The Personification of the House

This is an excerpt of a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #140. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

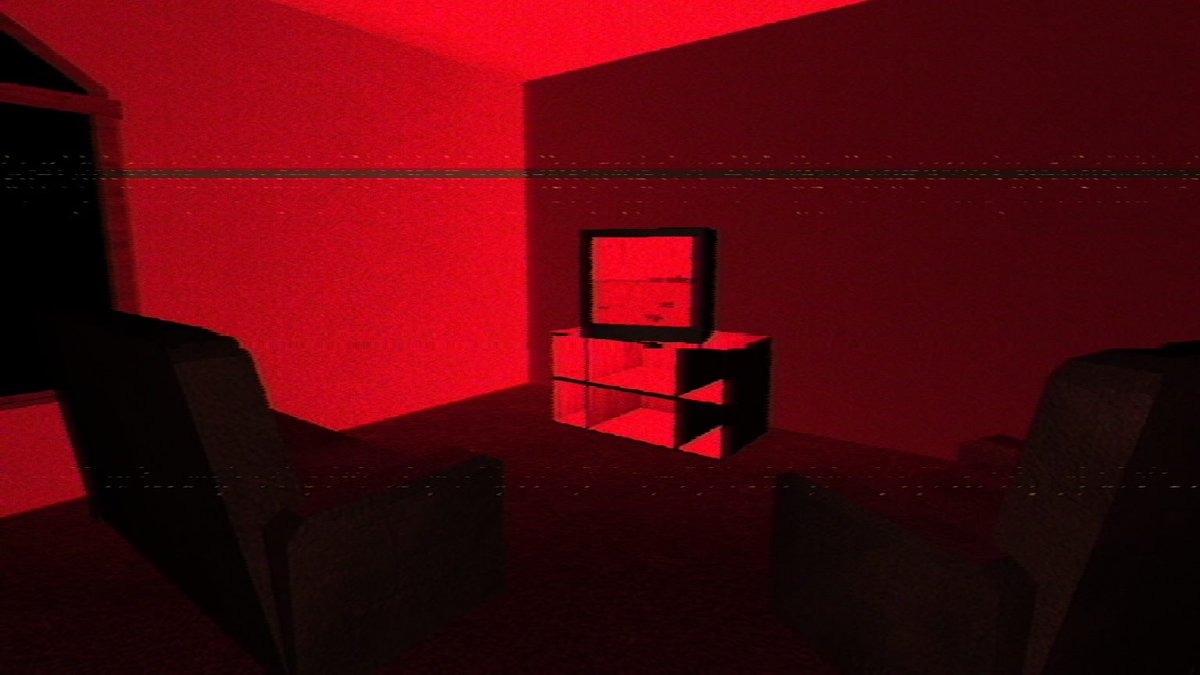

Every videogame has an important feature that immediately gives us a sense of what it’s about. It’s one we sometimes take for granted, and sometimes can’t help stopping to take a look at. It’s something that can comfort or terrify, interest or disgust, protect or harm, but it always serves a purpose in showing us the setting: the environment. A game’s environment can be the success or failure of its entire world.

But every environment needs to be populated, in one way or another. A videogame “enemy” can be considered a reasonably active obstacle that prevents the player from achieving the goals laid out by the game. The goal is survival? Here are some zombies who will try to kill you. Want to blow up a planet? Fight some of the beings who live there.

We see these intelligent obstacles as enemies only by their design, because they are given mesh bodies that move, react to and attack the player. But if we consider that spinning saw-blades, spring-loaded bear traps and a faulty rope bridge all react to the player, try to prevent them from reaching a goal and, in some cases, only harm them when activated, then they can be considered “enemies” too – at least in a functional sense. A great example of this is in one early section of Playdead’s Inside, where the little boy you are controlling has to avoid walking into a spotlight, or else he will be tased with prejudice. It is not completely clear where this taser comes from, so it is even harder to say whether it’s an enemy, a trap or both.

In platforming puzzle games, there are often sections like this. Sections where you have to traverse an area of a building or a ruin by avoiding traps and triggering switches. These are moving obstacles for you to navigate, which threaten you or, in some cases, help you progress. In that sense, the environment becomes your friend or foe.

A booby-trapped room is fighting against the player, just like a zombie alien from the future. If we consider that to be the case, then what about a non-booby-trapped room? Okay, so it’s no longer an obstacle; but if it contains objects that tell the player how to proceed, or describe events in the game’s narrative, then they are more than just locales – they are actively (this being the operative word) helping you progress, almost like non-player characters. In short, a helpful room full of objects is a participant in the story.

When we talk about our homes, we often use terms that ascribe some sort of personality to them. “This place has character.” “This house has good bones.” “This kitchen is so warm and friendly.” “This hallway is a bit frightening.” We personify buildings without realizing. A building that is completely square, concrete, grey, we think of as a lifeless, looming presence on a hill, threatening to come down on us. A whimsical cottage with a smoking chimney and a brightly colored door – we can almost imagine the kind soul who lives there, as if the house were a reflection of them, or more interestingly, they were a reflection of the house.

When walking through a house, or any sort of building, we get a sense of what it’s like to live there. The Fullbright Company’s Gone Home is a great example of this – the house is large, at times feeling yawning and endless, because it’s almost completely empty. Rooms haven’t been fully moved into, closets are clothes-less, packed-up crockery sits adjacent to the kitchen cabinets rather than in them. It’s a house that hasn’t been “peopled” yet. It exists liminally, not serving the purpose it was designed for. This immediately creates tension, especially in the night-time setting, with the ominous thunderstorm outside. Since Gone Home has no ghosts or ghouls hiding away in the rafters (though there are a few close encounters in the walls), it’s simply a story of the people who live there. There is a moment when you find a bathroom covered in blood, until you find a bottle of red hair dye, and realize that no, nobody died here, they just got overzealous trying to look punk.

But who is telling this story? Certainly not the inhabitants – they’re not there. Not the player, because you’re there to absorb the story, not describe it. The only thing left that could be telling the story, that could exist in the world of the game and encapsulate that world in a narrative sense, is the house itself.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue .

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!