Spain

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #137. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #137. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Globetrotting through media.

———

Welcome to World Tour, dig into your criadillas, listen out for the castanets and let’s get started!

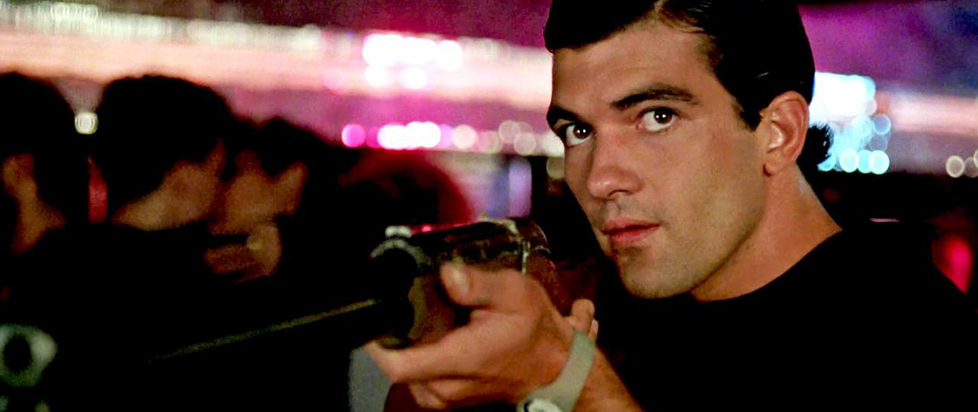

Law of Desire is a 1987 film by Pedro Almodóvar film about Pablo (Eusebio Poncela), a film director who’s disappointed with his young lover Juan (Miguel Molina) and starts an affair with another younger man Antonio (Antonio Banderas). As Antonio becomes aware of Juan, he takes increasingly drastic measures to assure that Pablo will never leave him.

From start to finish this film is fantastic. Almodóvar has a real talent for taking what is functionally a soap opera plotline, and making it work as an entrancing feature film. The exaggerated characters and their associated performances are probably the best part. Banderas is incredible as the film’s Evil Twink Antagonist, deftly manipulating and exaggerating both his perceived innocence and underlying malice. Carmen Maura is a powerhouse on the screen, always taking control of the scene and the rapport with her daughter Manuela Velasco is sweet and funny. Poncela does a great job of being deeply obnoxious but never unsympathetic.

What really makes this film stand out to me is the raw, unapologetic and deeply chaotic queerness. We casually open on a gay porn shoot. There’s no moralizing, no attempt to paint it as degrading, or even any major plot relevance. The scene is a fun and silly way to open the film, be introduced to one of the characters and establish what to expect from the rest of it. I think there’s a tendency in modern queer film to make every intimate scene feel like the Most Important Thing in the world and we don’t do that here. They happen throughout the film, in both foreground and background. Some are defining moments of fiery passion filled with intensity by Ángel Luis Fernández’s cinematography and others just aren’t – and that’s fine.

Beyond the bedroom, Law of Desire continues to unabashedly bathe in its transgressiveness. The protagonists use cocaine frequently and casually. They swear and shout in the street, they wear phenomenal outrageous outfits. One of my favorite moments in the film is where the central queer found family of Tina (Maura), Ada (Velsaco) and Pablo (Poncela) are walking home on a muggy summer night and see a man hosing down the street. Without even really thinking about it, Tina jumps into the stream of water and there’s a held moment of her really just enjoying herself in this impulsive and ridiculous act. This scene in particular speaks to the broader philosophy here in the film and of Almodóvar generally. Not everything is plot or character relevant, we can have these messy and silly character moments. Just like real life people can make weird or even bad decisions just because it feels good in the moment.

This freedom to embrace our “base” urges feels like something that is missing from modern queer film. There are lots of longing stares and almost-touches but where is the blood, sweat and spit? I do still love some of these films. For example, Carol is incredible, and Moonlight is easily one of my favorite films of all time and they both home in on that longing. However, that’s not the entirety of what queer experience is and can be.

The key thing that Almodóvar does here is that instead of asking, “why is this here?” like so many of the circular online arguments about “vice” in film go – he asks, “why not?” The lives of a significant number of queer people contain copious amounts of sex, drugs and alcohol – so why pull away from that reality?

This approach runs in parallel to that of filmmakers like Isaac Julien and the late Derek Jarman, whose frenetic work doesn’t feel trapped by any sort of presumed straight observer who will chastise them for being too immoral. In Jarman’s Jubilee the protagonists go around stealing, killing and causing chaos on the streets of their dystopian world. Looking for Langston leans into the poetic beauty of the Harlem Renaissance, but also the frenetic vibrancy of its queerness.

Now this isn’t to say that these men and their work isn’t without issues. In Jubilee, Jarman throws a lot of wild imagery at the screen and whilst most of it lands, there is definitely some grim stuff which doesn’t. Julien’s work isn’t always perfect in terms of working as a cohesive film. Also, Almodóvar has a strange way of presenting both trans women and sexual abuse that is never mean-spirited but at times feels a little off kilter. It’s also important to note that the people who have been able to make these irreverent films which have gotten any sort of attention have predominantly been cis gay men.

The imperfection is part and parcel of the experimentation though. A liberated queerness in film isn’t flawless or uncomplicated. It also doesn’t sit entirely in the rose-tinted past either. Bonde, a 2019 short film directed by Black non-binary Brazilian Aspah Luccas has this refreshing freedom from the need to be legible to straight people and instead embraces its flamboyance and ridiculousness. There’s also Isabel Sandoval, whose most recent films Lingua Franca (2020) and Shangri-La (2021) possess a powerful eroticism which is sorely lacking from a lot of modern cinema and very deliberately doing that from the perspective of a trans Filipina woman.

As we slowly get more queer characters and stories on mainstream screens, it feels like the respectability politic has become deeply entrenched in the psyche – and we often don’t notice. It’s easy to pretend that the kind of cultural conservatism which marginalizes those on the outskirts is contained within particular people. Maybe the Bible-bashing pastor, or your old and dying grandad, or a Republican senator. The evil is contained within their minds, their bodies, their institutions. Reality is never that simple. To paraphrase Foucault, the power that these oppressive forces have doesn’t just perform violence upon us, they also construct us in their image. Being well-intended, having radical politics, or even being queer doesn’t stop that. At every moment we have to push back against the programming of respectability politics into our minds.

In short, to maintain a truly radical and subversive energy, queer characters need to be allowed to be messy. We need queers who drink. Queers who do drugs. Queers who steal, Queers who lie. Queers who cheat. Queers who will kill to keep their lover loyal. Queers who want to burn everything down. They can’t co-opt the flames.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, podcaster and general procrastinator from London. You can find their ramblings @naijap-rince21 and their poetry @tayowrites.