Digital Fuckery: The Monetization of WebToons

As I write this article, my phone is next to me, open to the webtoon reading app Tappytoon. It’s playing ads constantly. Every thirty seconds I reach over and close an ad, starting up a new one. I’m testing a theory I have that watching these ads will never give me more than 10 points, one of the two primary currencies in Tappytoon, despite the implication of the UI that shows a plus sign next to the 10, an implication that just once I may roll the dice and get slightly more points than a measly 10. Tappytoon will only let me do this 30 times in an hour.

That’s probably for the best.

WebToons are a unique construct of the digital age; digital manhwa intended to be read on smartphones, they’re not quite webcomics and not quite graphic novels. Their strange page shape means they’re less likely to be adapted into physical form (though you can find some print versions of popular WebToons like King’s Maker) and their online nature also lends itself to more prurient content. In many ways their unique digital platform also lends incredibly well to microtransactions, and it’s interesting to see the different ways that different applications and websites have chosen to monetize their content.

WebToons operate in a sense similar to platform exclusivity. Want to read the aforementioned King’s Maker? You’re only going to find it on Lezhin. Well, now that you’re on Lezhin and you’ve bought into their currency model, that’s fine, you’ll be able to read the sequel to King’s Maker there, right? Well, not exactly because King’s Maker: Triple Crown is actually on Tappytoon. If you want to read the official translation of the manhua companion to the extremely popular Chinese television show the Untamed, The Master of Diabolism however, well it’s not on either of those applications. It’s actually only on WeComics.

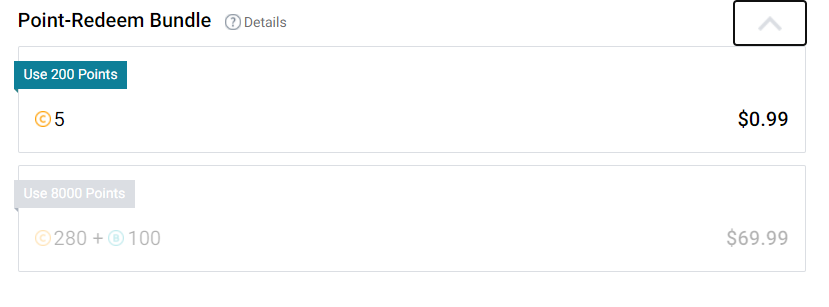

Every application has its own economy structured around a minimum of two separate currencies. Lezhin is interesting in that there are three currencies (Coins, Bonus Coins, and Points). It’s actually a pretty standard mobile microtransaction model, just settled around reading rather than around playing another round of a Match 3 game. If you’ve never played a mobile game in your life, the way currency systems like this work is simple: there is a currency you pay for and one you don’t. For example, let’s take WeComics and their two primary currencies, coins and shells.

In WeComics, shells are the free currency. You get them one of two ways. By logging in every day you get a regular bonus that increases for up to seven days before resetting (netting from 100-500 shells), and you also can watch a randomized amount of 1-5 ads per day for 200 shells per ad. Which sounds like a lot of shells. Except that shells don’t go as far in the economy of WeComics.

This is the bottom of a single chapter for a WebToon, which can usually run between 38-100+ chapters. They’re designed to be highly episodic and serialized content with plenty of cliffhangers to grab you at the end of every chapter so you just have to see what’s going to happen next. They were going to kiss at the end of the chapter…right? Are they going to at the beginning of the next or will it just be another fake out? Better drop that 150 shells just to be sure. Especially since your shells can expire after a certain, relatively short, amount of time leaving you with this sensation of false hurry.

Coins are the currency you pay for. WeComics conversion rate for their “coins” is actually fairly straightforward to real currency: it’s about one cent per coin. $9.99 will get you 999 coins. But the only way you really get them is through purchasing them.

Regularly you’ll see comments at the end of chapters that show despairing fans saying “OH NO I’M OUT OF SHELLS” or that beg the author, in vain, to turn the comic to free or to shells only so that they can read it faster.

There is a strategy going on here, even if I couldn’t tell you exactly what it is, because my intention when I came to the WeComics app was only to read Master of Diabolism and somehow I currently have 12 open and ongoing Webtoons that I’m following, with regular upload schedules throughout the week. Some of them (I’m looking at you Dragon Boy’s Love Affairs) were mostly started so that I wouldn’t feel guilty about wasted shells that were about to expire, instead choosing to take a chance on a read that I may otherwise not because hey, I wasn’t going to spend the shells anyway. Ninety-eight chapters later, I feel grumpy about this.

