RIP MF DOOM

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #135. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #135. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Selections of noteworthy hip hop.

———

It’s hard to know how to process the death of a celebrity. For the most part, I try and keep a strong distance, no matter how well known they are. “You didn’t personally know this person – it’s a parasocial relationship,” I tell myself. For me at least, that relief holds me through most celebrities’ deaths, but not this time. On the last day of 2020, MF DOOM’s family announced that he died at the end of October in London, giving one of the worst years ever a final fuck you.

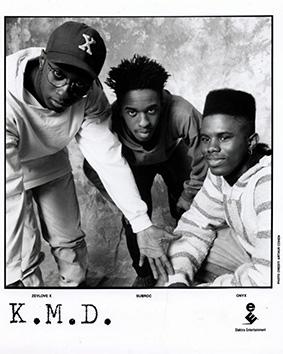

Often called your favorite rapper’s favorite rapper, Daniel Dumile had a storied career. From his auspicious beginnings with KMD in the 1990s to his commercial and critical success as Madvillain, Dumile survived the deepest of personal tragedies and the greatest of personal triumphs in his 49 years in this realm.

I wish I could say that I’ve known about MF DOOM since he was breaking through in the early ‘90s. I wish I was one of those elite few, following him from his career as an unknown artist in the New York underground, but I’m not. I’m not a rapper who spent everyday pouring over his lyrics, dying to replicate his style as grow with it. No . . . I’m just a fan. But having DOOM work his way into my life over the last decade and a half through my headphones, speaking eloquent truths and posing metaphysical questions that wrinkled my brain, I feel like his death hurts more than most.

I remember coming across DOOM’s work first on The Mouse and the Mask – his collab albums with Danger Mouse and Adult Swim, a year or two after it premiered. It was funny, audacious and, above all, lyrically brilliant. But even though I understood how good it was, I was still too deep in the 90s vibe to give it a second look. This seemed just kind of goofy, even if there were interesting tracks.

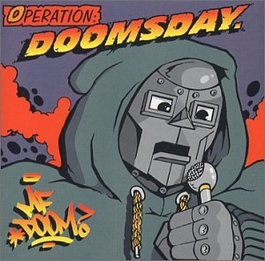

I knew DOOM was good, but I wasn’t aware of how good until a couple years later, when I picked up his first album as MF DOOM, Operation: Doomsday. From the first sample to the final beat, DOOM’s blend of comic book mythology, intricate rhyme schemes and psychedelic scratching and production hooked me. I suddenly needed to learn everything I could about DOOM, and in that blog-era before streaming music went global, the torrent underground was ripe with DOOM material to explore. Soon, I was diving deep into the mythology that he had built for himself over the course of two decades.

From his early work with KMD to his reappearance as an anonymous rapper wearing a broken Gladiator mask five years later, to his alternative personas that each took on different tones and different styles, I felt like his depths were endless. DOOM was funny, acerbic, witty, biting and genuinely brilliant. Above all, DOOM was best known for his internal tongue-twisting rhyme-schemes, dripping every verse with double and triple (and, if you believe Genius.com, quadruple) entendres.

From his early work with KMD to his reappearance as an anonymous rapper wearing a broken Gladiator mask five years later, to his alternative personas that each took on different tones and different styles, I felt like his depths were endless. DOOM was funny, acerbic, witty, biting and genuinely brilliant. Above all, DOOM was best known for his internal tongue-twisting rhyme-schemes, dripping every verse with double and triple (and, if you believe Genius.com, quadruple) entendres.

Although not political on the surface, Dumile continued the radical politics of KMD as MF DOOM, layering commentary throughout his lyrics, deeply embedding it within the metaphor of the eternal outsider. In fact, Dumile was an outsider himself. Although he came up in the heady underground of classic-NYC hip hop in the 80s and 90s, he was actually born in London to African immigrants. As the Obama administration cracked down on immigration, DOOM’s visa was caught up in the sweep and he was stranded in London, never to set foot in the US again –banished, like the supervillain he portrayed.

Fundamentally, he was able to achieve this level of depth due to his self-mythologizing. I don’t know if he has the most alternate personas in the history of hip hop (I feel like Kool Keith probably holds the crown on that front), but Dumile created whole worlds with his music. Yes, MF DOOM, the supervillain who loved children, was his most successful character, but all of his characters produced amazing music that circulated in the same realm, but with distinct personas. Viktor Vaughn, the narcissistic playboy, and King Gheedora, the alien monster here to destroy the world, populated DOOM’s comic universe, providing comedic relief and threats to the ultimate villain.

