Adios: Farewell, Goodbye, Good Luck, So Long

This feature is reprinted from Unwinnable Monthly #134. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

This series of articles is made possible through the generous sponsorship of Epic’s Unreal Engine. While Epic puts us in touch with our subjects, they have no input or approval in the final story.

You can be forgiven if you see the short synopsis of Adios on Steam and think it is a horror game. “A pig farmer decides he no longer wants to dispose of bodies for the mob. What follows is a discussion between him and his would-be killer.” Considering the last time I visited a pig farm in fiction was in Hannibal, I understand why you’d brace for the worst.

“We talk a lot about ‘horror games,’ and I’ve always liked horror because it’s the only game genre where everyone on the team knows exactly what kind of emotions the team is going for,” says Doc Burford, director and writer of the game, and founder of Mischief, the studio developing it. “My design work is all about trying to capture emotion, so Paratopic was a horror game, and Adios is a melancholy game. Narratively, it’s a game about a pig farmer deciding he doesn’t want to dispose of bodies for the mob anymore; it’s a character study, a way of looking at a person and seeing who he is and how he reacts to things, fleshing him out both in the things the player can do and the way other people respond to him. Adios is a melancholy game.”

That idea of “melancholy” is penetrating. It isn’t a game about the mob, not really. Certainly not the way The Godfather or Goodfellas are, with characters discussing meatballs in the same breath as Sal potentially sleeping with the fishes. Nor is it a crime game. Well, except for the feeding people to pigs part.

“I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a mob story like this. I use the mob more as a means of creating tension; one man has to kill another man, but he doesn’t want to. The two of you are arguing about whether or not he has to, at least at first,” says Burford. “When I studied mob film back in school, a lot of what we watched really deals with the crimes and the complications that come from those crimes; Adios is a game where a father calls his neighbor and she starts rambling and he has to tell her how much she means to him without putting her life in danger. The mob functions as a complication, its role matters to the narrative, but it’s more of the plot motivator, rather than something we’re directly dealing with in the game. Adios has a lot more in common with, say, Martin Ritt’s movies like Hud or Norma Rae than Martin Scorsese’s, even though I wasn’t thinking about them as I was writing the game. I think they impacted my style, if that makes sense.”

In fact, more than other games or movies, Adios springs from a news story. “I read an article about a woman having a seizure and passing out on her farm, where she was eaten by her pigs, and after the initial sense of, ‘wow, that’s gruesome,’ I couldn’t help but find myself thinking about how sad it was that a person who’s loved and cared for their animals might end up finding those animals don’t really care for them at all. My reaction to reading this was just this powerful sense of heartbreak, and it was trying to untangle the melancholy feelings that came with it that helped me work out the game.”

* * *

Adios is Mischief’s debut game, but it has been a long road to get here. Way back when, Burford wanted to fly. “I was going to be a pilot before I became disabled, but after my doctors said I wouldn’t be able to fly anymore, I had to completely reevaluate my life.”

Burford combined a love of flight with videogames at an early age, modding Microsoft Flight Simulator, making new planes, messing with particle systems. Once being a pilot was off the table, game design seemed like a good alternative. “I went to school, but the department collapsed while I was there, so I didn’t really learn what I needed to,” he says. “I ended up in poverty, surviving off of food stamps while trying to make my way through college.”

Next up were film and journalism. Games got in the mix again, with Burford contributing to Kotaku, over the course of seven years, a series of articles about how games work. That led to a stint of consulting for game development, but that still wasn’t enough. “I still couldn’t afford to treat my disability and live, so I ended up losing my home. Since I was still wanting to make games, I came up with a really small project about a sort of road trip walking sim about chasing a series of video tapes, which ended up being called Paratopic.

“Paratopic was my attempt at addressing issues I saw with the walking sim, so where many of them were about off-screen narratives happening with no one around and little interactivity, I designed Paratopic around this idea of having lots of things to do, with the story you were engaging with also being the main story of the game; at the same time, it was really, really important for me to have the player interact with other characters, because I’ve played so many walking sims where you’re the only person around.”

Paratopic shipped in March of 2018 and went on to win the 2019 Independent Games Festival award for excellence in audio. Burford met new collaborators and was keen to take his ideas further, not just in design but in the structure of the workplace.

Burford founded Mischief with an eye towards the health of himself and his team. The studio puts supportive policies regarding health first. “I’ve crunched really bad on previous titles, and had people at various employers throughout my life go out of their way to make things worse because I’m disabled, like assigning me to locations with bad ventilation after receiving a doctor’s note saying that I needed to work in a place with good ventilation,” he says. “So I wanted to create a studio that’s super supportive of its team’s health and needs, because no one should have to go through what I’ve been through as a disabled person.”

Adios builds on Burford’s previous creative work, too, of course. Paratopic is in many ways Burford posing a question about walking simulators and narrative. Adios is about taking the answers learned through Paratopic further. “The goal here is trying to create a contiguous environment where you spend lots of time with another person, rather than just simple dialog trees with characters in fixed locations, and having lots of different verbs within that same space,” he says. “It’s very much a natural progression from what I came up with when I conceived Paratopic. My goal is, ultimately, to take the lessons I’m learning from this and the technology my partner Cameron [Ceschini, lead programmer and studio co-founder] and I are building here and ultimately build extremely dense, fully realized worlds with narrative experiences that do more than traditional games. To get there, I’ve got to make small games until I can afford to make big ones.”

