Learning How to Share

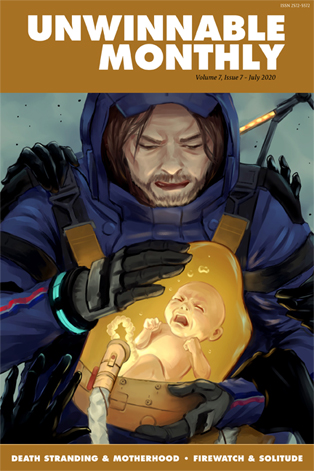

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #129. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #129. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Finding deeper meaning beneath the virtual surface

———

Though I’ve been blogging about games for some time, it wasn’t until about three years ago that I started getting published on gaming websites. When my writing began appearing at places like Paste, Waypoint, Unwinnable and ZAM, the public attention was often as intoxicating as it was panic inducing. Having not written anything professionally in the previous 15 years since leaving college, I felt deeply insecure about my ability to create something meant for public consumption, rather than for a patient college professor paid to educate me.

Some of this insecurity manifested in how I approached the in-progress drafts I sent to editors. Among writers, there’s a broad range of styles when it comes to handing in drafts. Some writers truly just treat them as drafts, vomiting their word salad onto the page, typos and all, for the editor to then piece together into something coherent. I’ve always been on the opposite end of the spectrum, especially so in the early stages of my career. Already plagued with impostor syndrome, I was afraid to show any cracks, any imperfections in the writing I submitted to editors. I never wanted to leave the impression of someone who was sloppy, who didn’t care.

So I wrote multiple drafts, and always triple-checked my work. And on many occasions, I would have my partner take a look, help me proofread and work out my arguments. She would also help me with pitches, help me coalesce the loose strands floating around my mind into a solid idea. At the time, I saw it as the kind of reciprocated generosity that close family and loved ones do for one another. Even though she wasn’t a professional writer, she completed a media studies major at school, and we’d done a bit of creative writing together in the past. So I respected her input, her eye and her clarity. And whenever it came time for her to write admissions essays or cover letters for her own career, I would readily volunteer to help edit them, to proofread and offer structural critique. It felt balanced, until it became very clear that it wasn’t.

After all, my writing was for the public, while hers was obligatory and institutional. I was also doing a lot more of it, in much greater volume. It wasn’t, in any way, an even exchange. And even if it had been, what harm would adjoining her name to mine truly have done? The right thing to do, clearly, would have been to have given her credit for her contributions. But I didn’t

After all, my writing was for the public, while hers was obligatory and institutional. I was also doing a lot more of it, in much greater volume. It wasn’t, in any way, an even exchange. And even if it had been, what harm would adjoining her name to mine truly have done? The right thing to do, clearly, would have been to have given her credit for her contributions. But I didn’t, and haven’t up until very recently.

My insecurity was a major one reason why. And w While it’s never gone away, it feels nowhere near as debilitating now as it did when I was new to writing. That same lack of confidence, which already had me second guessing the quality and professionalism of my work, also made me frightened to ask for things. I didn’t feel comfortable handing in essays to my editors with questions about structure or framing, let alone asking to add my partner’s name to pieces where she had helped with that very structure and framing. In many ways Admittedly I was also preventing my editors from doing their job by preemptively giving the task to my partner to do uncredited instead.

There was also a deeper reason why I didn’t fight to add my partner’s name to my essays. My main profession involves working in the field of motion graphics, where the vast majority of my output is made for a third party,  executed by a, sometimes immense, team of designers. No matter how large my role may be in the project, it’ll always be considered a team effort. Writing, on the other hand, feels more singular: I can put an essay out,

executed by a, sometimes immense, team of designers. No matter how large my role may be in the project, it’ll always be considered a team effort. Writing, on the other hand, feels more singular: I can put an essay out, and attach my name to it, and, in that way, feel a much stronger, more palpable sense of ownership over it. I didn’t realize how important being able to claim ownership over my work was to me, until I started writing for an audience. And I think I unconsciously resisted having to share my name, share my ownership, because I was so used to doing so in my day job.

