Simulando

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #141. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #141. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Personal marks scattered through time.

———

As I grow older, I’m beginning to realize how out of place I feel compared to people of my age. Some have been studying a career ever since high school ended, which is something I’ve tried and failed to complete across three different instances. Others have a nine to five job, which actually ends at five and doesn’t tend to carry on to the weekends. When I tell them about my dependency with emails or smacking my head against the wall with an overdue draft, it sounds alien in comparison.

Sure, all careers and jobs are different, and we’re all juggling personal stuff in between as well, making each of our life experiences unlike everyone else’s. But for me, it goes beyond that. It’s about identity. This is the year where I realized how I have been neglecting part of my culture, and part of my own self, in order to be accepted in international lenses.

Ever since I took the decision to write exclusively in English, everything else in my life gradually shifted towards that goal. My Twitter account, which back then was used to follow and joke around with local friends, got a sudden language switch. From there, it slowly moved from an intimate environment where I wasn’t interested in how many likes or retweets I’d receive, to a professional account where seeing a tweet in Spanish only happened a couple times a year at best.

This shift became present everywhere else afterwards. Anything from my PC to my phone or any app I get to use is now in English. It’s not something that bothers me, mind you. I always loved the language, and pretty much everything I’ve learned has been from pure practice and constant use. But it’s the kind of thing you get so used to that it’s only until a friend points at your phone and asks why you’ve switched the language that it begins to sink in.

Friends, too, changed. I had known a couple international folks beforehand, mainly through Steam or forums, but colleagues and actual friends were rare until I started seeking circles outside of my country more often. Over time, I strayed from a few friend groups here. But I didn’t see this absence as a problem. I had found new people elsewhere, even if they were a hundred thousand miles and dollars away from me.

I was achieving my goal, in a way. I had always consumed media in English, especially music and videogames, so it felt natural. I finally had written samples to share in pitches, slowly moving up the freelance journalism ladder and making myself known. I was gaining Twitter followers from the US, the UK and so many other places that I could only aspire to visit someday. And then I went ahead and made those aspirations a reality, switching off Spanish almost entirely for entire weeks at a time.

But then again, it took the push of a friend to realize I was abandoning a big part of myself in tailoring every aspect of my life looking at the outside.

Back in 2002, when I was about five years old, a TV show called Los Simuladores (The Pretenders) came to life from the mind of Damián Szifron. It told the story of a group of con artists who created fake personas and scenarios to help people in need. But, interestingly enough, the people starring in each episode were less of cinematic characters and rather people you’d find on the street, or that you had probably stumbled upon before already. A kid who needs help in his exams, an employee with a sexist boss, the terror of a young woman who is introducing her messy parents to her boyfriend’s rich family for the first time.

It’s a well thought out premise elevated by a strong cast that only gets better over time with guest appearances. Episodes can be extremely funny as they can be serious in nature, often exposing problems that still linger to this day. It was a success, becoming a cultural hit that continues to be referenced, rewatched and respected by many. But for the longest time, I purposefully ignored it. I undervalued its importance because it was a local show and didn’t give it the time of day until a friend encouraged me to watch it.

Well, reader. I had been missing out big time, to say the least. With each passing episode I was surprised at the script, which is strangely timeless, and how well developed the characters were, each with a distinct personality. But the aspect that grabbed me the most, and the one I still can’t shake out of my head, is the warmth and attention to the details of what makes our local culture so special. Hearing slang so frequently made for incredible jokes, of course, and it reminded me how important that can be to someone’s identity.

Well, reader. I had been missing out big time, to say the least. With each passing episode I was surprised at the script, which is strangely timeless, and how well developed the characters were, each with a distinct personality. But the aspect that grabbed me the most, and the one I still can’t shake out of my head, is the warmth and attention to the details of what makes our local culture so special. Hearing slang so frequently made for incredible jokes, of course, and it reminded me how important that can be to someone’s identity.

Back in 2019, one editor from the UK I’ve worked with recommended a book to me. It was from the Argentina author María Gainzo, called El Nervio Óptico (The Optic Nerve). He was surprised at the timing of my emails since he had just started reading the translated version and was very fond of it. So, I picked it up a couple weeks later in a local bookstore and, for the first time in forever, I went for the Spanish version. And I’m glad I did.

Much like Los Simuladores, the book is built on local colloquialisms. It was pleasant to read Gainzo eloquently talk about her love of art and the stories that her passion and career have left behind over the years in a language I could recognize in my neighborhood streets. I mentioned this to the editor, trying to picture a possible translation of words and phrases that are so unique to us. He said that while the edition was excellent, it sometimes felt bloodless for this very reason, and that he would love to be able to understand the original intentions. It’s something that has stuck with me, considering how much of my life I’ve spent learning to do just that with English.

