A Tale of Two Godzillas

This is a reprint of the cover essay from Issue #37 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the cover essay from Issue #37 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

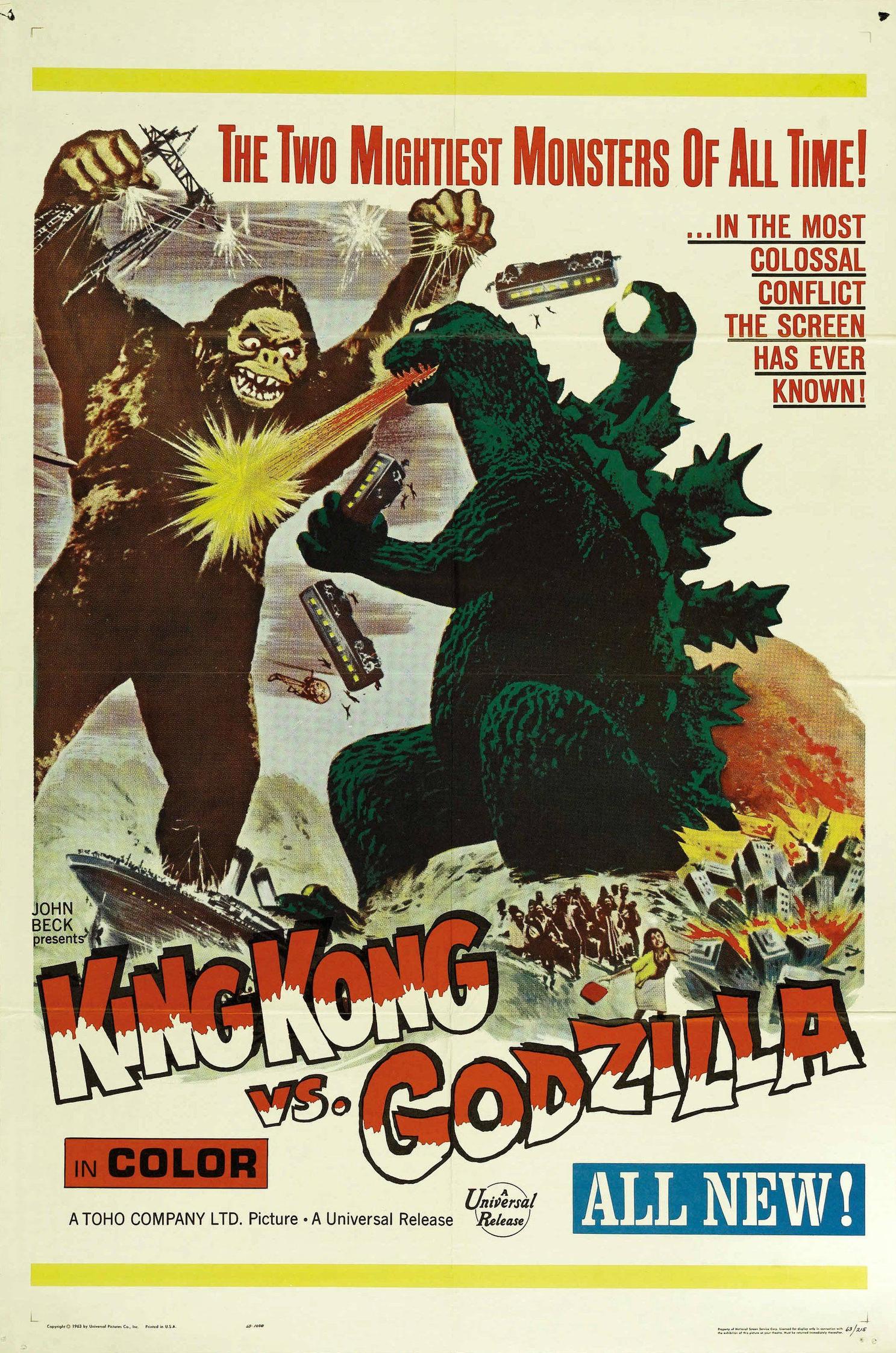

One of the longest enduring myths in cinema was how there were supposedly two distinct endings to 1962’s King Kong vs Godzilla: in the American release of the movie, King Kong was the kaiju that emerged victorious, while in the original Japanese cut of the movie, Godzilla came out on top. For decades, this falsehood was widely accepted, until the 1990s with the rise of home video and easier access to original Japanese media; in both versions of the movie, King Kong lives while Godzilla is lost to the ocean’s depths, presumably defeated. While it was a lie, there being two different endings made sense; Godzilla was thought of as Japan’s hometown hero, so why was he instead the antagonist on both sides of the Pacific?

Having appeared in over 30 movies across nearly seven decades, Godzilla’s been depicted in nearly every role imaginable for a giant movie monster. An analogy for nuclear weaponry and the misuse of its power, nature’s vengeance, defender of the earth, even the embodiment of vengeful souls killed during World War II. While the Showa era movies (1954 to 1975) saw him evolve from a vehicle of pure destruction to a kid-friendly, almost superhero-like role fighting more outright villainous monsters, the Heisei era (1984 to 1995) onwards to the present day has mostly seen the monster in all Japanese media as at best an antihero who still causes massive damage, while usually still being an antagonist of sorts that has to be dealt with by the film’s end. Given that Godzilla was originally a direct metaphor for the damage of nuclear bombings and tests, this antagonistic aspect enduring to this day isn’t surprising, but what’s truly odd is how in American depictions, Godzilla’s role has mostly been the exact opposite.

For as much shit the 1998 movie takes (and deserves), it is arguably the one American incarnation of the monster that keeps Godzilla as an antagonist. Sure, the monster isn’t complicated with no underlying, meaningful themes to speak of, but Zilla is still the obstacle that has to be overcome. The other two big pieces of American Godzilla media (the 2014 and 2019 movies), however, feature Big G as a straight up antihero; he destroys buildings, causes tsunamis and wipes out San Francisco and Boston, sure, but we’re meant to root for him as he saves us from far worse threats. This isn’t to say the character has fallen back on being a basic superhero (the 2014 movie has plenty of clear connections to real world disasters like Fukushima, Hurricane Katrina and the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami), but it’s striking to see the difference in how the character has been depicted between two countries.

