The Seduction of Solitude

Content Warning: Brief reference to sexual assault, suicide attempt in fiction

Spoiler warning: Spoilers for 100 Years of Solitude, Cowboy Bebop, A General Theory of Oblivion, 2046, Infinite Jest, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Inside Llewyn Davis, Wolf in White Van

***

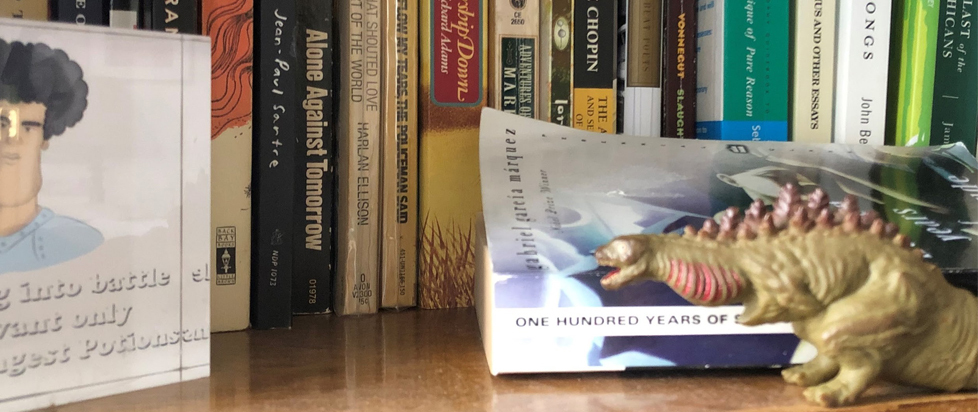

A month after my quarantine book club disintegrates, I read 100 Years of Solitude.

100 Years follows the Buendia family, each of whom inherits the family’s distinctive “air of solitude.” Though all Buendias find unique solitudes, each of their lives follow the same inexorable spiral toward it.

Though it’s easy for us to understand how the generations of Buendia repeat themselves, the family themselves never quite grasp the cyclical nature of their fates until it’s too late: “because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude do not have a second opportunity on earth.”

The Buendia problem wasn’t a lack of comprehension, anyway. Instead, it’s the universal problem for “races condemned”: Even if we could identify the patterns, what could we possibly do about them?

But maybe that’s just me. By the time I was reading Solitude, seclusion had started to lay bare some of my own inexorable cycles. Everything was starting to read the same way.

I notice it the first time a month into quarantine. I’m already watching Cowboy Bebop again, though I never get anything new out of it.

The crew of the Bebop respond to their traumas by retreating into roles. These clichés become their only means of imposing meaning on the world. The problem is, with only one story to tell, that story repeats itself. Spike wanders through life like he’s in a dream. When the story repeats, is it really happening? Or is it just all he can see?

The crew of the Bebop respond to their traumas by retreating into roles. These clichés become their only means of imposing meaning on the world. The problem is, with only one story to tell, that story repeats itself. Spike wanders through life like he’s in a dream. When the story repeats, is it really happening? Or is it just all he can see?

Cowboy Bebop is about what it’s like to come face-to-face with the patterns of your life and recognize yourself in them. But am I seeing that because it’s there, or is it there because I’m the one seeing it?

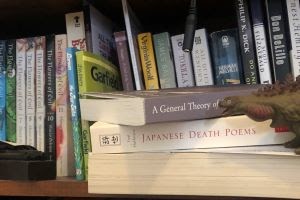

The last book my book club reads is A General Theory of Oblivion. We start it together; I finish it alone.

Oblivion follows a Portuguese woman named Ludo living in Luanda, Angola. On the eve of Angola’s independence, she walls herself inside her apartment. Though she ostensibly does this to escape the violence outside, we learn that Ludo’s agoraphobia predates Angola’s independence by years. It stems from an assault so terrible that she can’t confront it directly. She calls it “the accident.”

Oblivion follows a Portuguese woman named Ludo living in Luanda, Angola. On the eve of Angola’s independence, she walls herself inside her apartment. Though she ostensibly does this to escape the violence outside, we learn that Ludo’s agoraphobia predates Angola’s independence by years. It stems from an assault so terrible that she can’t confront it directly. She calls it “the accident.”