I’ve had a few other cultural existential crises in recent times. I remember this kind woman working at a store in LA who switched over to Spanish after reading my ID, and being taken aback by such an unexpected, yet memorable exchange that must have lasted no more than a minute. A couple acquaintances of friends of mine showed me the same courtesy, and I was always left with a smile on my face that endured throughout the rest of the night – a smile that is now present as I’m writing this, too. I’m not sure if it mattered to them whether or not their Spanish was good enough to engage in conversation with me, but it was the unconditional gesture that meant the world to me.

I also remember stumbling upon my words as I tried to ask a woman in an H&M whether or not they had a shirt in a bigger size. It was a short, straightforward question, but I got nervous either way. She quickly noticed it and told me, “Oh, it’s okay,” in a gentle manner. I stopped for a second on the spot and thanked her for it, before recovering my breath and asking the question.

I’ve always felt bad about not having a native English accent. There are days where I listen to friends, or even people I interview for work, speak and wish I could sound just like them, with such natural grace. And I’m gonna continue pushing towards that as a goal. But I’ve learned to stop being ashamed of my own accent. It’s part of what makes me who I am, and a constant reminder of who I will always be, regardless of whether or not I’m still living in Argentina in the future. The fact that it’s something unique to me should be worthy of celebration, not humiliation, either self-imposed or pushed by others.

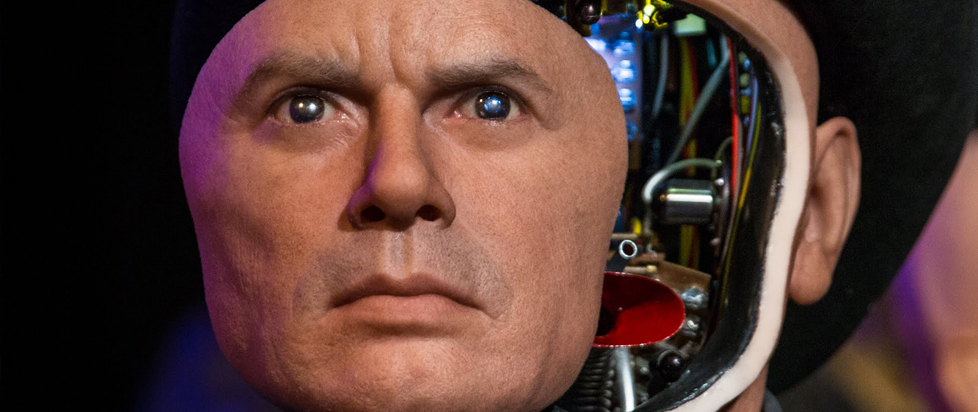

After Los Simuladores, Szifron directed multiple local movies (one of the most noteworthy ones being Relatos Salvajes, or Wild Tales in English), but his upcoming film Misanthrope does not feature a Spanish title, nor Argentine actors, this time around. I can’t imagine how proud he must be of directing a movie with an international cast of actors, or that his work has been noticed by the big names of the industry and is now being recognized on a bigger scale. I’ve no doubt that this film will mark a new step in his professional career. But I wonder if he’s having similar conflicting feelings about what it means to leave a part of himself behind in the process.

Watching the show’s final episode was cathartic for many reasons. Many on-going narratives culminate altogether in wonderful ways, and the bonds between the characters and the one we as an audience have gained are tangible. But I was also happy and emotional about having enjoyed the show so much, and what it meant to me. It brought me back to my customs, my childhood, and every person I know who was also born here whom I had been neglecting in one way or another – including myself.

I don’t know where my career will keep on taking me in the coming years. Considering the economic instability of my country, as well as many other issues, it’s clear that I won’t be spending the rest of my life here. And sadly, I’m not the only one who has made this decision. But until then, I want to enjoy the things around me as they were initially intended, and stop being afraid of expressing myself as the Argentine that I am.

There will come a time when hearing Spanish will only occur as short, unexpected gestures from kind people returning the courtesy. That thought feels, perhaps for the first time ever, scary. But it’s reassuring to know that I won’t be pretending to be someone else when that happens. Voy a poder dejar de simular aunque sea por un momento.

———

Diego Nicolás Argüello is a writer from Argentina who has learned English thanks to videogames. He also runs Into The Spine and is objectively bad at taking breaks. You can catch him procrastinating on Twitter @diegoarguello66.