Sing It Out

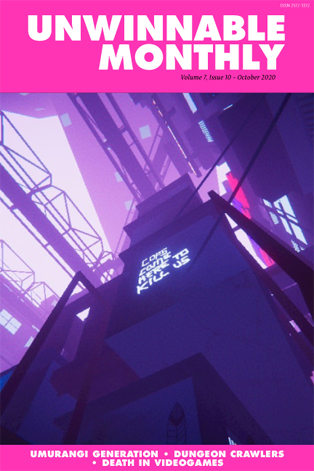

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #132. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #132. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Finding deeper meaning beneath the virtual surface.

———

Lovers Rock, one of the films in Steve McQueen’s brilliant new “Small Axe” anthology about the UK’s West Indian community from the 1960s through the 1980s, is full of a palpable and irresistible energy. Like Kid ‘n Play once did in the 1990s, the film follows the comings and goings of a raucous house party, beginning in late afternoon as the DJ’s set up their ceiling-high sound system and ending with the harsh rays of the new day’s sun. Like Kid ‘n Play’s House Party, it is boastfully, recklessly black. It is a celebration of the peaks, valleys and crescendos of black love and passion, perceptibly hemmed in by unfriendly and violent whiteness.

It is also, unquestionably, an immigrant film. A film out to capture the unique experience of not being from where you’re currently at, of desperately searching for any markers of home; in people, in music, in food, in eyes, in lips, in smells. Its title refers not just to that style of music that shakes the wooden beams of the dance floor and gives paramours cause to grasp at and pull each other so close that not one inch of air is left between them, but to the site of it all: the house itself, and its party. This site is a small island in a turbulent sea; safe harbor in treacherous waters. Beyond the ramparts of the old Victorian walk-up providing rickety shelter for the revelers, the enemy taunts and rudely stares, pale white and sallow faces under gelled hair, on the lookout for stragglers from the pack, for lost souls who’ve wandered a bit too far away from the protective spell of the music.

We watched Lovers Rock at a drive-in. It was my first time going to one, being from a city where few drive, and inexpensive, undeveloped real estate is a rarity. Thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, watching movies in the relatively safe bubble (or island, as it were) of a car has become the only way to mimic the theatrical experience. The anthem-sounding horns of Dennis Brown’s “Things in Life” and the snapping pace of Carl Douglass’ “Kung Fu Fighting” rumbled out of our car’s speakers, shaking the suspension and rattling the air vents. Inside the car, it warmed us, chilled as we had been by the nervous attendants trying to adhere to vague social distancing regulations as they collected our tickets. We bounced in time with the dancers, feeling the heat and the joy bleed through into our own anxious reality.

Afterwards, I kept coming back to the memory of spending time with my mother’s young nieces in Tunisia. Whenever I’d visit, and we would go out, they’d dress up; coating their faces in makeup and dashing their necks with perfume. It didn’t matter if we were headed to a nightclub or a sandwich shop, they’d always arrive at our front door decked out in their absolute finest. If we drove or took a cab somewhere, my cousins would turn the radio dial until it landed, inevitably, on a love song, often by some famous North African crooner. Greats like the Egyptian chanteuse, Oum Kalthoum, or the Tunisian tenor, Lotfi Bouchnak. These were voices I had only heard through my mother’s stereo, sourced from her cherished collection of tape cassettes. My cousins would always sing along, matching every word, perfectly in tune with the music.

I remember feeling slightly jealous of the easy joy they could find in these moments. Their casual fluency in this musical language was one I could not share in, unversed as I was in the spoken language to begin with. Growing up in America, I rarely found similar camaraderie through Western music. My tastes were confused and uncertain. I was always late to the moment, frantically trying to keep up, unsure of whether I liked the music or if it was just a tool I could use to fit in.

During a scene in Lovers Rock in which Janet Kay’s “Silly Games” is placed on the turntable, the crowded dance floor vibrates in instant recognition. Groups of friends and paired-off couples dash in from off-screen rooms and hallways. They put out their cigarettes in the backyard, put down their plates of curry goat, and beat it rapidly onto the dance floor. Once the song properly gets underway, they sing and scream along to the lyrics, voiced as many, sounding as one. “No time to play your silly games. Silly ga-ames!” At the crescendo, the DJ cuts off the sound and lets the crowd set the beat and sing the words. No one is off, no one forgets a line, this anthem is ichor in their veins, inscribed upon their very bones.

In this way, music is a touchstone, a unifier, a reminder of who you are and who your people is. Outside of the boundaries of the party, it’s all wrong, all turned upside down. The music fades and no one is sure of how to act; how loud to be, what they can own, where they can stand, who they can be seen with. But huddled together in that tiny room, shouting along to the chorus until their throats go sore, these men and women experience no doubts, “no fear” as Nina Simone once described the sensation of love. It’s a powerful and moving display, a testament to the power of culture, of finding family and home in an alien place.

When I listen to my cousins sing to each other in Arabic, I can hear hints of this. But it’s like listening to someone speak to you through water, or through the static that lives between radio bands. I was born to an expat, an exile, so my own touchstones are second-handed from hers. My sense of community is patchwork, not anchored to anything but spread thin through the endless adaptation required for traveling between disparate social circles. The trade is a life far more privileged and comfortable than the one my Tunisian cousins have. In that way, my jealousy is unfair, misguided. I want something I do not really want. I want the one thing that they have, because it reminds me of what I am missing.

In the final post-party, early dawn moments of Lovers Rock, two newly-minted lovers, Martha and Franklin ride on a shared bike through the sleeping neighborhoods that lie between the island of the house party and the spaces where they spend the rest of their lives. In the garage where Franklin works, they embrace before being rudely interrupted by Franklin’s white manager, who attempts to intimidate Franklin, drawing power from the whiteness lurking within his diminutive frame. Driven from their safe bastions, they reluctantly part ways, and Martha sneaks back into her parent’s house. The film closes on her hastily snuck back into bed, playing the part of innocent church girl we gleefully recognize as false, and breaking into a broad cheek-spanning grin. Though the party’s music can no longer be heard, its echoes and its power reverberates through this moment, no white man can get her down, slings and arrows bounce harmlessly off the barriers the night has erected.

Perhaps it’s that shield that I miss, that protection grown from shared survival. Here, I survive mostly alone, to music that isn’t really my own, among others who are generally just as unmoored. The joy inherent to Lovers Rock, the joy of my cousins’ joyful chorus, is getting to pretend for a time that I too could wrap myself in music and feel invincible, feel the solidity of being moored to stone sunk down through miles of sea to the ancient bedrock below.

———

Yussef Cole is a writer and visual artist from the Bronx, NY. His specialty is graphic design for television but he also enjoys thinking and writing about games.