England

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #130. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #130. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Globetrotting through media.

———

Welcome to World Tour! This is my column where I (metaphorically) travel the world and write about a couple of pieces of media from a different country every time. So fasten your seatbelts and brace yourselves for lots of terrible travel puns. For the first column, we’re starting on (my) home turf with England.

Bait isn’t really the first film you would associate with me. If you’ve followed any of my writing or any of my ramblings on Twitter, you probably wouldn’t expect me to be waxing lyrical about a black and white film following a culture clash between a Cornish village and some Londoners on holiday. And to be fair, I wouldn’t either! I watched this film on a whim and was blown away by it.

The first thing that hits you about Bait is that it’s shot on a vintage camera. More specifically, it’s a 16mm camera using monochrome Kodak stock. This could easily be a gimmick gunning for awards, but instead, it’s integral to the film. The speckles of white, the fluctuating shades of grey and the slightly jarring dubbed lines all give an unsettling and almost supernatural atmosphere. Mark Jenkin adds to this in his cinematography and editing, manipulating chronology with abrupt cuts to tiny specific moments in later scenes that foreshadow what’s to come. There’s a constant sense of dread that almost makes you feel like this film is haunted.

Whilet there is lots more that I could say about the phenomenal filmmaking and performances, it’s this sense of haunting, and how it ties in with the broader themes around gentrification slowly choking this village, that I’ll be focusing on. There are real parallels that could be made with some of Lovecraft’s work, much like in The Shadow over Innsmouth, there is a slow and steady invasion by an external force which seeks to destroy a place and supplant its way of life. You see this through symbols and the way they shift. A Range Rover replaces a beaten up pickup truck and is repeatedly used as a symbol of the entry of the upper-middle-class. A crab becomes a symbol of prosperity, creating the tensest sequence in the film. Except, unlike Lovecraft, this invasion and the oncoming apocalypse isn’t racist paranoia about miscegenation. Instead, the Lovecraftian feeling reflects the reality of how an (often white) well-off class seeks to monetize the abstract idea of a place, whilst hollowing it out and never engaging with the lives of the people who live there.

While Bait’s cast only consists of white people, it feels like there’s silent solidarity with racialized groups who often suffer at the hands of gentrification (especially in cities). This is one of the few pieces of media I’ve seen that so sharply portrays the cannibalistic and classed nature of English white nationalism. Though the Cornish people are white and reside in England, throughout history they’ve fought to maintain their own identity, including their own language that is used in parts of the film. At every stage in the film, they feel fully realized and unapologetically of their own culture – with Cornish actors playing those roles. A more popularly known parallel to this distinction is most succinctly pointed out by Jourdain Searles on the Bad Romance podcast, where she talks about how there’s a difference between the specific white cultures of the films of a director like Scorcese and the homogeneous whiteness present in most Hollywood films (which doesn’t excuse Scorcese’s record on race, but complicates it). The nature of English white nationalism requires homogeneity and a subscription to particular national myths around identity, so everything outside of that singular English identity must be consumed/co-opted – including cultures containing white people. Bait captures how through capitalism, Whiteness/Englishness (as a system of domination rather than an individual trait) cannibalizes its aberrant members to create a falsified image of unity and purity that facilitates the slow descent into a not-quite apocalypse of holiday homes and Airbnbs.

There is a bitter irony here – that this film understandably doesn’t get to. This self-inflicted decimation fuels an English white nationalism which blames the Other (often Muslims/racialized populations/Eastern Europeans) for the cultural void left by the same nationalism they uphold. So the remnants of actual traditional English cultures bleed out whilst their self-proclaimed knights daydream of halcyon days bathed in red and white.

