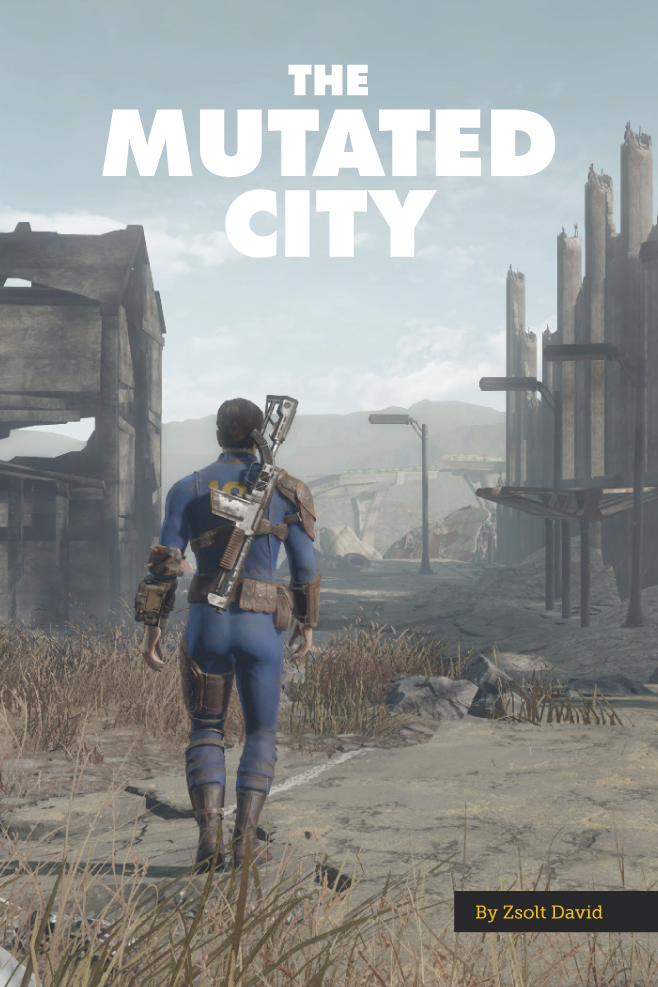

The Mutated City

This is an excerpt from the cover story of Unwinnable Monthly #142. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture is often considered according to its function of providing space to fulfill needs. Giving shelter against harsh weather is one such need, one that comes after raindrops drench us with cold water, then and leads to discomfort and illness. Social gatherings are similarly preceded by events that make them characterized as needs. As these affect all humans, they are taken to be collective needs that need fulfillment. Civilizations thus built houses to fulfill these needs which in turn created new needs. It’s one way to explain the evolution of architecture, as change from one abstraction to another and more abstractions of needs. Notice how I dropped the notion of collective. If architecture grew out from individual observation perceived to be common to all humans, then this fulfillment of needs for shelter, social gathering and so on, has to be commensurate with commonality and individuality. This clearly cannot be, since we were talking about plural needs and about commonality as a plural form of individuality.

To characterize this conjecture that takes place between the transformation from individual to that of individuals and from need to needs, in brief, while sticking to architecture, imagine a roof above your head. It stops the rain from falling upon you, and the sun from burning your skin. You may choose to cut a hole on this roof to let the sun and rain in, to warm yourself up, brighten the place you’re in, and to collect water for quenching your thirst. We may say then that the roof fulfills multiple needs and the hole was cut as a new need. Conceptions precede and arise from this observation, like light and dark in relation to sunshine, and water as it pertains to rain. We may also conclude that the roof leads to inventions that collect water and create these conceptions, and how it may change a person’s outlook of the sky. These statements make these ideas inseparable from architecture in how we experience them. Talking about architecture in context of a need is then a way of looking at architecture that relates an individual experience to individuals, and experiences that are reduced to experience under the assumption of commonality.

Videogames follow such assumptions about commonality and ordinary experience in crafting walls and furniture, for instance. We may say that a need for commonality connects them when a developer recreates places as ordinary images, similar to when a player interprets them as such by playing. In this sense, common notions connect these images to an experience, according to which one would locate videogame conceptions perceived to be common, like the controller, video screen, avatar and the first-person point of view. By relating these notions perceived to be conceptions, one thinks of them as a collection of ordinary notions, malleable like an image we make out to be a chair, a box, and so on, in order to call them as such. This makes talking about anything a game of approximation, where one guesses which notions are part of a statement and how they connect to one another.

To say anything of substance in this context, we shall locate these notions as glimpses of colors we may see from the corner of our eye during movement. As architecture drives our avatar’s swift movement in shooters, such as Doom and Quake, we shall think about ideas and notions as space for movement. In this space, thought appears as series of blurred images in movement that at once drives movement. In games about traversal, like Mirror’s Edge and Assassin’s Creed, prominent colors and edges of architecture drive our movement, akin to how an Idea with capital-I may influence our thinking. This renders architecture and thought to images where some shapes appear sharper over others. We could easily substitute these notions with the idea of need where one need blurs out other ones, like our own does over that of others’, hence the conjecture between individual and individuals. This blur of notions needs no alleviation, as one abstraction may become clearer over another, overpowering all the others temporarily, as a player’s movement does when mounting architecture in order to traverse them, when using walls as cover against bullets, and when using parts of a city as point of reference for orientation.

In this sense, architecture and thought represents a need and needs, one needs to overcome, which needs and “overcomings” create shifting images, some sharper over others, constantly changing as we think, forget, remember, and so on. One part of this line of thinking is that it turns the notion of knowing something into an idea of gaining power over it. But to get to know something completely, each facet needs to be uncovered, which isn’t possible, since forgetting and remembering creates cycles of images that unveil themselves as sharp and blurry. This is supposed to go on until every facet is unveiled to reveal this power-play. But blurry images become sharp as we think about them to the expense of sharp images that become blurry as we do not think about them. With this dual motion, thinking, remembering-forgetting and power-play remains touchable but forever out of reach. Like with the duality of need and needs, both remain hidden and unveil parts of themselves to obfuscate both by interpreting them as a collective need.

To move away from this individualistic mode of seeing images as source of power, an external stimulus is needed. Like a rooftop assembled above our head bursting out from the ingenuity of the collective to open up new perspectives.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 142.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!