But not wanting to share credit is, and forever will be, a bad look. It means I took my partner’s help for granted, while soaking up and jealously guarding the spotlight. This came to a head when I co-wrote a large essay with another writer (an idea with some merit but also wildly unpredictable results). Our first draft came back with a significant amount of notes. We had only a few days to implement them, and my co-writer was unavailable to help. In stepped my  partner, who helped me clean up and improve the essay, even rewriting whole sections to be clearer. Because I was worried about how it might look to my co-writer or our editor, I chose not to rock the boat and ask for her name to be added to the piece. She ultimately contributed more than my named co-writer did, and got no credit.

partner, who helped me clean up and improve the essay, even rewriting whole sections to be clearer. Because I was worried about how it might look to my co-writer or our editor, I chose not to rock the boat and ask for her name to be added to the piece. She ultimately contributed more than my named co-writer did, and got no credit.

We both recognized that a transgression had occurred, but my attempt to set things right wound up being rigid and unhelpful. I didn’t want my partner to  continue working on my essays uncredited, but I also didn’t want to share the credit. So I shut her out. I stopped asking her to proofread or even casually read my drafts, I stopped talking to her about pitches, about my ideas. I wanted to hold true to my sense of owning what I wrote, but that ownership came at the cost of excluding my talented, creative partner in a process which we had previously enjoyed sharing. All because I couldn’t conceive of a way to share without losing that ephemeral sense of pride and ownership.

continue working on my essays uncredited, but I also didn’t want to share the credit. So I shut her out. I stopped asking her to proofread or even casually read my drafts, I stopped talking to her about pitches, about my ideas. I wanted to hold true to my sense of owning what I wrote, but that ownership came at the cost of excluding my talented, creative partner in a process which we had previously enjoyed sharing. All because I couldn’t conceive of a way to share without losing that ephemeral sense of pride and ownership.

I still left avenues open to our potential collaboration, but they tended to be on my terms. I wanted us to follow a strictly defined notion of co-authorship: meaning we both play the game, jointly conceptualize a pitch, and finally write the whole piece together. I could see space for us as working a team, sharing the  load equally. But she had no interest in approaching writing in the same ways that I approached it. She didn’t enjoy critiquing games as much as she enjoyed working with me on the critiques that I was developing. She didn’t want to write about games as much as she wanted to help fine tune and finesse the writing that I was already doing. What we had before worked for her. She just wanted me to share the credit, the one thing I felt uncomfortable doing.

load equally. But she had no interest in approaching writing in the same ways that I approached it. She didn’t enjoy critiquing games as much as she enjoyed working with me on the critiques that I was developing. She didn’t want to write about games as much as she wanted to help fine tune and finesse the writing that I was already doing. What we had before worked for her. She just wanted me to share the credit, the one thing I felt uncomfortable doing.

This past July, for Bullet Points Monthly, I wrote a piece about The Last of Us 2. My partner and I spoke about the idea I had for it, as we took one of our daily walks around the neighborhood (our latest ritual since the pandemic hit). She helped me develop a larger, more unwieldy idea, into something more feasible to write and far easier to read. Since I’m an editor for Bullet Points, it didn’t feel like a particular hurdle to have my co-editor add her name below my bio, to credit her for consulting on the article’s idea. And when it went up . . . nothing happened, nothing blew up, no one called me a fraud, no one questioned my authorship or my participation, or my ability. After all the years of needless insecurity, nothing happened at all.

I write this essay not just as an apology for my selfish and misguided behavior, but also as an effort to challenge the kind of thinking that led to it. Sharing credit shouldn’t feel like sacrificing your reputation or taking away from what you have accomplished. E, especially when you are sharing it with someone close to you, someone with whom you already share so much of your life with. Why did I close off this part of myself, why did I hoard all the largely vacuous and immaterial attention my writing received, despite telling myself I wanted to share it with her as well? Insecurity, fear, and miscomprehension all contributed. Yet, but not seeing sharing of credit as the norm in online criticism also had an effect. If this piece does any good, perhaps it can be to push my peers to do better at crediting those around them who provide them with often much needed help in the difficult task of writing  and doing criticism, who deserve their flowers as well.

and doing criticism, who deserve their flowers as well.

———

Yussef Cole is a writer and visual artist from the Bronx, NY. His specialty is graphic design for television but he also enjoys thinking and writing about games.

Vivian Chan studied media studies in college and is a current psychiatry resident in NYC, where she resides with her partner and two cats.