Oddly Familiar

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #136. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #136. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Bucking the critical consensus.

———

The end of the Trump presidency has led to a good deal of media discussion around the “post-truth” phenomenon in politics – the idea that there once was something like a shared conception of reality that politicians and the public more or less agreed upon (and within which they had their debates) and that it now no longer exists. With the Trump administration’s sustained attacks on the legitimacy of the election helping to inspire the events on January 6, it looked like all those years of the administration habitually lying had finally created the kind of political rupture that couldn’t be ignored or undone. Having Trump out of office won’t do much to bring down the temperature in the US.

But the history of how this situation developed is more complicated than the claim that Trump represents a total break with precedent, or that his administration’s behavior is solely responsible for this political climate. Blatant dishonesty has always been a feature of US politics. With that acknowledged, it becomes easier to see the Trump administration as a dangerous evolution, rather than something entirely new.

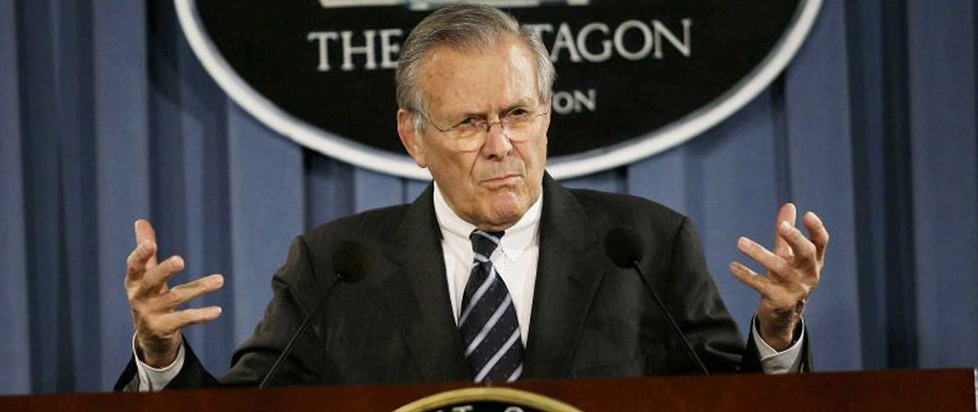

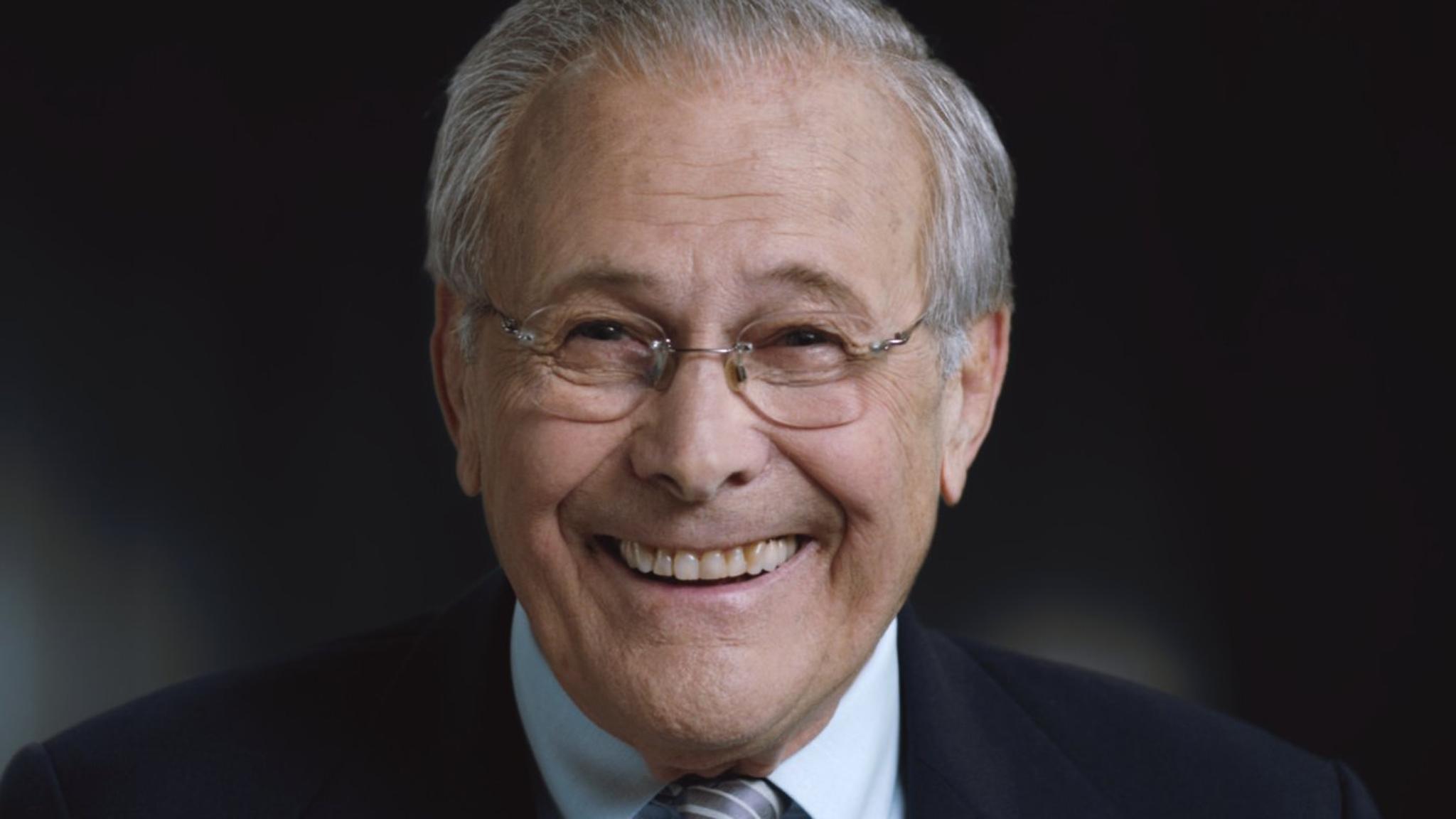

The Unknown Known, directed by Errol Morris and released in 2013, speaks to this without ever mentioning Trump, the Tea Party or any of the past decade’s other developments within the Republican Party. Instead, it looks just a little further back. Morris compiled his film from hours of interviews he conducted with Donald Rumsfeld about his life and career, focusing in particular on his tenure as Secretary of Defense under George W. Bush. In that office, Rumsfeld was instrumental in crafting the strategies and dishonest justifications for the US government’s warmongering, including the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Rumsfeld’s perspective on the Bush administration’s actions doesn’t seem to have changed much at all in the years between his exit and the interviews here. He doesn’t take any responsibility for lying to justify invading Iraq or for any of the consequences of that invasion. Instead, he just spends a lot of time denying, talking in circles or lying in new ways. Morris, then, resorts to weaving in newsreel footage from the Bush era to highlight – to the viewer, at least, as Rumsfeld is a lost cause – the extent to which Rumsfeld continues to deceive.

At one point, Morris tells Rumsfeld that some in the US public mistakenly believed that Saddam Hussein was involved with al-Qaeda and the attacks on 9/11; he cites a poll from 2003 in which nearly 70% of respondents said as much. Rumsfeld claims neither he nor anyone else in the Bush administration ever said anything to suggest that that was the case. Morris then cuts to a clip from a 2003 White House press conference the month before the US invaded Iraq where a reporter quotes Saddam as saying, “I would like to tell you, directly, we have no relationship with al-Qaeda.” Before the reporter can ask a question, Rumsfeld interjects, “And Abraham Lincoln was short.” He goes on to say that Saddam’s statement is a “case of the local liar coming up again and people repeating what he said and forgetting to say that he never – almost never, rarely – tells the truth.”