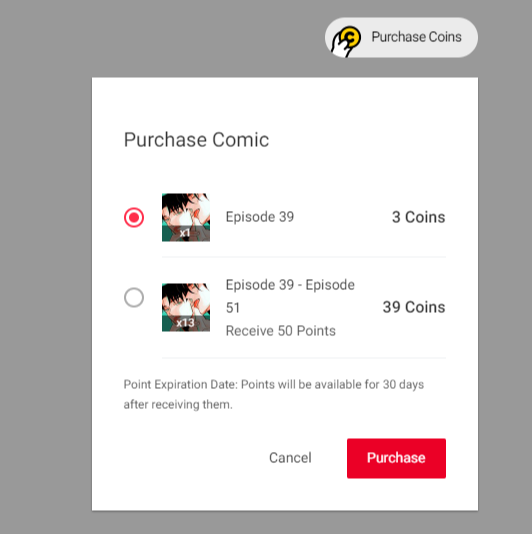

Some of the other applications for WebToons have a slightly more gambling feel to them. Lezhin feels almost like a casino with how in the dark you feel about the amount of currency you have. In a casino there are no windows so you can’t see the sun and you can never tell when the sun is set; you never know when you’ve spent too long, when your time there should be done and you should’ve left hours ago, already long broke. In the WeComics application, when you are prompted to spend your shells or coins, it tells you how much you have of both. The text is small, and to my slowly degenerating eyes, hard to read. But it’s there. With Lezhin, it’s not even there. They just ask you if you want to purchase the single chapter or the rest of the available chapters.

For context, when I took this screenshot I had 27 coins in my Lezhin wallet. If I had attempted the full purchase it would’ve taken me immediately to the purchase page to buy more coins. I have ended there several times, stumbling blindly into the sun and realizing that I had been in the dark for far too long.

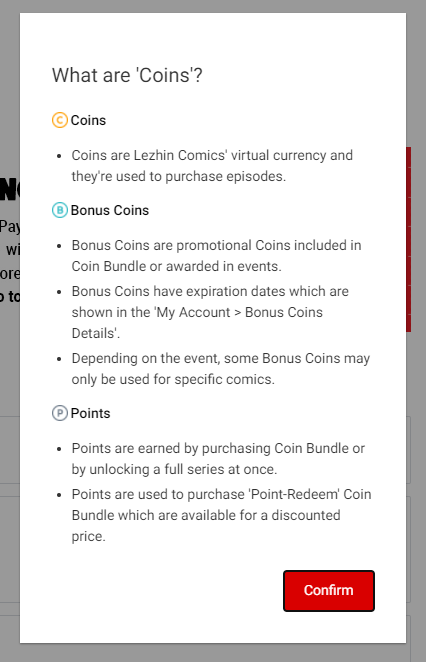

Lezhin has three currency systems, which they actually explain, probably out of necessity. Coins are their primary currency and the one that you pay for. Points are their free currency. In Lezhin’s case, you get them as bonuses during purchases and through daily logins. Bonus coins are where things get a little confusing, but don’t worry we’ll circle back to the extra confusing thing of how you actually spend points, which is probably the weirdest aspect of Lezhin’s currency system. Bonus coins are an additional currency that arrives in your inbox for specialty WebToons, usually promotional ones. They function similarly to coins, except they can only be used on specific comics (usually) and they have expiration dates.

Circling back to those points. Usually in a mobile microtransaction currency system in an application, you have one primary currency that has more powerful buying power and a free currency that has a weaker buying power (the shells vs the coins in WeComics). In Lezhin’s case, it’s actually a bit weirder.

This is the Point-Redeem bundle:

You can’t buy coins with points, not entirely. But you can slightly augment your actual money with points for a marginal discount on coins. How marginal? Well, 20 coins is normally $4.99 so if you bought 20 coins at $.99 a piece you would spend $3.96. You would save a dollar. Lezhin chapters run about three coins, so you would get 1 free chapter. The math on the blurred out deal is a bit harder to parse since there is no clear way to get there mathematically from the original full price coins. But they have a coin bundle for $49.99 for 220 coins, then you take 3 of those 20 coins/$4.99 bundles and you come out to $64.96 which is actually $5.03 cheaper, making it seem mathematically and financially like a better deal and it doesn’t involve spending 8000 points. Sure you don’t get the 100 Bonus coins, but those expire and aren’t real currency.

I honestly don’t understand the Point-Redeem bundles.

These systems are designed to keep the reader in place, to keep them reading as long as possible and on the same sites, spending currency in the same place. They incentivize reading habits that encourage you to pick up other WebToons in their oeuvre. Bonus Coins are why I found the phenomenal Love or Hate on Lezhin’s website, through an event they were running. They’re an effective strategy, which is why they keep utilizing them.

Tappytoon is on the other side of the effective coin, as their strategizing has come off as instead cheaper? They follow the standard model of two currencies: points and tokens. Tokens are the paid currency and points the free currency, and as we started this very long deep dive into monetization strategies of WebToon apps, I had the Tappytoon app open on my lap hitting that tiny “x” in the upper right hand corner every 30 seconds or so. I never made more than 10 points per ad, and eventually ran out of my 30 potential ads in an hour.