* * *

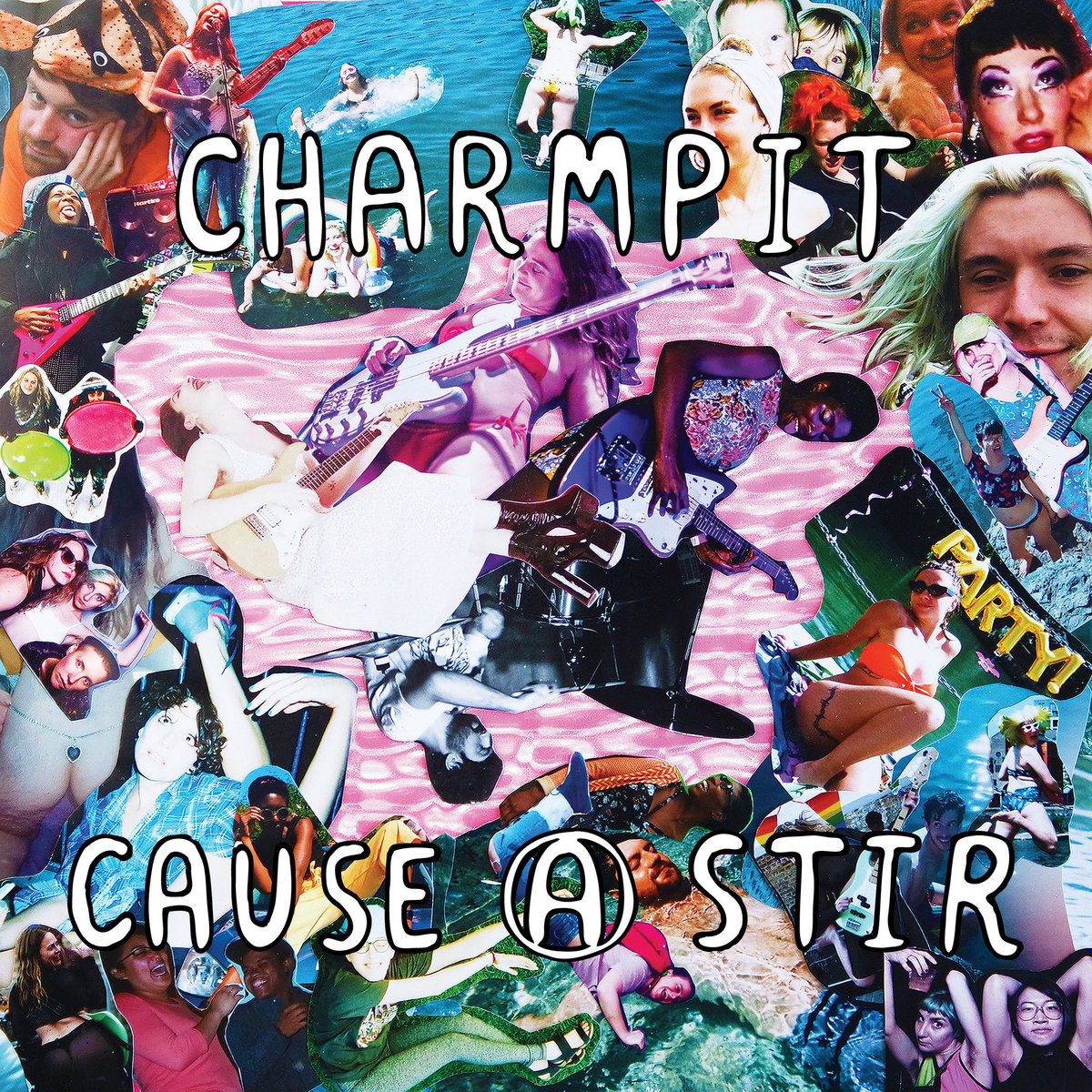

On the opposite end on the spectrum we have Charmpit’s recent-ish album Cause a Stir. Charmpit is a London-based band of self-described “PUNKstarPOP anarcho-cuties.” Their whole aesthetic is reminiscent of Josie and the Pussycats and riot grrrls, but brings that into the present day with a political edge.

On the opposite end on the spectrum we have Charmpit’s recent-ish album Cause a Stir. Charmpit is a London-based band of self-described “PUNKstarPOP anarcho-cuties.” Their whole aesthetic is reminiscent of Josie and the Pussycats and riot grrrls, but brings that into the present day with a political edge.

Their album is basically “good vibes” as a concept distilled into thirty minutes of music. I mean, what other band is putting out a cute song about a mall in 2020? No song overstays its welcome and you’ve got endless replay value, with bop after bop after bop, all of which are basically guaranteed to lift your mood. We are surrounded by “kindcore” pieces of media, whether that’s in games like Ooblets, or the endless infographics we see which talk about self-care in the abstract but skirt around material and structural difficulties. I think it’s rare to find something where the sweetness doesn’t feel like a disingenuous affect but actually seems to come from an earnest place of caring about other people. Cause a Stir is one of those rare cases.

Interwoven with the fun and the silliness is a lot of leftist/anarchist politics. Rather than feeling cynical, haughty or detached, their politics link in with the feeling of the music as they sing about “communist confetti.” It’s not like they’re reading Bakunin, but instead, they feel like the soundtrack to what a queer anarchist utopia would sound like. What they capture perfectly here is that while love and joy are universal, they aren’t apolitical. Creating joy and love that goes beyond the superficial sources which capitalism can commodify is more than just a broad idea or notion, it’s something to be specifically acted on. This is an album which is a perfect companion piece with Dirty Computer and Joy as an Act of Resistance, two favorites of mine which both understand the power and politic of connection and love in the face of a system which seeks to isolate you. It’s all the more powerful coming from a group of queer femmes with an infectious optimism which makes you feel like despite everything – the world could be better.

Interwoven with the fun and the silliness is a lot of leftist/anarchist politics. Rather than feeling cynical, haughty or detached, their politics link in with the feeling of the music as they sing about “communist confetti.” It’s not like they’re reading Bakunin, but instead, they feel like the soundtrack to what a queer anarchist utopia would sound like. What they capture perfectly here is that while love and joy are universal, they aren’t apolitical. Creating joy and love that goes beyond the superficial sources which capitalism can commodify is more than just a broad idea or notion, it’s something to be specifically acted on. This is an album which is a perfect companion piece with Dirty Computer and Joy as an Act of Resistance, two favorites of mine which both understand the power and politic of connection and love in the face of a system which seeks to isolate you. It’s all the more powerful coming from a group of queer femmes with an infectious optimism which makes you feel like despite everything – the world could be better.

That’s it from me this month. I’m off to pack my bags and cook my Jollof rice fro next month. So I’ll leave you with some words from the Charmpit song “Princess Video” for some words we could probably all use right now:

We’re gonna make it after all,

We’re gonna make it after all,

We’re gonna make it after all!

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, podcaster and general procrastinator from London. You can find their ramblings @naijap-rince21 and their poetry @tayowrites.