance: unintelligibility. [3] While the apocalyptic zeitgeist of anime post-3.11 [4] is being actively theorized, there’s evidently a strain texts critical of the prior decade’s apocalyptic imagination. These works, what I would call here post-sekaikei, are similar in form. They share conventions and thematic interests and are further influenced by the prescience of Evangelion, this time as the Rebuild of Evangelion. But post-sekaikei are not concerned with the same content as before.

With(out) the Symbolic, (post-)sekaikei texts elude easy narrativization: characterization becomes the embodiment of compounding metaphors, plot as a series of sequential themes, logical progress gamified. Even the seemingly straightforward plots of Weathering with You and its sister film, Your Name, operate beyond the literal. In an essay published last month, Shinkai writes of the films exegesis: “Something is going wrong. / The World has turned weird.” The lines evoke a verse of Mina Loy’s: “The past has come apart/events are vagueing.” To appreciate Weathering with You is to see a subversion of the escapism that had been sought in sekaikei, a reckoning that reconfigures powerlessness into agency.

RADWIMP’s (quite literal) theme song [5] begins with a supplication: Is there anything else that love can do? We could rephrase the question: What if the Imaginary can no longer filter the Real, the foreground supports the background, love saves the world? A later verse continues: “All love songs had been sung/Myriad movies had their stories told/you and I were born in such a wasteland, and yet.” And yet. The sentimentality of empowerment pop is rooted in the material struggles of the films characters living through austerity. Neither the soundtrack nor its film invokes some ambiguous sense of universality, but recognize hierarchies between characters who find solidarity through shared struggle rather than shared identity.

Hina and Hodaka are clearly positioned at the end of history, where conventional – generic – forms of meaning making have broken down. Further, the pair are located on the periphery as Hodaka begins the film traveling to the capital. Both are young (dependent), gig workers (poor), housing insecure (insecure). When Hodaka eats only because of the sheer munificence of Hina, his food is delivered in the intricately replicated branding of disposable food containers. Neon billboards illuminate the raindrops of the Tokyo skyline has he navigates a city hostile to homelessness. At his “job,” he works with the very recognizable electronics on my own desk.

Advertisements and branding are a part of the spectacle that CoMix Wave Films spent thousands of hours animating. All of it highlights the alienation from community – from the Symbolic – that has accompanied the central apocalypse of this specific film: climate change. Yet despite being bookended by Hodaka’s doubts that Hina ever had some magic ability to alter weather, that it was all just delusion, chunibyo, American critics seem to insist that it is the two children who condemned the world or are at least partially at fault, when as a sunshine girl, Hina is as agential as every tween climate activist trying to carve out a less apocalyptic future on what habitable land remains on Earth.

Shinkai writes: “For the young audience, the people for whom we are supposed to be making films, this is a world in which they never had a choice. Before they could have a say, the world was already going crazy.” And yet despite inheriting a world destroyed by inaction, it is the young pair who, in choosing to love at the end, actively choose the world before them. In the face of our reality, the love that perseveres is not the same that once was. Their supplication answered: there is so much more to do.

[1] While Evangelion is itself a recurring object of fascination in the column, the previous entry of Always Autumn could be understood as an exploration of two contemporary sekaikei and the shortcomings of the genre today.

[2] I refer to Shinkai alone in this text as he has a clearly defined thematic interest throughout his filmography. Some of Shinkai’s earliest animations were made entirely by himself, and the difference hundreds of specialists makes clearly shows. That said, Shinkai is still known for being hands on with (read: controlling over) every aspect of his productions.

[3] These criticisms reflecting the imperial violence’s of the international mediascape Yuko Nishimura writes of.

[4] 3.11 refers to the triple disaster of the March 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and the ensuing Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.

[5] There are three translations of the song I have pulled from: the English version, an English translation of the original version, and the on-screen translations used in the theatrical showing (these do not appear on streaming).

———

Autumn Wright is an essayist. They do criticism on games and other media. Find their latest writing at @TheAutumnWright.