Fundamentally, he was able to achieve this level of depth due to his self-mythologizing. I don’t know if he has the most alternate personas in the history of hip hop (I feel like Kool Keith probably holds the crown on that front), but Dumile created whole worlds with his music. Yes, MF DOOM, the supervillain who loved children, was his most successful character, but all of his characters produced amazing music that circulated in the same realm, but with distinct personas. Viktor Vaughn, the narcissistic playboy, and King Gheedora, the alien monster here to destroy the world, populated DOOM’s comic universe, providing comedic relief and threats to the ultimate villain.

His production was just as amazing as his lyrical content, if not more so. Drawing on samples from old Fantastic Four cartoons, the Godzilla franchise and countless movies, TV shows and albums that I can’t even begin to list, DOOM’s production aesthetic is unparalleled. At once boom-bap oriented but futuristic, surreal but straightforward, as Metal Fingers, DOOM was able to broaden his influence beyond lyrical stylings and self-mythologizing. Instead, he became a lodestar for rappers; a self-produced, independent rapper who inhabited his own world and didn’t rely on anybody else to make his fortune.

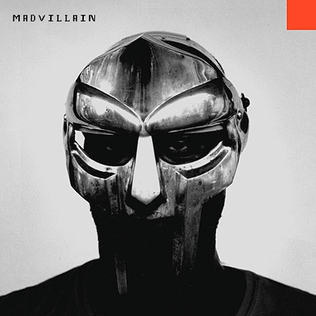

He also regularly partnered up with established artists and up-and comers to create unique, collaborative albums. The most well-known, and probably most well-regarded MF DOOM album, is his collaboration with Madlib, Madvillainy. Of all the albums that people praise DOOM for, Madvillainy probably reigns supreme as his masterpiece, but also the album I found the most inaccessible. Madlib’s jazzy production actively avoided radio-friendly tunes, eschewing hooks in favor of esoteric rhymes and blunt-infused psychedelia. Some of DOOM’s most iconic rhymes appear here, riding over snappy drums, funky bass, accordions, and obscure samples. Now an icon of independent hip hop and one of the best albums of all-time, Madvillainy will stand as DOOM’s lasting legacy to the hip hop world.

He also regularly partnered up with established artists and up-and comers to create unique, collaborative albums. The most well-known, and probably most well-regarded MF DOOM album, is his collaboration with Madlib, Madvillainy. Of all the albums that people praise DOOM for, Madvillainy probably reigns supreme as his masterpiece, but also the album I found the most inaccessible. Madlib’s jazzy production actively avoided radio-friendly tunes, eschewing hooks in favor of esoteric rhymes and blunt-infused psychedelia. Some of DOOM’s most iconic rhymes appear here, riding over snappy drums, funky bass, accordions, and obscure samples. Now an icon of independent hip hop and one of the best albums of all-time, Madvillainy will stand as DOOM’s lasting legacy to the hip hop world.

In the grand scheme of things, DOOM’s life ended as he lived it: in private. Often, his broken mask was a metaphor for hiding himself from the world, and hiding his own tragedy. In opposition to the glamorous image of mainstream hip hop at the end of the 1990s, DOOM hid from the bling, preferring anonymity to celebrity. It also felt like a mask for his emotions, shielding him from the 1993 death of his fellow-KMD member and brother, DJ Subroc and later the death of his son Malachi in 2017. Instead, his alternate personalities took over, papering his own tragic backstory with those from comics.

And maybe this is why his death feels somehow more personal than other celebrities — even more so than other rappers who also spit verses into my ears for years on end. Because DOOM spent his life behind a mask, adopting different personalities, emerging with different groups, he almost felt invincible. He would always appear in a different form, emerging from the shadows of another song, making a brief cameo in the background of another artist’s story. Even banished from his hometown, he would return triumphant. It still feels unreal that he isn’t lurking around a new corner, waiting to jump back into the fray. But maybe he’ll surprise us – he wouldn’t be the first rapper to release an album after death, and he certainly wouldn’t be the first supervillain to rise from the ashes.

RIP to MF DOOM Spotify Playlist

———

Noah Springer is a writer and editor based in Boston. You can follow him on Twitter @noahjspringer.