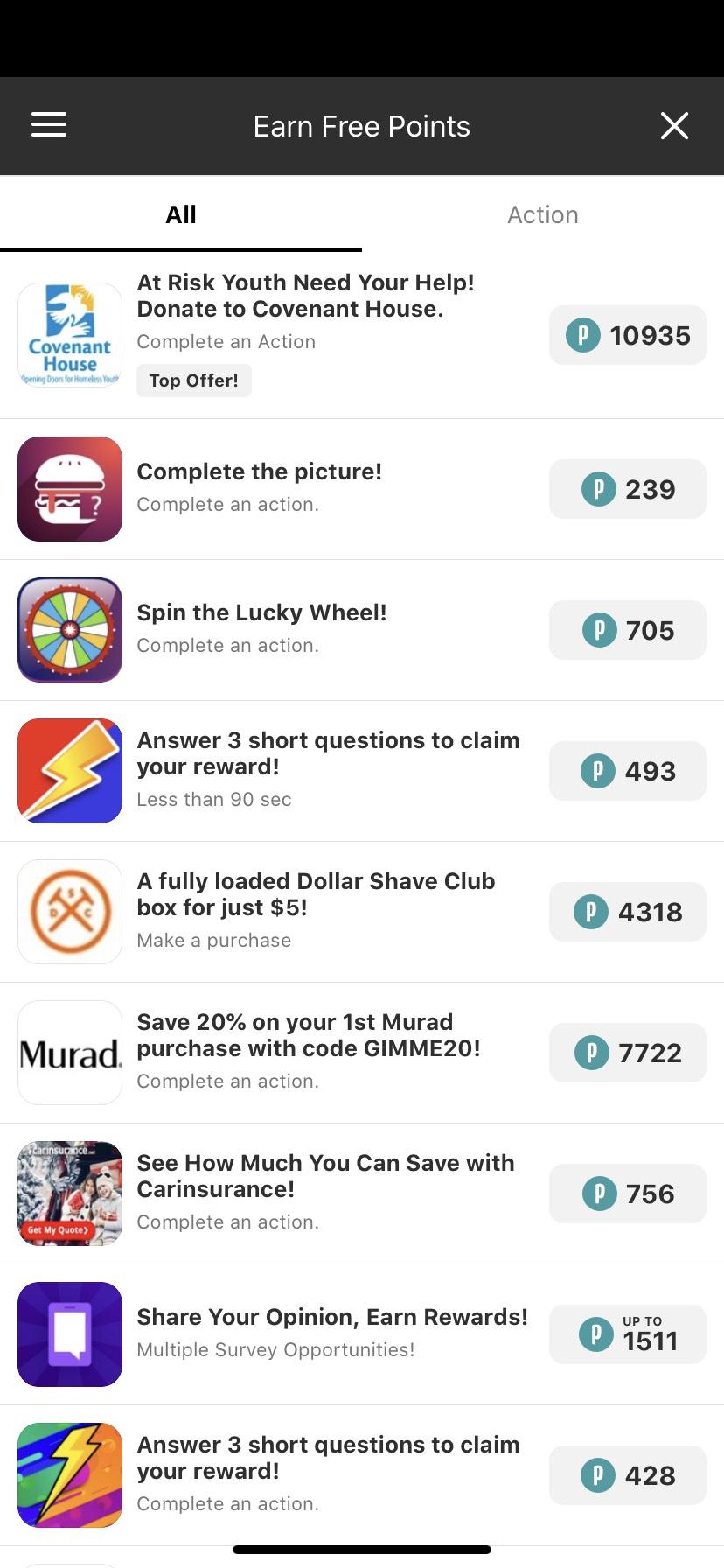

The offers, which promise more riches, are also unbelievably scammy looking. They all ask for you to complete an action, where you’ll receive far more than the 10 points per ad that you can get from simply watching the same Gardenscapes ad every 30 seconds while brushing your teeth.

Nothing about this system has ever drawn me in enough to investigate the rest of the content on the Tappytoon app, so I haven’t. I came to the application to read the sequel to King’s Maker, and I liked the original so much I was willing to just pay the creators properly. So I bought tokens. I had to open another comic for the first time today to even see how many points it costs to read (300) and since I would need to watch all 30 ads to read a single chapter, that seems like a currency system that is hilariously out of whack. If Lezhin is a shiny casino, dark and promising, Tappytoon is a video poker machine in a gas station.

This isn’t necessarily a critique of the overall system of WebToon apps. This is a monetization strategy like any other; there are applications I haven’t used that utilize subscription models, where you pay a flat fee every month and get access to most of the comics and novels on the application, for example. And while I don’t know the politics on the back end (there’s a very real language barrier there) this does seem like a model where the creators can actually get paid to create their work, which isn’t always the case with a lot of webcomics. There is an expectation when you’re a writer or creator on the Internet that your labor is free, and that it should be free, and this model makes it so that that labor is being paid for.

If the content wasn’t any good, if there wasn’t anything worth reading, then the reader would ultimately have no reason to stay. It’s where my casino analogy runs aground (unless, I suppose, you’re a poker aficionado). But the content on these applications is good. In Lezhin’s case, two of the WebToons I’ve found there rank among the best reads of my year. There are bad WebToons, of course (I’ve written about I Fell in Love with my Girlfriends Brother for Exploits) but the quality of the writing and the art you’ll find there is quite worth the tokens, coins, shells, or whatever other currency on the app of your choice. Pay your writers at all opportunities and try out new formats, no matter what weird microtransaction systems they’ve got guarding their gates.