“To Steady the Box”

In Jack Gilbert’s poem “Michiko Dead”, the speaker struggles to carry a box that he can never put down. The title is the clearest definition of the box as we’re gonna get, as the poem itself is pure metaphor. There are no lines explicitly describing the loss of a loved one, but we understand what the box is:

He manages like somebody carrying a box

that is too heavy, first with his arms

underneath. When their strength gives out,

he moves the hands forward, hooking them

on the corners, pulling the weight against

his chest.

It’s grief, memories of all stripes that end a painful aftershock after loss that one can never be unburdened from. To call it a burden feels extreme, though Gilbert’s poem is resigned to describe it as such:

… He moves his thumbs slightly

when the fingers begin to tire, and it makes

different muscles take over. Afterward,

he carries it on his shoulder, until the blood

drains out of the arm that is stretched up

to steady the box and the arm goes numb.

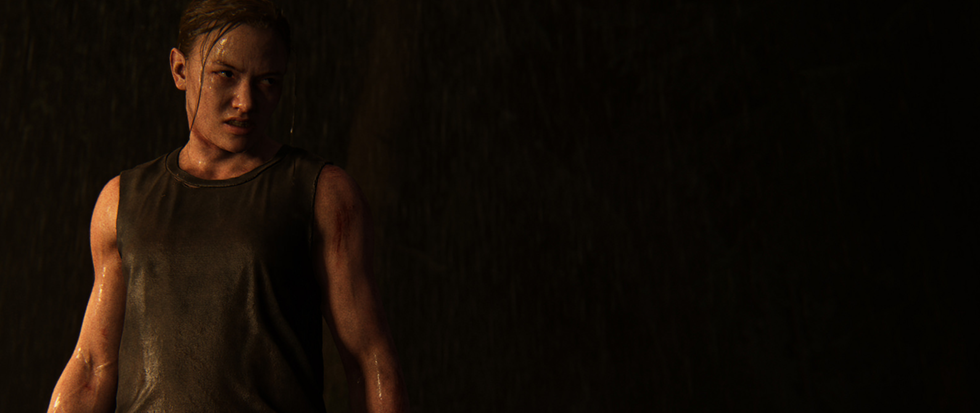

The Last of Us: Part II is a videogame about many things, one that succeeds in a fair shake of its lofty aspirations while stumbling on occasion, as well as egregiously failing its Black characters (as elegantly described for this site by Phillip Russell, over at Bullet Points with work from Yussef Cole and Cameron Kunzelman, and elsewhere). It’s imperfect, overlong at nearly twice the playtime of its predecessor, an astounding technical achievement marred by the inhumane crunch of development required to push out so far so fast, and it consumed my thoughts for more than a few nights while playing and even more after finishing it. And though director and co-writer Neil Druckmann has said that this sequel is a tale of revenge, to me it’s a story about grief and the false sense of strength that our culture ascribes to solitary stoicism.

The world of The Last of Us is defined by violence. The initial fifteen minutes of the first game put Joel’s daughter Sarah in the fridge as a way to define him throughout the rest of his journey in the fungal apocalypse. Despite the broken watch that only the player ironically recognizes throughout, Joel doesn’t speak of his daughter, hauling the box of his grief until his fingers throb, refusing to shift the weight as an act of silence. In his role as a father figure, Joel teaches this survival tactic to Ellie, and there’s no doubt that their actions are attempts at managing trauma in a hellish world that requires them to regularly destroy human and humanoid life. Everyone here is straining to carry the box that perseverance has left them with.

This refusal to speak on one’s feelings of grief sets the tone for nearly the remainder of Joel’s life, and the entirety of Abby and Ellie’s existence in these games. We are meant as players to try and understand the ouroboros of revenge, the two graves dug, the nation of the blind, as we follow Ellie’s self-destructive rampage to the breathless climax and then do the same for Abby, Joel’s killer. Abby carries her own box, the death of her father at Joel’s hands, a nameless doctor in the first game. Here he is given life after the fact of his death, in Abby’s playable memories.