The “accident” created a shame inside Ludo that she believes people can actually see in her, and as a consequence the Angolans outside become “monsters” in her eyes. She walls herself away to hide from these monsters and begins writing her “voice” on the walls, composing “a great work on forgetting: a general theory of oblivion.” Of course, she doesn’t forget. But she begins to lose her eyesight.

The more Ludo rejects the outside world, the more her shame defines her. Ludo secludes herself to avoid seeing herself, but it backfires: alone, she becomes the only thing she can see.

Sometimes after I read a book I loved with a friend, I resent their input. I worry how it might affect mine. I wonder if there was a time when Ludo realized what she was really doing. I wonder if there was a time when all she wanted to see was herself.

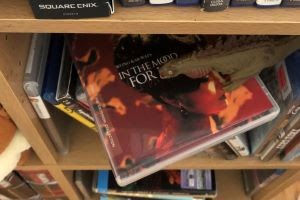

I make a podcast about movies with my friends, of course. During quarantine, we record a series on Wong Kar Wai’s movies. The last we cover is 2046.

2046 is a sequel to In the Mood For Love. It follows Love protagonist Chow Mo-wan in the years following his unconsummated relationship with Su Li-zhen. The more time passes, the less Chow is sure of what he had with Su Li-zhen… or who he is as a result. The doubt turns him bitter, then he turns that bitterness on others.

We disagree about the point of this sequel. My friends are crestfallen about Chow’s transformation and feel it undermines Love. I argue, too fervently, that that’s the point. Chow runs from the pain of who he is, so his defining traumas become more definitive, until he sees Su Li-zhen in everyone and everything. It’s meant to be as ugly as it is.

We disagree about the point of this sequel. My friends are crestfallen about Chow’s transformation and feel it undermines Love. I argue, too fervently, that that’s the point. Chow runs from the pain of who he is, so his defining traumas become more definitive, until he sees Su Li-zhen in everyone and everything. It’s meant to be as ugly as it is.

I wrap my argument with an incoherent assertion that “2046 is the Cowboy Bebop of movies” and represents the greatest maturation of Wong’s artistic philosophy: we must choose to believe in and live by what we feel, no matter the pain that comes with it. When I finish, there’s a characteristic pause, then someone changes the subject.

When I’m like this I remind myself of the first scene in Infinite Jest – a reference itself so loaded it exacerbates my shame. In this scene, Hal Incandenza thinks he’s speaking to an interview panel. In reality, he’s shrieking incoherently. Sensing the disconnect, Hal attempts to reassure the panel “I am not what you see and hear.”

In college, I learned not to tell anyone Infinite Jest was my favorite book. The admission allowed people to fit me into a role that was getting difficult to escape from – in their eyes or my own.

In college, I learned not to tell anyone Infinite Jest was my favorite book. The admission allowed people to fit me into a role that was getting difficult to escape from – in their eyes or my own.

I spend a lot of time apologizing to imaginary people about my affection for Infinite Jest. I don’t like to think about people seeing me as the lover of Infinite Jest; the annoying one on the podcast. I don’t want to be that person – which is to say, this person. “I am not what you see and hear.” I begin to understand what Ludo sees in walling herself off.

Right on schedule, this reminds me of another, equally cliched part of my cycle: Neon Genesis Evangelion. As my book club dissolves, I briefly consider watching Netflix’s new dub.

Eva discusses “the hedgehog’s dilemma”: hedgehogs want to cling to each other for warmth, but they risk being pricked by each other’s quills. Shinji Ikari is lonely, but he fears intimacy because of the vulnerability it requires. He fears judgment because he’s ashamed of his feelings.

Shinji’s subconscious tells him “The Shinji in Rei’s heart. The Shinji in Gendo’s heart. Each is a different Shinji, but they’re all the real Shinji. You’re afraid of the Shinjis inside others.” I spend too much time thinking about how other people see me. I fear the way they’ll judge that version. Worse, I fear that if I see that version, I’ll become him. So, in an attempt to “preserve” myself, I avoid him – and them.

Shinji’s subconscious tells him “The Shinji in Rei’s heart. The Shinji in Gendo’s heart. Each is a different Shinji, but they’re all the real Shinji. You’re afraid of the Shinjis inside others.” I spend too much time thinking about how other people see me. I fear the way they’ll judge that version. Worse, I fear that if I see that version, I’ll become him. So, in an attempt to “preserve” myself, I avoid him – and them.