* * *

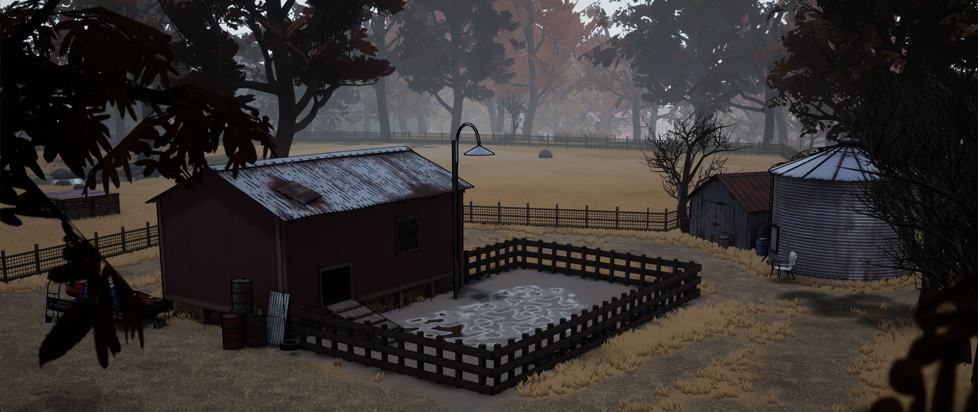

As much as Adios is about two people talking, the farm itself is also a looming character. Or, at the very least, an extension of the farmer’s character.

“I spent a lot of time thinking of the history of the space, when the farmer might have built additions to the house, when he first started disposing of bodies and how he used some of that money to rebuild the entire kitchen, which is why the kitchen furniture is all clearly part of a set, one of those yellow fridges from the late 70s,” says Burford. “Each room is a bit different; there’s something like 50 years of set dressing there, condensed into one space. I also tried to use it as a way of creating character, so as I was writing the game – that script’s all me – I thought about how the farmer was probably a bit of a pack rat and liked repurposing things, so there’s things like an old church pew out by the fire pit near the fishing pond. Instead of feeling like this sort of immaculately-designed AAA ‘everything in the game is super high detail,’ I went for recognizable variety that feels true to the farms I’ve been to throughout my life.”

The idea is to create a truly believable space. Lead artist Andrea Jörgensen has brought in real world geographical data from Kansas to breathe life into the space. Burford appreciates this attention to detail and specificity. And it gets at something larger about approach that Adios is reaching for. It goes back to Burford’s time studying film.

“American films are built for export – they’re made so people who don’t speak English can enjoy them just as much as everyone else – but the result is that there’s a kind of lack of authenticity; it’s not communicating the lived experiences of Americans,” says Burford. “I’ve never sat there and watched a movie and gone ‘Oh, wow, that’s me, I finally feel like I’ve been seen.’ Foreign films are different. When someone in Korea or Argentina makes a movie, that movie is always going to be far more about the culture it’s made in, often because these countries prioritize funding for movies specifically about their cultures. I’m used to being told Kansas doesn’t matter, it’s a flyover state, it isn’t real. When people compared Paratopic to Lynch, they were doing it because their exposure to the haunted strangeness of small towns in America is nothing beyond that one reference, while I was making an autobiographical game through the lens of horror. My own exposure to Lynch’s work was extremely minimal at the time; I ended up watching him because people kept comparing us.”

These details, this sort of accuracy is important, even if you can’t perceive them. Unnoticed, they contribute to the bigger tapestry of the game. “I remember reading this story about a filmmaker, whose name I’m forgetting right now, who was making movies in the 1950s or 60s with cameras that couldn’t pick up set detail very well,” he says. “Despite this, they had things like dust and dead flies on their set, and when someone asked the filmmaker why this was necessary, their response was like, ‘Well, you might not be able to see it, but you can feel it.’ Capturing the true sense of a space is so key to making the player feel like they’re there. So as we worked on the game, a big goal of mine was to make it feel like a truly authentic Kansas farmhouse from 1992.”

* * *

Which still leaves us with the burning question: what is Adios really, truly about? A farmer dealing with the consequences of his actions. A place evolved out of those actions. The details of a life filtered through a videogame. More? Less? Does it matter?

“There’s this moment in Stalker, one of my favorite movies, where the stalker says ‘I bring people here like me, desperate and tormented, and I can help them! I can help them, and it makes me so happy I want to cry.’ I know a lot of English 101 classes try to teach students that there can be more to fiction than just the plot, but I feel like a lot of people learn the wrong lesson and think every work of fiction must have some sort of actionable message it’s trying to convey. I’m not trying to do that, and you’ll find that a lot of the great artists, Le Guin, Tarkovsky, Lynch, Taro, all vehemently oppose this kind of message fiction. Stories aren’t argumentative essays; I’m not trying to argue a point and have the audience take something away from it. That’s something I do when I write, y’know, actually argumentative essays, which I’ve done a lot as a games critic.

“So, yes, I want you to take something away from this, but I’m not writing my stories like a first-year film student who’s just read Story and thinks every story has to have a theme that you can get in a single sentence. This is a game about existing within a space, closely observing and empathizing with another human being. He’s flawed, he’s messed up, some people are never going to forgive him, and it’s not clear whether or not he’s capable of forgiving himself. What I want for everyone who plays the game is for them to just let it wash over them, feel it, embrace it and, hopefully, if it works, then those people who are desperate and tormented and dealing with difficult things can play this game and the act of playing the game can help them through the difficult things they’re working through.”

* * *

Adios doesn’t have a firm release date, but Burford is aiming for sometime in the first quarter of 2021. It will be out on Xbox and Steam. You can watch the trailer here.