Throughout my experience with both main characters I was wracked with conflicting desires — the experience of the game is such that I absolutely loved crawling through the grass to pick off infected, or to do my best to skirt around the human enemies until they inevitably caught up to me. Even then I rarely felt compelled to scum my way back to a better performance, instead caught up in the tension and drama of the moment and often led to a satisfying conclusion to even the most heinously botched stealth job or firefight. Though often satisfying in play, The Last of Us: Part II can’t help but remain well-stocked with videogame bullshit of course, off-path trinket collecting (as mellifluously defined in Tim Rogers’s video review of Final Fantasy VII: Remake) and callous player-condemning quick-time events being the most flagrant moments that would eject me from my other primary desire in this game, participating in the narrative.

Ellie and Abby grow in many ways, but the source of all narrative drama is a lack of forthright communication, creating a false binary. We are meant to consider that this ability to compress their feelings into a box and hoist it themselves until their arms go numb is a kind of strength. Abby is the first to diverge from this path, but she comes from a privileged position of having exacted her revenge. Of course, the false peace of her vengeance still prevents her from meaningfully reaching out to her complicated ex Owen, or truly connecting with her group of friends, and has sealed their violent fates by conscripting them into the gruesome killing of Joel. Even my brief joy at seeing Tommy still breathing quickly fades as it’s made clear that he remains haunted, emotionally and physically broken, clinging to his box of grief as a kind of addiction to avenging his brother (similar to how Blake Hester so eloquently puts it in his final column for Unwinnable) . Tommy callously and selfishly demands that Ellie do the same, and she acquiesces.

All of this is predictable, and a failure of imagination. Not just on Druckmann’s behalf (especially as the story was co-written with Halley Gross) and also not to be confused with a lack of creativity, as there is much grace in the art direction, soundtrack and even the brutal gameplay. It’s just that the true stakeholders in this story, Sony and the boards of directors and shareholders and creative decision makers have no interest in challenging entrenched notions of humanity’s innate desire for violence, particularly through revenge, beyond the capacity for dividends. Though we the players are meant to gasp every time we learn that a Seraphite or WLF soldier we garroted has a name or that their fellow soldiers might have actually known and cared for them, Ellie and Abby show no such recognition. They and we rack up body counts in the near hundreds, bowing down to what we are told we want as players, to exact violence, despite books and studies showing that friendliness and community likely played a much larger role in the advancement of human society than the capacity to shed the blood of competitors.

The Last of Us: Part II was created to generate profit, and publishers and studios feel that players will only spend high dollars on games that enact violence. This is the lack of imagination, that this is the only way Ellie and Abby’s stories could have gone because it’s what the players demanded. But what if Ellie actually communicated with Dina, or with Abby. The grief she feels throughout the game is the chance that she and Joel had, as we are shown in the end, to repair their relationship and overcome the isolation of stoicism. I don’t know how Naughty Dog might have created such a title, but at this stage of videogame evolution in technology and systems, perhaps such an effort might be the real leap forward in the medium.

We are left with Ellie walking away from the guitar, her fingers shattered (though as Reid McCarter points out, this needn’t be the end of her strumming days), and possibly from her torment over the death of Joel. But I like to think that, in sparing Abby and Lev, Ellie wasn’t abandoning her memories of Joel but learning to finally readjust her box of grief, to incorporate another method of managing it:

… But now

the man can hold underneath again, so that

he can go on without ever putting the box down.

Just as we find Abby’s letters to the ghost of Owen, I am hoping that Ellie can continue to find new ways to carry this box, the heavy grief of losing Joel, but also the joy in his memory. If only her creators had the capacity to imagine a videogame where she could talk to Dina, Tommy, or even Abby, in order to find new ways to shift that weight, without ever putting it down, without hours of visceral headshots masquerading as strength.

// Levi Rubeck is a critic and poet currently living in the Boston area. Check his links at levirubeck.com