It’s pretty unlikely that Rumsfeld doesn’t recall any of the administration’s repeated attempts to connect Saddam to al-Qaeda (and 9/11 more specifically), but that’s the point. They lied then and continue to lie over a decade later because it helps get the desired results.

Today, The Unknown Known provides more evidence of the reality that the Trump administration’s deception – its “assault on truth,” as some called it – has deep roots. And by trying to distance the Trump administration from any sort of political precedent in the US, by suggesting that he was a total anomaly who somehow landed in the Oval Office, commentators overlook the ways that the US government has consistently denied and downplayed the horrifying impacts of its militarism and imperial ambitions since the country’s founding.

Rumsfeld differs from the Trump team in that he is (superficially, at least) more invested in establishing some sort of philosophical framework for what he does. He takes advantage of every opportunity he can to discuss his theories about what it means to truly know something, to ponder the kinds of calculations that must be made to make decisions at the highest levels of government, or to flip around someone’s argument to try and prove how personal perspectives bias everything. This created a more intriguing character for media observers to try and analyze both during and after his term (The Unknown Known itself is one example of that). Some found him to be an impressive figure, even as they claimed to disagree with his positions.

Of course, the end result was often the same as it was during Trump’s term: lies in service of brutality. The most noticeable difference was in presentation. And while it’s critical to identify those differences in presentation and their potential repercussions, it’s dangerous to discount all the ways in which Trump’s predecessors cleared the path for him.

Morris includes, for example, an extended excerpt from a White House press conference from mid-April 2003 – just a few weeks before Bush would declare “mission accomplished” – where Rumsfeld expresses indignation at the reporting on the war. The US was “liberating” Iraq, he says, using the administration’s notorious euphemism, and journalists were not appreciating that fact because they were too focused on the extraordinary violence of the invasion. This language is obviously insulting, but it accomplished what Rumsfeld wanted. By insisting it was the case, he helped set the terms for and perpetuate the debate around the US’ invasion of Iraq, despite there really being very little to debate about what was and remains an unmistakable atrocity. And Rumsfeld and company are just some of the more recent examples of this kind of behavior.

I don’t want to imply that nothing ever changes or that none of what’s going on is worth talking about. The developments of the past few years – the increase in far-right political violence, the escalation in reactionary and conspiratorial rhetoric, the rise in hate crimes, and more – are genuinely alarming, and dismissing this progression is irresponsible. But there’s also a risk in trying to isolate the Trump administration in history, rather than reckon with how it relates to – both builds upon and departs from – everything that came before. Without that kind of reckoning, there’s no way to address the fundamental issues that enabled the Trump campaign’s success in the first place. As Rumsfeld reminds us, we don’t have to look too far back to begin that research.

———

Adam Boffa is a writer and musician from New Jersey. You can follow him on Twitter @Ambinate.

———