For as much shit the 1998 movie takes (and deserves), it is arguably the one American incarnation of the monster that keeps Godzilla as an antagonist. Sure, the monster isn’t complicated with no underlying, meaningful themes to speak of, but Zilla is still the obstacle that has to be overcome. The other two big pieces of American Godzilla media (the 2014 and 2019 movies), however, feature Big G as a straight up antihero; he destroys buildings, causes tsunamis and wipes out San Francisco and Boston, sure, but we’re meant to root for him as he saves us from far worse threats. This isn’t to say the character has fallen back on being a basic superhero (the 2014 movie has plenty of clear connections to real world disasters like Fukushima, Hurricane Katrina and the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami), but it’s striking to see the difference in how the character has been depicted between two countries.

Godzilla’s more amicable depiction in American media isn’t completely surprising, due to a combination of wanting to make him more likable for mainstream audiences, how the US was the country that used nuclear weapons on Japan in the first place and how we’ve never truly had a firsthand reckoning with the existential threat of said weaponry. Meanwhile, Japan has continuously revisited the character due to nuclear mishaps, with Godzilla’s reintroduction in the 80s being a response to Three Mile Island, and 2016’s Shin Godzilla being a clear commentary on the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, and the subsequent crisis of the aforementioned Fukushima power plant. But it must be said that while the gulf between these two approaches is wildly different in tone and intent, neither is “incorrect”. The character has taken on a dozen different roles across dozens of continuities, and even King Kong has gone through a similar evolution of being a straightforward monster in the 1930s, while ending up as a far more sympathetic character in the 2000s and 2010s. No matter the creative team or the time he’s in, the one constant about the king of the monsters is that he’s never “just a monster.” There’s always something more to him than that.