Of course, judgment doesn’t go away just because I avoid people. I project and receive judgment quite easily alone – in fact, it’s a requirement. Isolated, my whole world becomes a solipsistic reflection of my own self-judgment. The seduction of solitude is certainty: I understand how I am perceived because I understand who I am. I’ve always been the monster I believe they see.

But maybe I don’t have to be like the Buendias. I don’t re-watch Eva in quarantine. Instead, I quit my job, restart my book club, and write this article. I convince myself it’s a victory – or at least that I can write it into one.

I don’t write many other articles during quarantine. The only other is about Inside Llewyn Davis.

I don’t write many other articles during quarantine. The only other is about Inside Llewyn Davis.

I write about how Lleywn’s performances within the film’s mobius strip-like structure reveal that, although Llewyn remains trapped in his head, he is able to reinterpret what that imprisonment can mean. Llewyn makes his music’s story mean something different, even though he can’t change what that story is.

I lose the plot a little at the end of articles. Endings are rarely as persuasive as the stories that precede them. Davis, Bebop, Oblivion, 2046, Infinite Jest, and Eva all have endings you could call life affirming. But those endings aren’t really what you remember.

My Llewyn Davis article is rejected without feedback. I don’t know if they disagree with my conclusion or just don’t like the way I wrote it. I’m not sure which I think either.

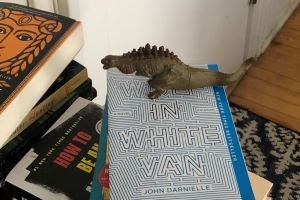

I ask if my book club wants to read Wolf in White Van, a book by my favorite musician, John Darnielle, with me. For some reason, they do.

Wolf is about a game designer named Sean whose imagination is so vivid it threatens to drive him to dangerous places. In a possible attempt to spare others from this danger, Sean shoots himself at 17.

Sean’s “accident” doesn’t entirely accomplish what he meant it to. Sean finds he still can’t save his players from their own imaginations, just like he couldn’t quite save himself. At one point, Sean admits, “I don’t really believe in happy endings, or endings at all.”

Sean’s “accident” doesn’t entirely accomplish what he meant it to. Sean finds he still can’t save his players from their own imaginations, just like he couldn’t quite save himself. At one point, Sean admits, “I don’t really believe in happy endings, or endings at all.”

Much as I’d like to believe my reading of Inside Llewyn Davis, I can’t help but agree with Sean. I’m sure when I leave my apartment, I’ll start feeling human again. I’ll get used to being perceived and convince myself not to feel ashamed about it… sometimes. But the promise of solitude never really goes away. It’ll stay in the back of my mind, lit up like an emergency exit, to offer me a version of myself I can be sure about.

I got into John Darnielle’s band The Mountain Goats at a very dark time in my life. Around that same time, one of my fellow podcasters gave me a figurine of the creepy, gestational first form of Shin Godzilla for my birthday.

Ever since then, I’ve been following two routines: first, I carry around Godzilla everywhere I go and post pictures of him with the caption “Godzilla.” For the past year, these have all been pictures of the inside of my apartment. Second, I find a new Mountain Goats “theme song” every few months and listen to it until I get sick of it because it reminds me too much of myself. My quarantine theme song is “New Monster Avenue.”

Ever since then, I’ve been following two routines: first, I carry around Godzilla everywhere I go and post pictures of him with the caption “Godzilla.” For the past year, these have all been pictures of the inside of my apartment. Second, I find a new Mountain Goats “theme song” every few months and listen to it until I get sick of it because it reminds me too much of myself. My quarantine theme song is “New Monster Avenue.”

Before playing “New Monster Avenue” at a concert once, Darnielle explained, “This song is about the feeling you get if you stay in your house too long and feel like you don’t relate to anybody at all. And you sort of resent them, but you’re certain they’re going to come and get you. I’m here to tell you you’re absolutely right.”

The song ends,

“Fresh coffee at sunrise

Warm my lips against the cup

Been waiting such a long time now

My number’s finally coming up

All the neighbors come on out to their front porches

Waving torches”