Senegal

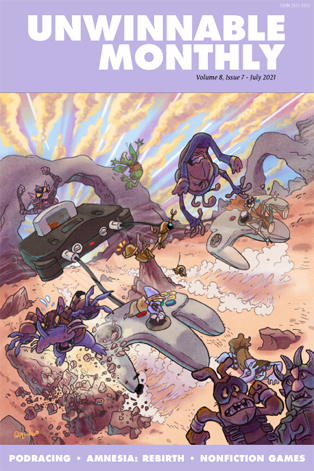

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #141. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #141. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Globetrotting through media.

———

Borom Sarret

In Sembené’s first film he focuses on the day of a wagoner in 1960s Senegal. Each new person he picks up has their own story. It’s not something which is dictated or declared to you, but through the performances and small amounts of dialogue you get enough to paint a picture of them. When you put these pieces together, alongside a very clever soundtrack, you are able to get a picture of what Senegal was like in the few years after the end of (formal) colonialism.

I couldn’t help but wonder what the days of a few of these people looked like after they left the wagon.

Fatou

Fatou sat by the river to wash her clothes. Years ago, she could have walked the path here with ease. Now the stones dig into her heels and the dust clogs her lungs. She wished she could pay that kind boy, who has taken her here whenever she needed, but her son was in the city and her daughter was in France – neither had been able to send money back to her. So instead, an old woman now, she relied on the generosity of strangers.

Her train of thought was disrupted by the joyful shriek of a small child playing in the rushing waters. Maybe tomorrow holds something better for them, she thought, we are veterans of the old new world, of servitude, of kneeling at the feet of ivory gods.

It could be different now – right?

The Businessman

Amadou entered the apartment and peeled off his painful battered shoes, then removed his jacket, placing it neatly in his near-empty wardrobe. He slowly slipped off his slacks, careful not to break the hasty stitches that held ripped fabric together. Next came the tie – his only tie. His fingers trembled as he pulled on the knot – he hadn’t eaten today. Unstable hands moved down to his shirt where dust and sweat coagulated to give an orange tinge. Soon enough it was on the bed.

What was left of him now? He moved to lie on the threadbare rug in his living room, without that suit was he just another colonial subject? Another Black pawn to be used and disposed of like the man with his wagon? “No!” he declared, voice echoing around his empty apartment. “I am more. My day will come.”

As they say – Impossible n’est pas français.

The Father

The day was fading and he was still here on the precipice – again. So close he could almost hear the whispers of the fallen – was that birds or crying? Was that a leaf or a tiny hand that grazed the back of his neck? The dust and the wind almost form a language of their own when he is here – maybe this time he could finally decipher it?

Once more he picked up his package wrapped in white, a bundle of warmth which had long run cold. Silence laid on those lips like a blanket and Senghor began to rock.

Atlantique

West Africa is no stranger to spirits and possession, Atlantique is an extension of that tradition of vengeful spirits returning to right a past wrong. What makes this ghost story fascinating is the context in which it’s set. It follows the teenage Ada (Mama Bineta Sane) after her lover Souleiman (Traore) leaves on a boat to Europe to find work and gets lost at sea. In the post-colonial Senegal we are presented with, the ghosts and echoes extend far beyond the men lost at sea. The blurring of lines between past and present, between the living and the dead, are ever present in the post-colonial Dakar we see in the film.

Various West African traditions believe in the power of spirits, particularly ancestral ones. The roles of these spirits can vary, but they’re often sources of guidance and power. Arguably their most important role though is to maintain the natural order of the world and reprimand those who go against nature and justice. This exists as part of a broader animism, the idea that things beyond humans have a soul/spirit. Whilst there aren’t many records of the colonial religious beliefs of the Wolof people (who the film focuses on) before Islamic colonialism, there is still an influence of these ideas on the way that Islam is practiced in Senegal. This influence with Atlantiques’ approach to a ghost/possession story which feels like a continuation of these ideas of spirits being a force of retribution.

Ibrahima Traore as Souleiman in Atlantics: A Ghost Love Story.

This pre-colonial animism is specifically present in Atlantique when it comes to water. The ocean, beautifully captured by Claire Mathon, is constantly shifting in its role. It is both a bringer of death, but also the bringer of opportunity – crossing it is the only way these men could provide for their families. It stokes fear in the hearts of the residents of this suburb of Dakar, but at the same time it’s full of love, with the spirit of Souleiman telling Ada “I saw you in the wave that took us… and your eyes never left us” – it was the ocean that brought them back. Water becomes the gatekeeper between the living and the dead, again tapping into this animism which dominated pre-colonial Africa and bringing it into the post-colonial. These ideas of the water as a place of death echoes the slave trade and the millions of slaves who died at sea. This is especially relevant given Senegal’s proximity to the “Slave Coast” where the most slaves were taken by Europeans. In a sense, the men who die at sea in Atlantique are similar. Whilst they aren’t being carried on slave ships, they’re still crossing the sea to serve European interests because they have no real other option. In an Africa which has been and continues to be strip-mined for resources by imperialists, braving dangerous waters to go and likely be exploited for cheap labor is the only route left available for many – whilst European nations let them drown. So, the colonial becomes mirrored in the post-colonial.

These colonial echoes are also visible in the landscape and architecture, like the old train tracks which run through the center of the suburb, almost cutting it in two. Most notably there’s the tower these men were building before leaving. Aesthetically it’s aping sleek, modern skyscraper aesthetic, akin to the Shard, rising above the modest buildings of the suburb and casting an imposing silhouette on the skyline. In trying to emulate this Western architecture, the indigenous Senegalese people are exploited – which is what leads them to leave and set off the events of the film. This mid-construction skyscraper almost becomes a Tower of Babel, reaching for this unattainable value of Westernness, as if trying to somehow recreate the ideals of the colonizer and make the misremembered colonial glory into something corporeal. So once again the influence of the colonizer echoes through to the present, with both the architecture and its associated exploitations being mirrored.

You can also see it in the language, where government officials and professionals still speak the forcibly imposed colonizer’s language of French, whilst the general population speak the indigenous Wolof. This seeps through to the names, with ‘Fanta’ and ‘Dior’ being (nick)named after Western products. Again, language is another sphere in which the specter of colonization remains ever-present. The language of the colonizer denotes professionalism, where the local language is seen as backwards, The West reverberates through language, whilst the pre-colonial still remains, again creating a present which is a complicated mix of the pasts.

At the end of the film, the men return home temporarily using the young women of the area as vessels. The one exception here is that Souilleman returns to Ada through the vessel of Issa. The two then dance and make love in the ethereal light of the bar, with the man Ada is dancing with/making love to on-screen repeatedly switching between Issa (the physical vessel) and Souleiman (the spirit possessing him). In this union, the dead and the living come together, the lovers are reunited, but this has to come through the filter of Issa.

When viewed through the lens of the colonial, this beautiful but uncanny scene becomes even deeper. There’s no way of bringing this ideal of the past back, even with the fiercest of love. But for a moment. For one night, the echoes of the past and the reality of the present combine. So, the pre-colonial can never return in its full form, but it can be drawn on and learned from. Its impact is still felt, its power is still real.

With this synthesis Ada can have her awakening, she moves from aimless teenager to an empowered woman – becoming “Ada to who the future belongs.”

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, podcaster and general procrastinator from London. You can find their ramblings @naijap-rince21 and their poetry @tayowrites.